Harold Kovner. Supposedly the director of only two adult movies, both in the early 1970s. But was there more to his film career than that?

He had an enigmatic past that included tales of World War II heroics, German Expressionist cinema, RKO Pictures, Orson Welles, left-wing political activism, the legendary ballet choreographer George Balanchine, and much more – but who was the man behind the mystery?

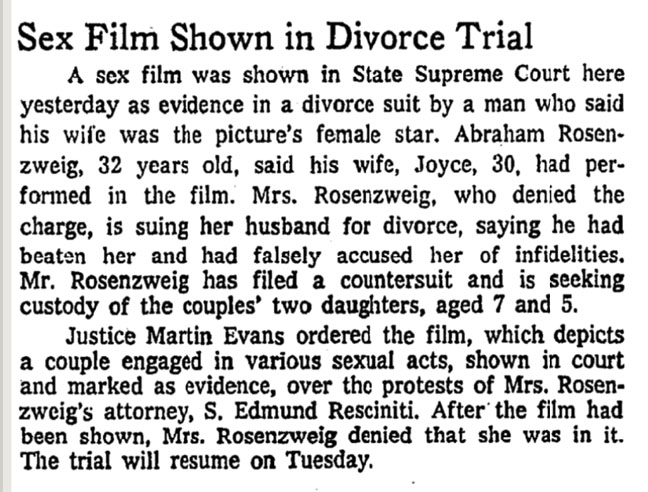

And how did he end up in New York Supreme Court as the key witness in a divorce case – in which a husband alleged that he’d gone to a Times Square grindhouse and noticed his wife on-screen having sex in an explicit pornographic film?

Harold Kovner’s story continues today, and includes 20th Century Fox, burlesque shows, Elizabeth Taylor’s husband Mike Todd, Roman Polanski’s movie producer, Andy Warhol, Sammy Davis Jr., Cosmos Films and the Capri Cinema – and the Greeks behind them both, money-laundering for the mob, as well as all the usual diversions, deep dives, and supporting characters that threaten to take over the story.

You can read Part 1 here.

The Rialto Report extends sincere thanks to the many family members, friends, and associates of those featured here for sharing their extensive memories and documents relating to this story over the course of many years. Thanks too to Joe Rubin of the inestimable Vinegar Syndrome.

—————————————————————————————————————————–

January 27, 1973 – New York Times

*

January 1973 – Harold

As requested, on Tuesday, Harold Kovner, audio engineer and self-described ‘Mr Rewind/Fast Forward’, went into court.

He saw her as soon as he entered the courtroom. ‘Jean Roman’ was sat quietly, elegantly dressed like a well-to-do suburban housewife. For a moment, he felt a pang of guilt that he was going to be the deciding factor in the whole case. He was the only one who could speak about the sex scene they had replayed on the courtroom screen. He was the one who would dismantle her passionate denial with a simple statement. And all because of what? An inconsequential sex film he’d made that he figured few would ever see? Harold later told friends that he felt sorry for the woman: he considered acting dumb and denying that he recognized her. But he didn’t want to cause trouble, so he sat patiently and awaited the judge’s instructions.

When his moment came, Harold took to the stand.

“You are going to be shown an excerpt of a motion picture,” began the judge. “We’re not here to judge you on your right to make a film that many might consider obscene. Your role is solely to confirm that this film was indeed produced by yourself, and that you recognize the women who features in it to be the same woman who appears in court today. Do you understand?”

“I do,” Harold replied, and the film began to roll.

*

1952 – Harold and Ely Landau

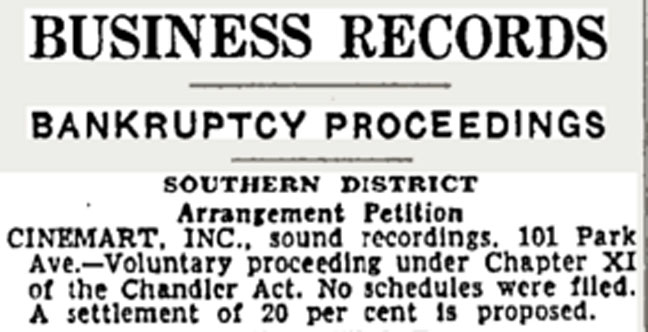

Cinemart’s demise had been a blow to Harold.

It was a company he’d formed with two of his closest friends, Varian Fry and Andre Carbe, with whom he was aligned on almost every level: artistically, commercially, and politically. Despite its failure, it’d been exciting to create something together, feeling as much like a social and support group as a new business start-up.

More than anything, the business had reinforced Harold’s interest in working in the motion picture business. Needing a fresh start, he teamed up with his old friend, Ely Landau, who Harold had tried to hire for Cinemart a few years earlier. Like Harold, Ely had served in the US Army during World War II, but since the end of the conflict, Ely’s primary interest had been television. So in 1952, he invited Harold to help start a new venture, Ely Landau Productions, which would produce low-budget TV programs. Harold accepted, but the business was short-lived as they soon realized that there was real money to be made not by producing new shows, but rather by exploiting movies from existing American film libraries and syndicating them to the big television networks. So they pivoted, and within a year of the launch, Ely Landau Productions was re-organized into a new company, National Telefilm Associates (NTA), with Ely becoming both President and Chairman, and Harold taking a role as a senior executive within the company.

