Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

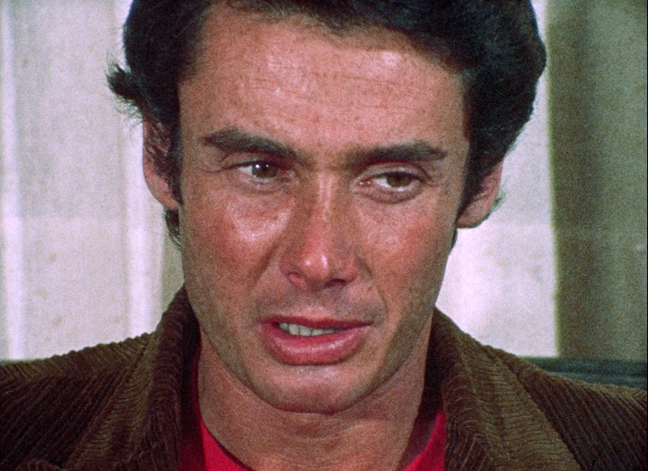

Michael Findlay was a young New Yorker, fascinated with film and the mechanics behind it.

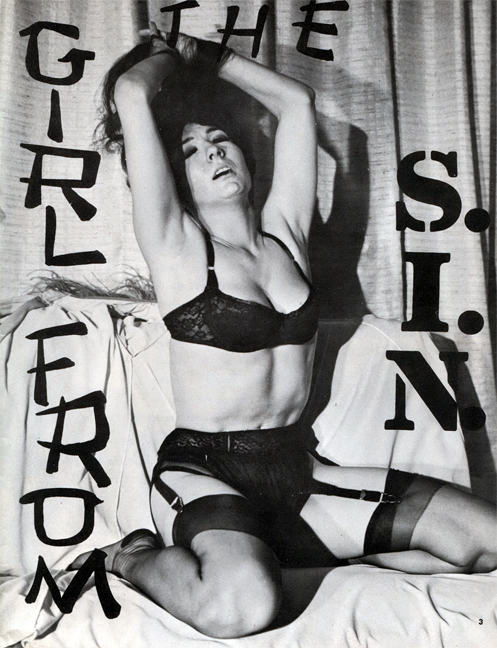

Julian Marsh was his alter ego, a movie director possessed with a singular twisted vision.

Richard Jennings was a sadistic, deranged movie character, one-eyed, confined to a wheelchair, and hell bent on revenge.

The films Michael Findlay made seemed to be so single-minded, unique, and personal, that they begged the question, how much were these three characters actually the same person? And what role did Roberta, Michael’s wife and partner, play in making the movies?

In the last episode, I spoke to Roberta to find out how her early life shaped her. Was there anything in her background that explained the Flesh trilogy, the black and white 1960s sex and sadism films that they made? I learned of her insular Jewish upbringing, a violent father, pressure to become a concert pianist, and an abusive relationship with a psychologist. Roberta minimized her actual involvement in the films, insisting that any role she had was somewhere between coincidental and non-existent, but questions remained.

So who was Michael Findlay? What shaped him, what was the damage in his past that Roberta referred to, what caused it, and how much of it resulted in the films that he made?

This podcast is 36 minutes long.

—————————————————————————

Someone once said that if you want to reveal the truth, you write fiction. But if you want to tell a lie, you write a biography.

So how do you start to tell someone’s story who you’ve never met and has been dead for almost fifty years? How do you get to know them, understand them, and get inside their aches, drives, and desires?

Start with the basic facts. Establish an overview of a life like a chalk outline of a dead body at a crime scene. A silhouette profile that establishes what is already known.

Michael Findlay was born in 1937 in New York. He made a number of notorious 1960s low-budget movies that combined sex and violence in imaginative and sadistic ways. And he died in 1977 when he was decapitated by a helicopter on the roof of the Pan Am Building in Manhattan – a grotesque end that could have come straight out of one of his films.

After the basic facts, dig deeper into echoes of the past. Chase memories, the architecture of our identity. After all, the life of the dead is placed in the memory of the living. So seek the survivors, anyone who guards recollections that may reveal deeper truths.

In Michael’s case, few people remain who knew him in his formative years, and some of those who still live choose to preserve their silence: many years have passed after all, and for them, the past is a silent setting, a place of reference not a place of residence.

But keep looking, ask enough people, and a story emerges.

*

Michael Findlay was born in Manhattan on August 27, 1937, just a short distance from Roberta, his future wife’s childhood home in the Bronx. In truth, it was a million miles away from her airless, bookish, piano-playing, indoor Jewish upbringing.

Michael was the product of a Celtic union: his father, James Findlay, was a Scot, a tall, good-looking bear of a man, born in Aberdeen in 1900, and product of the local, hard-scrabble shipbuilding yards on the cold, eastern coast of the land. Findlay senior, charming, outgoing, and popular, had little schooling but was keenly intelligent, a reader, and a collector of intellectual ephemera. Later in life, Roberta remembered him polishing off the daily New York Times crossword in under ten minutes, a source of amazement to her as she needed at least thirteen.

James spent his youth traveling the old country in his tartan, avoiding conscription to the Great War, taking hard labor temporary jobs, and dreaming of a better life. In his late teens he ventured over to Ireland, and, in the town of Kilkenny, he met and fell for Ellen Delahanty. Ellen was a strict Catholic girl from a strict Catholic family. The message to James was clear: any form of relationship with her was strictly off the table unless his intentions were serious, honorable, and permanent. James’ love for Ellen left him with no alternative, so in 1922, they were married.

Job opportunities for the newlyweds were scarce, both in Ireland and over the sea in England where “No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs” would become less a racist preference and more of point-blank threat. In the late 1920s, the young couple were tempted across the ocean to New York lured by the promise of a new life in the Empire City: their timing was dramatically imperfect – they were greeted by the 1929 stock market crash followed by the Great Depression – and James ended up a lowly janitor for a succession of Upper East Side apartment buildings for the rest of his life.

The Findlays settled in an uncomfortable co-op townhouse at the unfashionable end of East 65th St in Manhattan. It was rent-free because James was the building’s super, but the downside were the cramped rooms, barely bigger than closets. Compounding the chronic lack of space, Ellen then gave birth to three tall, strapping sons.

Just like Roberta’s family, the first two came in quick succession: the elder, James (who went the name ‘Bob’ to differentiate him from his father) and Gordon. Let’s cheat and fast forward a lifetime: they came from the same family as Michael, so what happened to them?

Bob, the eldest, is described as “the strangest, craziest member of the family, of any family” by one friend I spoke to. Bob would train as a priest, drop out and marry a quadriplegic, paralyzed in her arms and legs and confined to a wheelchair for life, and he then become the head of a notorious mental institution in Westbury, Long Island. Asked about the place he ran, he would crack, “The only thing that makes me different from the nuts in this place is that I sit behind a desk.” Today, as he approaches his 100th year, he lives in a nursing home. He is unsparingly friendly until asked to discuss Michael or re-visit his family’s early years.

Fast forward through another lifetime: Gordon, the middle brother, would become a brilliant chemist with an accomplished career ahead of him, but he died mysteriously while still in his forties. No one talked about Gordon after that, airbrushed from existence, and long forgotten in today’s world.

Which leaves Michael, born a few years after his brothers, a solitary, virtually only-child: “6’ 2” and still the smallest of the three,” says Roberta. “The runt of the Findlay family. Not my words,” she adds, “that’s what his own family called him.

“And he was damaged too. But whatever that damage was, it happened before we met.”