The new venture was an instant success, with television stations eager to snap up film rights to show on their channels. By October 1956, Ely, Harold and the NTA board were flush with cash and decided to go one step further, launching the NTA Film Network. It was an ambitious big-time move: trade papers of the day referred to the new venture as the ‘fourth TV network’ – after NBC, CBS, and ABC.

The NTA Film Network immediately attracted over 100 affiliate stations, with its flagship station being WNTA-TV, Channel 13 in New York. Its syndicated programming included ‘Police Call’ (1955), ‘How to Marry a Millionaire’ (1957-1959), and ‘Man Without a Gun’ (1957-1959).

The company made waves and the majors sat up and took notice: in November of the same year, 20th Century Fox stepped in and purchased 50% of the NTA, announcing they would both exhibit their own films and produce original content for the new network. 20th Century Fox installed Ely as President of the company, and in 1957, Harold was appointed to the board of directors.

For Harold, it was the success that he’d spent his life seeking. He was now in the boardroom with heavy hitters from Fox, and mixing with power players from across the entertainment world. The sale to Fox also meant long-desired financial security for Harold: he had owned a minority paper stake in NTA Film Network, but his share of the Fox deal gave him equity in the new company.

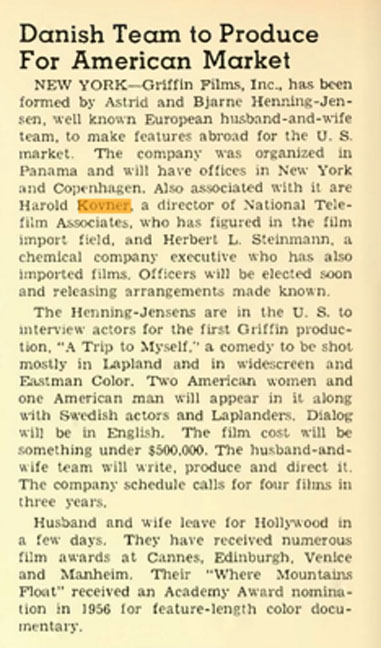

Life was good. He was close to Ely and the two vacationed with each other’s families. Harold was a surrogate uncle for Ely’s kids, including Landau’s son Jon. Crucially for Harold, outside of his NTA gig, he also had the independence to cut his own film deals – which he often did with highly-rated European filmmakers. Take Griffin Films, for example: in 1957, Harold teamed up with Herbert Steinmann, a chemical company executive who imported films, to assist two important Danish filmmakers, Copenhagen-based Astrid and Bjarne Henning-Jensen, forming the U.S. production company Griffin Films Inc. (Note for the curious: Steinmann’s son, Danny (aka ‘Danny Stone’), made one of the early landmarks of adult film: High Rise (1973)).

Or take Harold’s close friendship with Gene Gutowski who would go on to produce many of Roman Polanski’s films, including ‘Repulsion’ (1965), ‘Cul-de-Sac’ (1966), ‘The Fearless Vampire Killers’ (1967), and ‘The Pianist’ (2002). In 1959, Harold imported a controversial film, The Eighth Day of the Week, with Gutowski. Harold wasn’t just a high-powered film executive though: he also made socially-conscious documentary shorts. One of them, ‘Welcome to Bridgeport’ (1959), won several awards.

By the early 1960s however, there were clouds on the horizon for the NTA Film Network: despite the 50% ownership of 20th Century Fox, the business was struggling to develop into a major commercial television force on par with the ‘Big Three’ television networks. NTA’s flagship station, WNTA-TV, was losing money, so it was sold to the Educational Broadcasting Corporation, a forerunner of PBS. The sale proved to be a death knell for NTA Film Network: the company was dissolved in November 1961.

The end of the company hit Harold hard: one moment he had been high on the hog, living an expansive, luxury lifestyle. Within months, he was unemployed again, and the NTA Film Network shares he’d received were worthless.

He had to start over again. So in the early 1960s, he founded a new company, Motion Pictures Enterprises Inc., based in Tarrytown, NY, to develop film ideas. But funding for the new company soon dried up, and no films materialized.

*

Fast Forward – Ely Landau

As a result of Ely Landau’s initial stewardship, by the 1970s, National Telefilm Associates (NTA) had become the largest independent television distributor in the industry, acquiring various film libraries, including NBC Films and Republic Pictures. Ely eventually moved on, and became a successful film and television producer, with credits including Sidney Lumet’s ‘Long Day’s Journey Into Night’ (1962), John Frankenheimer’s ‘The Iceman Cometh’ (1973), and Arthur Hiller’s ‘The Man in the Glass Booth’ (1975). Many of his films explored themes influenced by his wartime experiences and the antisemitism he’d encountered.

Ely Landau’s son, Jon, born in 1960 and who Harold had been close to, also went on to a career as a film producer, winning Oscars and producing the likes of ‘Titanic’ (1997) and James Cameron’s ‘Avatar’ series (2009-2025) – three of the four highest-grossing films of all time.