*

In truth, Roberta knows little about Michael’s early years. She never probed, he never volunteered, and their relationship was based on navigating the dangers of each day. After several months of chasing dead ends, I find someone who did know Michael. Roy is an aging ex-schoolfriend of his, and what’s more he says he remembers Michael well. So I call him, and we meet up.

Roy is a thoughtful, sober, and dignified man, a retired college lecturer in American history. It’s been decades since he stood in front of a class, and he’s frustrated that he’s lost the easy fluency of speech that once informed his classes. Today he speaks carefully and slowly but it’s clear that Roy still remembers Michael well. I complement him on his powers of recollection: “Memories remain crystal clear if you spend a lot of time dwelling on them,” he says.

But Michael died in 1977, I suggest. Why is he still on your mind?

Roy sighs. “I think of the past because most of my life is there. And Michael… he weighs heavily on my heart.”

Roy has brought a faded picture of Michael to show me. Michael as a teenager, looking twelve or thirteen going on 48. He’s wearing an old-man flannel suit that hangs redundantly off his apologetically tall frame. He has kind, self-conscious eyes and is smiling broadly, which surprises me. I realize I haven’t seen many pictures of Michael smiling. I ask Roy if that is how he remembers him?

“Mike was good company, sweet and gentle,” Roy says. “He was a happy-go-lucky kid and sunny, a big heart and a big laugh. He didn’t have a care in the world.

“For years, we were inseparable: we sat next to each other in school, walked home together, and played in the street. It was a typical New York upbringing: we opened fire hydrants on the street in the summer, climbed trees in the park in the fall, and made snowmen on street corners in the winter. Cliches, I know, but true. Sure, we got into trouble, but we were kids having fun.

Roy smiles: “In fact, we were arrested once: we lived near a pharmacy owned by an angry Ukrainian called Bohdan who had a prosthetic plastic arm. He’d lean on his countertop and this false arm would bend like a bow. That fascinated us, and we stared at it for ages. That’s what passed for our TikTok entertainment back in the day, I guess.

“Bohdan was also blind in one eye, and it was covered by a large, black pirate patch. Michael noticed that if you did something on his left side, Bohdan wouldn’t notice it on account of his partial blindness. So we took advantage and swapped around all the product in the store: we’d move the men’s hair pomade to the women’s perfume shelf and so on. One day, a cop saw us and hauled our asses down to the precinct. Michael took it all in his stride, enjoying the experience as if we were on a day trip to the beach. Afterwards, he said, “When you’re thrown in jail, a good friend will try to bail you out. But a best friend will be in the cell next to you saying, ‘Boy, that was fun!'” I think he stole that from the Marx brothers, but it made us laugh. Michael was funny like that. And all his eccentricities and quirks made him amusing and popular in our group of friends.”

I’m intrigued by the mention of eccentricities. I ask Roy if he knew much about what shaped Michael: “The church and his mother shaped him, I know that. We all saw the effect that they had on him.”

I press him: “His parents were sweet and kind. Everyone liked Michael’s father. His mother was fine too but she was religious. Man, was she religious. She was a fierce Irish Catholic. The family had a big portrait of the Pope in their apartment. It hung over their dinner table. She told the boys that the Pope was watching them all the time. Mike believed it too. It freaked him out. I remember him once or twice saying that he’d let the Pope down because of something he’d done.”

How did the religion affect his everyday life? “Ellen wanted all her sons to become priests. Michael’s brother, Gordon, wasn’t interested because he had his eye on being a scientist. But she persuaded the other two, Bob and Michael, that devoting their lives to God was their duty. An absolute duty. She talked about nothing else.”

How did Michael react to that?

“He accepted that the church would be his future. He wanted to please his mom and he did everything with a shaggy dog enthusiasm, happy and clumsy.”

So church was his life?

“Yes. It felt like the only time we were apart was when Michael was in church. My parents weren’t strict like his, so I went to church but not as often as Michael. He spent Sundays in church, Wednesday and Friday evenings in church, and then on other days, he had Bible class, catechism, choir, you name it. There was always something.

What was the family household like?

“They lived in a claustrophobic, cramped, and dark apartment. On top of that, his mother had a couple of sisters who came over from Ireland. They were nuns. And lesbians. Heavy drinkers too. One of them worked in an all-girls private school in Maryland. She always seemed to be drunk. They often stayed in the Findlay’s tiny apartment.

“We thought it was hilarious because they’d both chase Michael around and they’d terrorize him. They’d tell him he was bad and that the Pope was going to get him. He was scared of them, but he was also fascinated. It was the combination of their physical threat and their mysterious sexuality, I guess. He obsessed over them, not understanding how such holy people could act like that. Sometimes it got too much for him, and he was wary of going back to the family apartment.”

What did he do to escape?

“We hid out in the movie theaters. We got to know them all – as well as all the ticket sellers and ushers. They’d see us coming and smile. Even let us in free sometimes.

“That changed his life. He became obsessed with movies. Some days we’d skip school and see four or five different films in a single day. That wasn’t uncommon. The movie theater was our living room, our bedroom, our sanctuary.”

What kind of films did he like best? “Anything. High-brow, low-brow, Michael treated every film the same. He always chose which films we’d see. He’d go to the big theaters and see the Hollywood new releases, and the smaller theaters with the imported subtitled European films. He even went to the downtown movie houses in Chinatown where the films were in Mandarin.

“He had a memory like a database for those films. He read all the movie magazines. Every detail was stored away. I remember once going to see a movie with him that he’d already seen, and I noticed he was already repeating the dialogue back under his breath. He was almost autistic like that. Movies made him happy.

“So I’m thinking back to your original question: Yes, I remember Michael smiling a lot. That was Michael when he was a kid.”

*

It seemed to me that Michael’s childhood up to this point was reasonably typical of a kid growing up in Manhattan in the 1940s and 50s. Sure, there was the pressure to become a priest, an obsessive-compulsive interest in films, and a chaotic, crowded home to deal with, but his parents were caring and kind, he had close friends, and so was it really any more dysfunctional than many other kids in the city at the time?

And then I remember Roy’s comment when I first spoke to him: “Michael still weighs heavily on my heart.”

I email Roy again and ask him what he meant by that. He replies a few days later, and this time his words have a different tone.

“I don’t know how to tell you this,” he writes, “but I wasn’t entirely truthful the other day. That is, all of what I said was true. Our friendship. His family. The Catholic Church. The movies.”

Roy continues haltingly: “I’m going to write you a letter. I’ll explain there. I’d rather not discuss it on the phone. To be honest, I don’t much want to revisit it all. It’s not my story to tell. But your interest in Mike seems serious, and so I feel like you should know. You can disregard what I tell you or use it in any way you want. But after that, I don’t mean to cause offense, but we don’t need to speak again.”

I write back to Roy. I’m not sure I understand.

His response: “It’ll be in the letter. I’ll give you a couple of other names. You can speak to them. But that’s all I can do. I’m sorry. It’s been more painful remembering than I expected.” His words trail into silence.

*

After waiting for weeks, I begin to give up hope that I’ll hear from Roy again. Then his letter arrives.

He writes a polite opening. And then:

“Like I told you, I knew Michael from an early age. He was a happy kid and we were tight. That much is true. At least at the beginning.

“Then one day, Michael seemed subdued and sad. He seemed to have changed overnight. It was unlike him, and his dark mood continued for weeks. It was difficult to ignore, and, if anything, it got worse. It was like I’d lost my old friend. We were young, so I didn’t have the skills to talk to anyone about the transformation that I noticed in him. Eventually one night, I can’t remember where we were, I told him he was no fun anymore. I said he’d become silent and grumpy. I might have said he was boring too. I didn’t mean any harm, but he started to cry. I’d never seen that before. I immediately felt bad for raising it. I didn’t know what to say, so I didn’t say anything at all.