Ely Landau died in 1993, and Jon died in 2024 after a long battle with cancer.

*

1967 – Harold and Al Baker Jr.

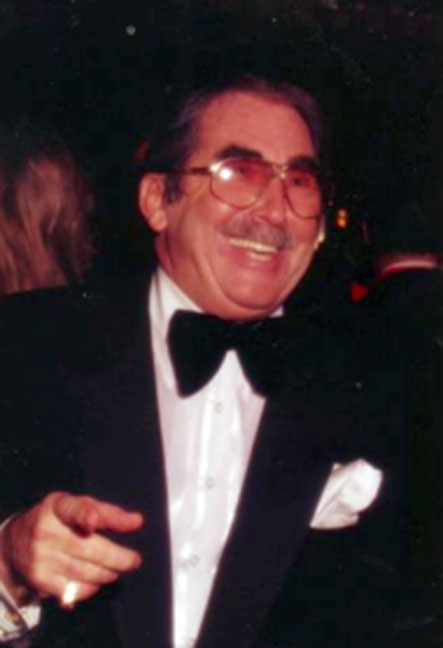

Al Baker Livingston, Jr. was a flashy, trashy man of many hats, but perhaps the greatest of his talents was his performative gift of gab. “Al could talk you into doing anything, anytime – and to anyone,” sighed one former associate. “He was the most persuasive person I ever met. And, believe me, that got a lot of people into a lot of trouble.”

Al Jr. liked to say that it was he who turned Harold Kovner into a pornographer – and he wasn’t completely wrong.

*

Rewind – Al Baker, Part 1

Al’s talent for performing was hardly surprising given his parents were both permanent staples on the burlesque circuit of the 1920s through the 1940s. Al’s father, Al Baker Sr., was a dark-haired sweet-talker who’d had a long career as a well-respected straight man to a series of comics. He worked the Hirst circuit, was beloved in the business, and made a decent living, occasionally supplementing his income by entering in dance marathons, sometimes dancing for two days straight without a rest to try and win cash prizes.

Al Jr.’s mother, Marcella, born in 1912, had been a young singer and dancer. But her career had been derailed at the age of twelve when she was injured in a car accident: “One foot got mangled under some metal, and her toes were twisted around where her heel should be,” remembered Al Jr. years later, “and it was set wrong so she never grew.” But Marcella hid it well, buying two differently sized shoes and becoming a ‘talking woman’ – a performer who acted as a banter partner with a comic in short sketches, often performing as a foil to the comedian’s jokes.

While on tour with her sister, Marcella met Al Sr. and they fell in love. Al Sr. would travel to various towns ahead of Marcella, book her a hotel, and leave a present in the room for her. After they married, Marcella became Al’s talking woman.

Al Jr. was born in 1934, and was raised on the burlesque circuit touring with his parents – an upbringing Al Jr. loved: “Everyone had a good time … and everybody was happy,” he said. “You traveled with twenty-two chorus girls, and we ate together, traveled together, as one big, extended family.”

Al Jr. grew up pampered, doted on, and spoiled. But he became a rough kid, often getting into scraps and trouble. When he told his father he wanted to study acting, Sr. responded, “You’re NT.”

“What’s NT?”

“No talent,” said Sr.

Sr. told his son he’d be better off learning to work the front of the house where the real money was.

In 1950, at age sixteen and hard to discipline, Al Jr. was thrown out of school and sent to a military academy while his parents continued on the road. It didn’t last long as Al Jr. ran away from the academy, so his father found him a job at the Grand Burlesque Theatre in St Louis. There Al Jr. met Leroy Griffith who was working concessions, figuring he could make more money selling candy, drinks, and trinkets than the performers in the show. The two got on well, and formed a friendship that would last for decades.

Al Jr. used his experience in St. Louis to parlay a trip to New York, sweet-talking his way into a job with theater and film producer, Mike Todd. It was a job that would change his life.

Todd had begun his career in the construction business as a contractor to Hollywood studios, soundproofing production stages during the transition from silent pictures to sound. His business failed and by the age of 21, Todd had already lost over $1 million (equivalent to about $20 million in today’s funds). His subsequent business career wasn’t much more successful, and his failed ventures left him bankrupt many times over.

Todd eventually became an impresario, owning theaters that provided dinner with live presentations and music – with a particular emphasis on burlesque. In Chicago in 1933, Todd produced an attraction called the ‘Flame Dance’ with gas jets designed to burn part of a dancer’s costume leaving her naked in appearance. The act attracted enough attention to bring an offer from the Casino de Paree nightclub in New York City. Todd grabbed the chance with both hands, moving to the Big Apple where he staged shows and found particular successes with musical comedy revues, typically featuring actresses in déshabillé, such as ‘As the Girls Go’ and ‘Michael Todd’s Peepshow.’

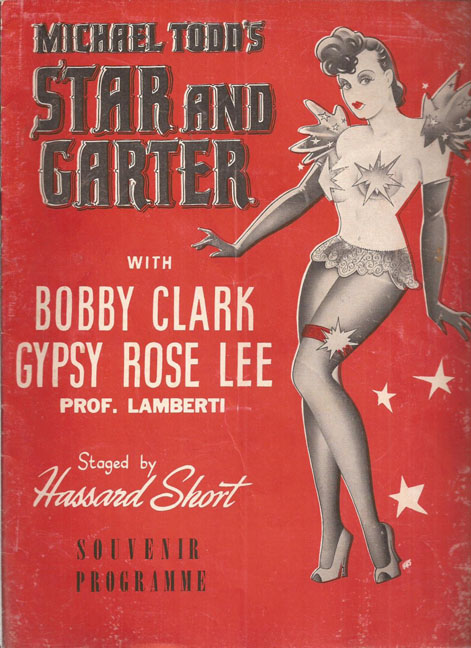

Al Jr. and Mike Todd became close friends and associates, despite the fact that Todd was almost thirty years older. Al Jr. became Todd’s right-hand man, and together they produced shows using women and men from the risqué burlesque circuit in legit Broadway shows in a bid to get around New York Mayor LaGuardia’s ban on burlesque. It worked – at least most of the time, as censors still gave them occasional problems.

Al Jr. worshipped Mike Todd and stuck close to him, learning Todd’s hard-earned lessons accumulated over the years. Al Jr. later credited Todd for teaching him everything he ever knew about running theaters and putting on shows. One lesson in particular stood out: “Todd always insisted on having his own name at the top of the bill… no matter who the star was,” Al Jr. remembered.

Mike Todd poster for Broadway show, with his name top of the bill

Mike Todd poster for Broadway show, with his name top of the bill

Todd ultimately produced 17 Broadway shows during his career – and Al Jr. was on hand to assist with many of them. The shows included the successful burlesque revue ‘Star and Garter’ starring Todd’s girlfriend at the time, Gypsy Rose Lee, and ‘The Naked Genius’ written by Gypsy Rose Lee and starring Todd’s next girlfriend, Joan Blondell.

Al Jr. soaked up the experience, and was grateful for the education, but by the time he got married and started a family, he’d become restless and impatient. He wanted to be his own boss, so decided it was time to go solo.

*

Fast Forward – Mike Todd

In the 1950s, Mike Todd pioneered a widescreen cinema operation called the Todd-AO process, designed by the American Optical Company. He first used it commercially for the successful film adaptation of ‘Oklahoma!’ (1955), before producing ‘Michael Todd’s Around the World in 80 Days’ (1956) – clearly still adhering to the principal of putting his own name at the top of the credits. The film cost $6 million to produce and grossed $33 million, winning the Best Picture Academy Award that year. Todd was suddenly the hottest personality in the entertainment world, in demand for film projects and by Hollywood’s most eligible starlets.

Mike Todd in 1957, winning an Academy Award, with Elizabeth Taylor

Mike Todd in 1957, winning an Academy Award, with Elizabeth Taylor

Todd had been married to actress Joan Blondell before she filed for divorce on the grounds of mental cruelty. His next marriage was even more tempestuous: in 1957, he got married to actress Elizabeth Taylor in Mexico.

In early 1958, Todd called Al Jr. and told him he was flying back to New York in his private jet to accept the New York Friars Club ‘Showman of the Year’ award. He wanted to meet up and have a reunion to remember the old days.

On March 22, 1958, Todd’s plane, the ‘Liz’, had been on its way to New York but crashed near Grants, New Mexico, killing Todd and three others on board. Elizabeth Taylor had wanted to go with him but had stayed home with a cold at Todd’s direction.

Mike Todd and Elizabeth Taylor

Mike Todd and Elizabeth Taylor

*

Rewind – Al Baker, Part 2

Al Jr. was in no doubt about the next chapter of his life: he wanted to own a theater and put on burlesque shows – and he was in no doubt where he was going to start his empire.

He’d always loved Atlantic City, New Jersey, from the first time he visited as a kid with his parent’s touring burlesque show. It reminded him of Vegas before Sin City had been fully exploited by every impresario, comedian, and stripper.

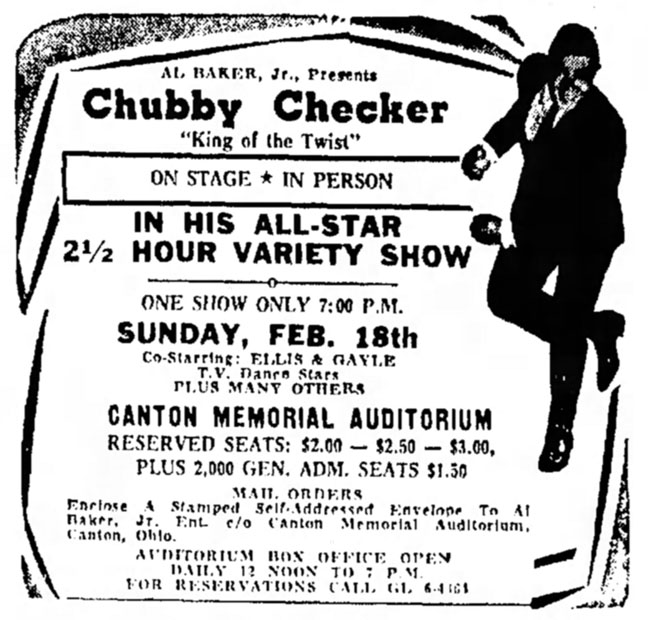

Al Jr’s first opportunity however came in Canton, Ohio in 1962, when was given the chance to put together shows at the Canton Memorial Auditorium.