“Nothing changed. A while later, we’d made a date to go to the movies. I watched him walk down the street. I could see him arriving long before he got to me. He was tall for his age. And wiry thin. He wore ill-fitting clothes, probably hand-me-downs from his older brothers, and he appeared completely ill at ease with his lumbering teenage frame. He emanated a profound melancholy. It was like a spell had been cast on him.

“That night, we were sat in the park. He turned away from me so I couldn’t see his face. He started talking. He said that a few months before, he’d been away in upstate New York on a camp arranged by the church. He told me about a priest called T, who was one of the camp counselors. I knew T. He worked at the church we attended in New York. Michael said T started to be kind to him when he was at the camp. Extra kind. He took Michael aside and asked him about school, movies, everyday things like that, anything Michael was interested in. Michael said the priest found ways to be alone with him.

“After a few moments of being quiet, Michael just said he couldn’t understand how a priest, a man of God, someone who had taken sacred vows, would do that. He seemed lost in the moment.

“Michael didn’t say much else after that. He didn’t need to. Even though I was young, way too young to understand, I somehow knew what he was trying to tell me. I just knew. It made me feel uncomfortable. But I never did anything about it. Never told anyone. Never mentioned it to anyone. Never anything. I regret that. I still carry that regret with me all the time.

“After I became more distant from him. Not through my choice. Michael just pulled away. It seemed to me that now that I knew his secret, perhaps he saw me as part of the problem. He started to hang out with other boys. Boys that were older and did different things.

“We still went to see films though not as often as before – but now, the theaters were more than just a refuge from everyday life for him: they replaced his real life. The films we watched had gone from being his escape to become his reality.

“Michael still chose the films we watched, but they were different now. I still remember the movies he obsessed over like it was yesterday: ‘The Postman Always Rings Twice,’ where Michael lusted over Cora Smith’s bare midriff. ‘Red Dust’ where Cary Grant has a sexual affair with a prostitute, Jean Harlow. ‘Ball of Fire’ where Barbara Stanwyck plays a racy burlesque dancer. ‘Safe in Hell’ about a New Orleans hooker who kills the man who forced her into sex work and then fights off a group of lecherous escaped convicts. And instead of talking about the films afterwards, now he seemed embarrassed when they were over.

It wasn’t difficult to see what these films had in common. Michael had become obsessive about sex, and guilty about it too. It seemed to create a conflict inside him that he found hard to manage. It went beyond just a teenage compulsion. He seemed to be consumed with the fact that beautiful, promiscuous, and sexual women – prostitutes and strippers – were in front of him, yet out of his reach. Maybe it something to do with his commitment to the church, I don’t know.

“One moment sticks in my mind: I remember sitting with Michael and some friends in a soda shop. He was swaying in his seat, describing in forensic detail the contours and shape and texture and beauty of Lana Turner’s breasts as they pressed provocatively through her sweater. It was a tender though desperate description. He went on for ages, off in his own world, oblivious to anyone else, caught up the reverie of his lustful description. Everyone found it funny, but looking back, I feel uneasy.

“I only ever had one more conversation with him about what had happened at the camp: I asked him if he ever told his parents. He looked at me with horror. He said, No – he could never become a priest if they found out.

“I asked him if they ever suspected something was wrong? Michael said they’d started sending him to a therapist and prescribed him Valium.

“Why they do that if they didn’t know anything had happened? I wondered. He told me they’d found some of his notebooks in which he’d drawn and written about revenge fantasies. Sketches of guns, arrows, knives, poison, he said. After seeing the sketches, they decided he needed help.

“I told him I was sorry that this incident with the priest had caused such suffering in his life.

“Michael just looked at the ground, and said, “Who said it was just one incident? Who said it was just him?””