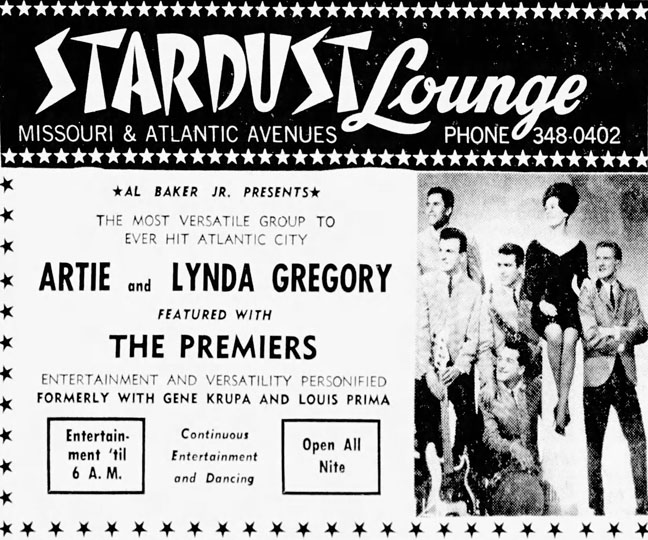

One of Al Baker Jr.’s earliest shows in February 1962, with his name at the top of the bill

One of Al Baker Jr.’s earliest shows in February 1962, with his name at the top of the bill

The events were well-received and made good money, so in 1963, Al Jr. finally moved to Atlantic City where he took over a sleepy jazz club called Schillig’s Escort. He remodeled the club and opened it as the Stardust Lounge, booking pop groups and filling it with a younger crowd. But within months, a fire swept through the building reducing it to rubble.

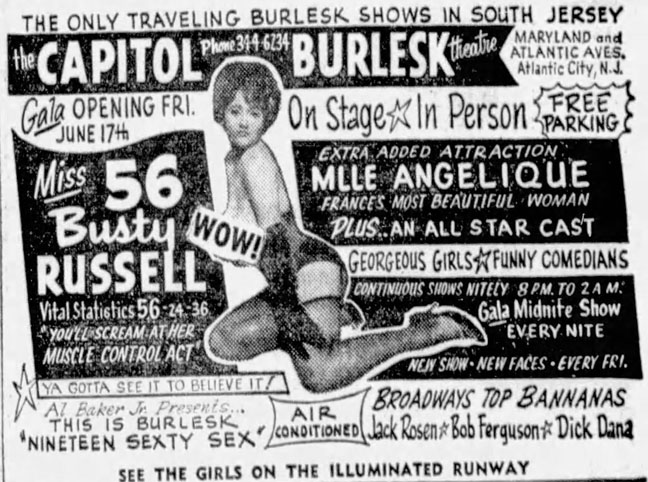

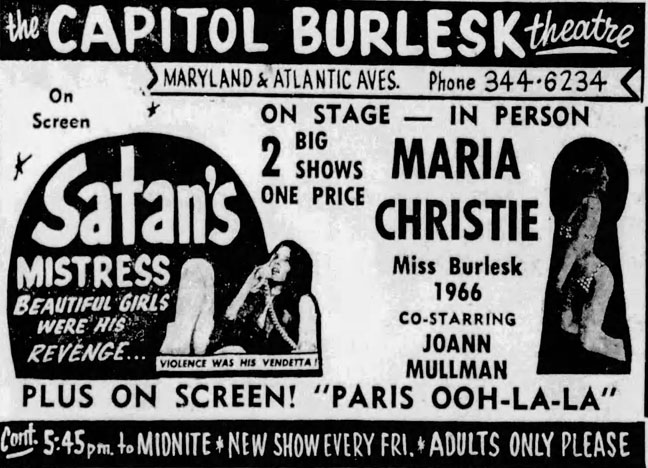

Some found the blaze suspicious, and their doubts were compounded when Al Jr. announced he was abandoning the idea of restoring the Stardust. He instead would use the insurance money to take over a bigger club, the Hialeah, at 1917 Atlantic Avenue. The re-launch of the Hialeah was a hit, but its real purpose was to pave the way for an even bigger project: in June 1966, after claiming in the newspapers to have spent $168,000 on refurbishments, he opened a new burlesque theater, the Capitol Burlesk, on Atlantic Avenue. There, Al Jr. staged nightly live shows called ‘This is Burlesk’ (with his own name above the title, of course), and kicked off the summer season with a performance starring the prodigiously-endowed Busty Russell, aka The Eighth Wonder of the World, aka America’s Dairy Queen. A succession of appearances from the country’s most notorious dancers followed, including Blaze Starr, a longtime friend of Al Jr.’s from the burlesque circuit days who appeared at the Capitol Burlesk in July 1966 as a favor to boost ticket sales. By the end of his first summer, Al Jr. capped his first season’s success by holding a much-publicized ‘Miss Burlesk of 1966’ show.