*

In 1952, when Michael turned 14, he succumbed to his mother’s wishes and applied to Cathedral College, a seminary at 557-559 West End Avenue on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. It was, as its president, the Very Reverend John Hartigan described, “a very adequate” place for “any boy of good character and intelligence who feels he has a vocation to the diocesan priesthood.”

To be accepted to the college, Michael had to take an examination and present a letter of recommendation from his local church pastor. Neither proved to be a problem, and he was admitted quickly.

The Cathedral College program was based around four years of high school education followed by two years of collegiate studies. Michael wasn’t the first of the Findlay boys to start training to be a priest: by this time, his brother Bob was already attending St. Joseph’s Seminary and College in Yonkers, sometimes referred to as Dunwoodie, and considered the Harvard of American seminaries.

And so, Michael took the first steps of his journey to be a man of the cloth. Each day, he walked across Central Park with a bag of books extolling the virtues of faith, dogma, and most of all, celibacy, the sacred vow of abstinence from all sexual activity.

*

Sal was one of the names that Roy had sent me, so I called him. Turns out he was an older kid that Michael hung out with after Roy faded from his life.

If Roy was serious and sober, every inch the former academic, Sal is all-action and bravado. He’s a livewire: a conversation with him is like a two-dollar trip on the Cyclone, the accident-waiting-to-happen, ancient Coney Island rollercoaster that still stands just down the road from where Sal lives today.

For a start, Sal is louder than a Brooklyn subway car. And hard of hearing too, shouting answers in upper case decibels. At times I wondered if it would be easier for me to open my window and listen to his voice across the city rooftops. He insists his memory is failing: “I’m so old, three things have happened. The first is my memory is shot, and… I can’t remember the other two.”

His daughter had warned me that he was a talker and nostalgic for a time that interested no one anymore. Sal agrees: “If I want to talk with my friends,” he shouts, “I head for the graveyard. I don’t drink to forget… after the life I’ve had, I don’t have the luxury of forgetting. But I do drink.”

“Anyway, you’re calling because of that Flesh movie, right?” Sal says. “I was the guy who drove into Michael with my car in that movie. The accident that caused his character to be paralyzed. That was me! I drove the car in the chase scene!”

I tell him that I had no idea he was involved in any of Michael’s movies – and that I’d love to hear about it. First though, I wonder if he could describe what Michael was like.

“Sure,” bellows Sal. “I was about 17 when we first met. I’m a couple of years older than him – a big deal at that age – but I called him ‘Old Man.’ He quickly became part of our group of guys. What was he like? Lovable, a sweetheart, sometimes a little intense and complicated. All at the same time. Despite his issues, everyone liked him. When I first knew him, he’d just started attending this Catholic seminary on the west side, so it was strange for us to have a wannabe priest in our group.

“Most of all, he was shy. Awkward socially and physically too. He had anxiety attacks. They paralyzed him.

What would trigger them?

“He was afraid of walking on the wrong side of the street, afraid of roaches, afraid of mirrors, afraid of a lot of things. He was more nervous than a long tail cat in a room full of rocking chairs.”

It turns out Sal loves a metaphor. How did he deal with his fears, I ask?

“I know his parents made him go to therapy, he told me that once – but I don’t know if it helped. But he didn’t drink, and took no drugs – unless you count the Valium which he popped all the time.”

I ask Sal if he had any theories as to what caused Michael to have these issues?

“It had to be the Catholics. They got inside his head, and he felt guilty for every bad thought he had. And we all had a lot of bad thoughts at that age!

“But he was funny too: Michael once told me his dad reached over and covered his eyes whenever there was a racy scene on TV… because his dad didn’t want Michael watching him masturbate. That was his humor: dry and full of self-defecation.”

Self-defecation? I suggest to Sal that he means ‘self-deprecation’?

“Yeah, that too,” Sal agrees, perhaps oblivious to the difference.

I ask Sal about Michael’s interests.

Sal barks back immediately: “Michael loved strippers, especially ones with big tits. Blaze Starr, Tempest Storm, all the burlesque queens. Michael adored those girls. He venerated them. He’d make us go anywhere to catch Blaze Starr. Atlantic City, Philly, DC. All over. And then he insisted on hanging around the stage door afterwards, even though he was usually too shy to speak to the girls. He once got Blaze Starr’s autograph and you should have seen his face: he was happier than a midget at a mini skirt convention.”

Where did you all hang out together?

“We liked Times Square because there was always some hustle going on. Michael loved films and so did we, so we were often at the theaters. But we liked to go downtown too. The East Village especially. It was seedy and raw down there. We hung out at places like Rapoport’s or Ratner’s Bake Shop.

“For his eighteenth birthday, we thought it would be funny to take Michael to Club 82. It was a basement nightclub on East Fourth Street, just off the Bowery, back when the Bowery was spikier than a badger’s butt. It was tiny place that was nothing from the outside, but inside… it was wild. It had three shows a night, and the performers were all transvestites, men dressed as women. On top of that, all the wait staff were women dressed as men in tuxes. Not that it was a gay place. The opposite, in fact: it catered solely to straight people. Celebrities loved it: Liz Taylor, Judy Garland, people like that. We only got in because we knew the owner’s daughter. The owner was Anna Genovese, who was married to Vito Genovese – one of the original mob bosses in New York.”

I ask if Mike knew about the place before he first went in?

“No! That was the point.

“It was a smart joint, so we borrowed a jacket and tie for him to wear. We got him inside and the show starts. One of the performers, a big, knockout flamboyant character, came over and sat on Michael’s lap. Michael looked both terrified and happier than a dog with two dicks. Then the performer raised Michael’s hand to her chest, and he obviously felt something there that wasn’t quite right. Suddenly it clicked. He was terrified, mortified, horrified. We thought it was funny, but I don’t think we spoke about the experience after that.”

I asked Sal if Michael had a girlfriend in his teenage years.

“No. I don’t think so. I would’ve known. He was never interested in the girls in his neighborhood. He spent his waking hours dreaming of Lana Turner, dancers, strippers, and hookers. They were his dreams.”

The line went quiet, and then Sal offered a final memory.

“You know, we all went to a whorehouse one evening. I don’t remember whose idea it was, but there we were, and suddenly we found ourselves going in. It was summertime, one of those sweltering New York nights. This place was down on the Lower East Side. A building with lots of rooms, each with bed and a little sink in the corner. I remember, you had to pay for the room and the soap in addition to paying for the woman. Well, we all paired off with the girls and went to different rooms. I finished pretty quickly, and so went outside to sit on the sidewalk. Michael was already there. He looked sad. I said “Old Man… are you ok?” He just shrugged. He said that nothing had happened. He’d given it his best shot, but it didn’t work. Something was broken with him, he said.

*

I thought of the teenage Michael, of the contradictions and confused life he was leading. By day, taking classes in theology, divinity, and spirituality, he prayed, preached, and praised, and took vows of abstinence and purity. By night, he enjoyed a different type of experience. He craved sexual images on the big screen, adored strippers and dancers, and went to a cross-dresser club and a whorehouse.

If life can only be lived forwards, it can only be understood backwards. I’d wanted to understand Michael through the memories of others. But old memories are masters of deceit. Stories fade, adjust, and conform to what we think we remember. What to make about what I had heard?

Is that part of Richard Jennings, his fictional serial killer anti-hero, in Bohdan, the angry one-eyed store owner, or in his quadriplegic sister-in-law confined to a wheelchair? What about the nights inhabited with voluptuous strippers, lesbian aunts, and beautiful cross-dressers, or how about the guilty conflict wrought by religion and sexual frustration? And what to make of the abuse, damage, and violent thoughts of revenge? Did these seeds grow into the themes of his films?