Opening night for Al Jr.’s Capitol Burlesk in Atlantic City

Opening night for Al Jr.’s Capitol Burlesk in Atlantic City

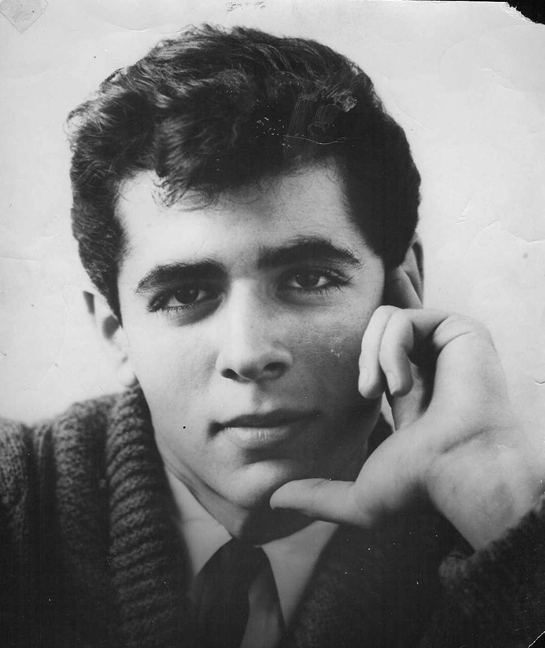

Al Jr. had finally made it big on his own – and what made him particularly proud was that he’d done it in the burlesque business. Around Atlantic City, he was a big shot, a celebrity known for his good looks, slicked-back dark hair, excessive gold jewelry, and his pink Buick.

His only problem was that running a burlesque theater in a seaside resort was a strictly seasonal affair, relying on summer vacationers who had surplus money to throw around. After Labor Day, when the holidaymakers disappeared back to their hometowns, the audience for big budget live shows decreased dramatically, leaving a theater owner needing a cheaper alternative to attract local ticket buyers.

Al Jr. had already prepared for the off-season, developing a solution with his old friend from the St. Louis theater concession business days, Leroy Griffith.

Griffith was several years ahead of Al Jr.: in 1961, he’d moved to Miami Beach where he bought the Paris Theater, staging burlesque shows, fighting off multiple legal challenges from city authorities who tried to shut the sex trade down, and then opening new venues throughout South Florida where he started exhibiting sex films.

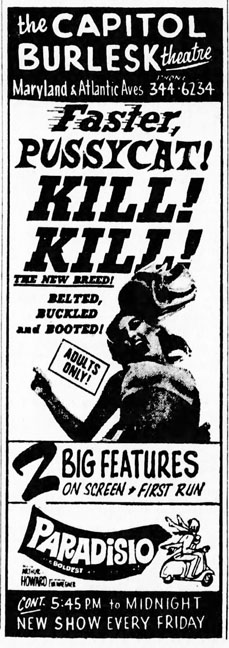

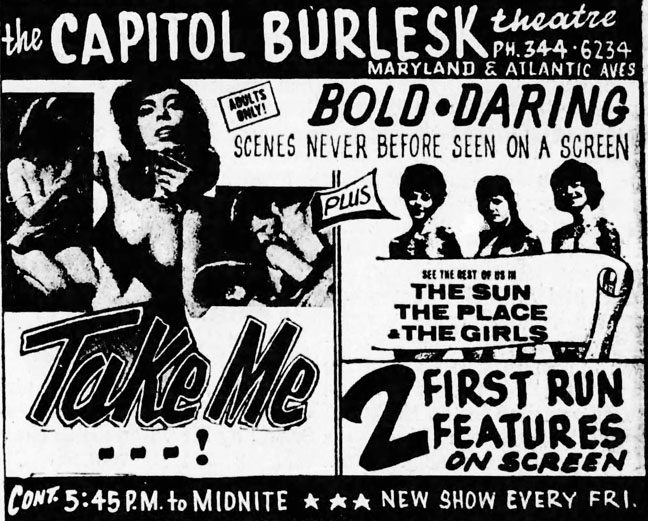

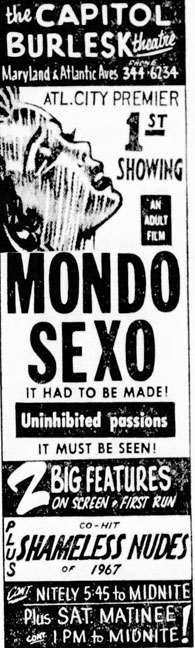

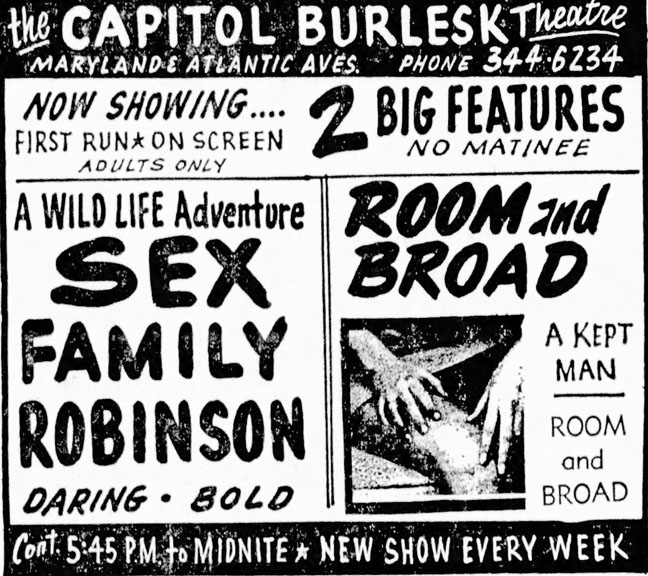

The films had provided him a cash cow, and Griffith recommended that Al Jr. do the same. Al took the advice and at end of summer season announced to the local newspapers that he’d show adult films in the theater, “two first run nudies weekly, with the new shows coming in each Friday”.

And so, for the eight months between Labor Day and the following year’s Memorial Day weekend, the Capitol Burlesk theater became a sex film palace (interestingly Al Jr. took his name off the posters for the film season… before restoring it for the burlesque shows). The movies ranged from Russ Meyer’s hits to the latest salacious efforts by the Findlays, the Olga trilogy, and more.

Selection of movies exhibited at the Capitol Burlesk:

*

1967 – Harold and Al Baker Jr.

Al Jr. started making regular trips to New York in his Buick, a two-hour drive from Atlantic City. Ostensibly the reason was to build relations with film distributors to secure a steady supply of sex films to exhibit at his Capitol Burlesk theater. But Al Jr. harbored greater ambitions: he dreamed of opening a New York theater that would recapture the glory days of burlesque. Not just that but, following Leroy Griffith’s example, he also fancied becoming a movie producer, even announcing his intentions in the Atlantic City newspapers, saying that he was “negotiating with agents in New York City for the star and director.” Griffith had been making sex films to show in his theaters since 1963, starting with the nudist camp movie Bell, Bare and Beautiful, starring burlesque queen Virginia Bell and directed in four days by future gore specialist, Herschell Gordon Lewis.

Al Jr.’s search for a someone who could direct his film projects led him to the door of Harold Kovner. Harold was still licking his wounds from the collapse of the NTA Film Network, and had been taking freelance film and television work – often industrials or commercials.

When Al Jr. turned up, they hit it off, even though they were an unusual combination: Harold, a serious, diligent film industry man, a socialist trying to thrive in a capitalist world; and Al Jr., a showy, flamboyant impresario and ambitious showbiz huckster. Friends remember that they found each other amusing, a yin and yang contrast in styles and substance, but somehow their relationship was complementary not contradictory, and they locked in on each other for business opportunities they could jointly pursue.

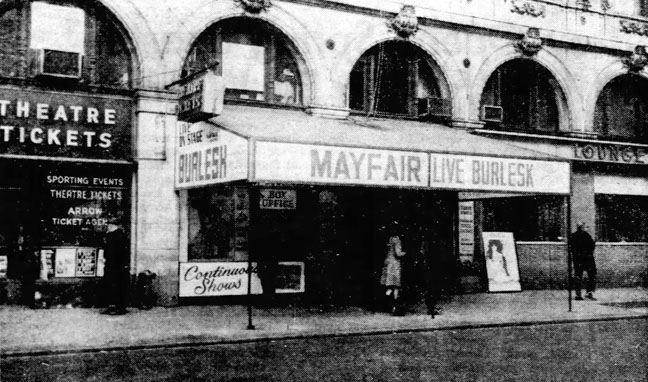

In 1967, Griffith called Al Jr. with an opportunity in New York. Griffith had been operating a burlesque theater in Manhattan in the basement of the Paramount Hotel at 235 West 46th Street (today the site of the Sony Hall concert venue.) The joint had begun life in 1938 as Billy Rose’s Diamond Horseshoe nightclub before becoming the Mayfair Theater in 1961, whereupon it featured a range of shows from burlesque to Yiddish theater to Broadway musicals. Griffith had taken over the lease in 1966 but struggled with the hands-on requirements of the burlesque business. He turned to Al Jr., offering him the lease and the chance to operate a prestigious location in the heart of the Times Square area.

Al Jr. jumped at the chance. It was an opportunity to replicate the success he was having in Atlantic City: strippers, comedians, and adult films. The deal would stretch him financially however, so he needed a partner. He turned to Harold, who had some savings from his freelance work but little free time. Harold signed up on condition that he would be a silent partner in the theater – with a financial stake but no day-to-day operational responsibilities.

In early 1968, Al Jr. and Harold opened the new Mayfair Theater with a daily program of “porns and strips” as Al Jr. described it. They paid Blaze Starr $2,000 for a week’s engagement: “She was nice with me. She demanded even bigger money for other theaters,” Al Jr. told reporters. Another of their strippers was Zsa Zsa Chesty Gabor, later known as adult sex film star Chesty Morgan, she of the 73-inch chest. As always, Al Baker’s name was at the top of the bill every week.