The troubled lives of Michael Findlay and Roberta Hershkowitz were about to collide. Their joint story is about to begin. They had endured difficult childhoods as misfits, abused and confused. Their future films would, in part, expiate their troubles and obsessions. Their work would be different from anything seen before. What effect did they have on each other?

Go to heaven for the climate if you must, but go to hell for the company.

*

*

Awesome Article Michael Findlay Keep Up Good Work

Thanks Jeff!

Last week’s article/podcast was breath-taking, and I was concerned with how any episode with Michael might compare… largely because Michael died without giving any proper interview.

Oh me of little faith… why did I ever doubt The Rialto Report, the finest source on film??

If anything, this Michael episode is more poetic, elegiac, and well-researched than even the Roberta episode.

The lengths you went to find out someone’s life who has long passed is amazing.

This is a quite amazing achievement.

We really appreciate that Valery!

Compliments compliments compliments, blah blah. I can’t add any more superlatives to the this or the first episode which are exceptionally good.

But I have a question: Sal mentioned that he was present on set for ‘Curse of Her Flesh’: can I assume that his further recollections will be part of a future episode of this series? It is amazing that you have uncovered additional crew members of these films that we made 55+ years ago.

And I have a comment: This should be a book. You are giving away a story that is so detailed and well-written that it would be better to make available to the world in book form.

These are minor points however. You rock and this is fantastic.

Was going to say it was Clark Gable was in Red Dust, but the error appears to be in Roy’s letter, not your story.

Thanks James!

It seems amazing that so many people are almost out of the door of life – and then you manage to tell their story. Without you doing this, history would be lost. Thank you for this.

Thank you Jack!

This series is surely your magnum opus: everything you do so well in one series.

Thanks Rob!

As an obsessive completist, I’ve been working my way through the entire podcast series since discovering it about 3 years ago. I’m now down to the last dozen.

This is the first multi- part series where I’ve left thinking, “I love this… but I just feel there’s more about the films themselves that should be covered.” I wanted another 3 episodes that went into each Flesh film and discussed what made them so iconic. Sure, the couple who made them were fascinating, but I wanted to know more about the making of the movies.

Small complaint, but I do hope at some point Leslie decides to go back and re-visit the films.

Who the fuck is “Leslie”?!

If you’re going to make a “minor complaint”, you may want to get the “major” issue of getting the presenter’s name right.

The title is “The Origin of the Flesh series”.

Which part leads you to thinking that the films will be covered?? This is an oral history of people’s lives.

What you are asking for is like complaining you wanted chocolate when you were given free steak.

I’m just blown away, once again. You’re doing such marvelous, important work.

Aww thanks Tim!

The part about the priest and molestation made me tear up I must admit. Griping reading tonight. Looking forward to how this story unfolds.

Superb journalism

Thanks Keith!

Thank you so much for this. Been a fan of the Findlays for a while now and it’s nice to learn so much from someone taking them seriously.

Thank you Robert!

Finally some new information about the Findlays because someone actually bothered to pick up the phone and do some research. I want LESS blogger opinions and MORE new facts. Hope the next Distrubpix releases take note and up their game!!

Thank you Conor!

Perfection.

Thanks Kai!

Will there be a part 3?

Without a doubt, thanks for asking. I thought I’d give people a rest from my voice for a few weeks though…

Superb narration & a great story. Part three ASAP, please…

The Rialto Report consistently produces some of the best podcasts on the internet. These past couple about the Findlay’s have been no exception.

I’d love to hear more episodes about the 60s sexploitation, roughies, stag films, and the scene that surrounded them. There’s precious little documentation of this era and no one who could do it better.

Keep up the great work!

Please continue this amazing saga.

Wow!

I sure hope that somewhere down the line there will be a Part Three!

MORE FINDLAY! PLEASE MORE FINDLAY!!!!

Thank you for this amazing report. I don’t think I’ll ever be able to watch the flesh trilogy the same way again. Knowing Michael’s background it all makes sense in a perverse way.