Al Jr. took an office upstairs in the Mayfair Theater and Harold stopped by most days, the two partners entertaining strippers and journalists alike. The new establishment attracted media attention, with one writer describing Al Jr. as “a wannabe Mike Todd, lean, dark-haired, wearing black-rimmed glasses and smoking Salems in a white cigarette holder.”

Business was good, Al Jr. told the press. There were occasional problems – such as when Al Jr. tried to introduce ‘Psychedelic Burlesque,’ a combination of 1960s acid-trip rock music with old-school stripping, and the girls protested the body make-up they had to wear – but it was all part of the day-to-day rigors of running a theater.

The Mayfair also attracted celebrity customers of different stripes: from boxers after the fight cards at Madison Square Garden to actors in town to shoot their latest flicks. Al Jr.’s friends from the burlesque scene often stopped by as well – including Sammy Davis Jr. One afternoon, Andy Warhol turned up with a pretty boy in tow, a kid by the name of Eric Emerson, and jokingly asked if they had opportunities for such an androgynous creature. Warhol quizzed Al Jr. and Howard on the strip shows, and was intrigued by how each girl created a different identity for herself. He commented that the women were like wrestlers, each with a unique personality hook that they’d exploit for a fan group. After the meeting, Emerson was a frequent return visitor to the Mayfair, often bringing a coterie of Warhol factory superstars with him.

As time went on, both Harold and Al Jr. talked more about making a movie together, and in late 1968, their opportunity arose.

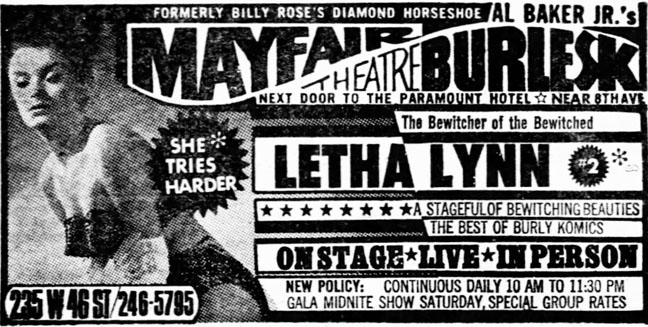

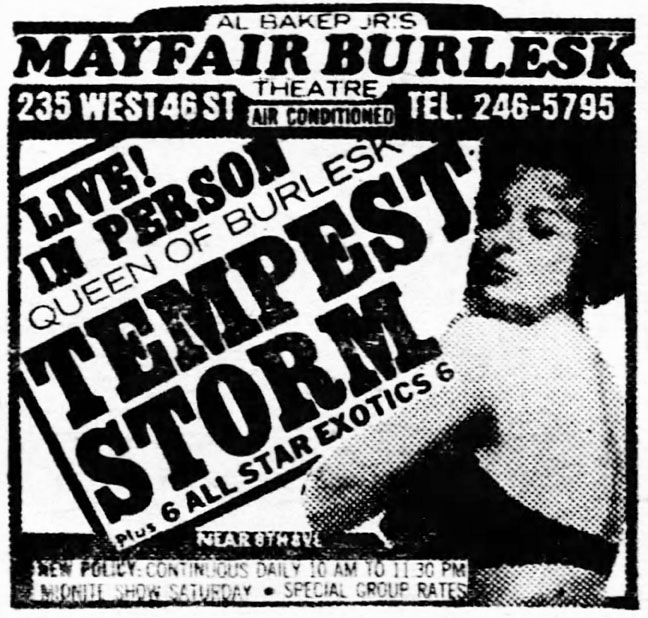

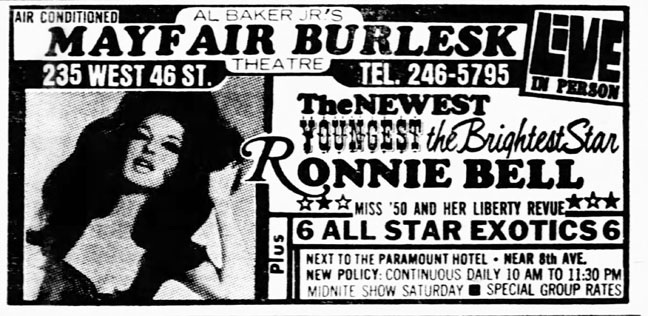

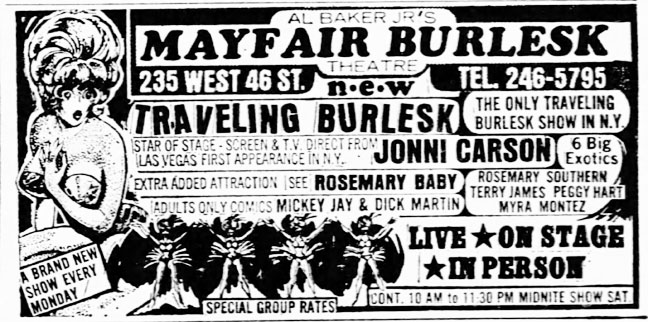

Selection of acts at the Mayfair Theater Burlesk:

*

1968 – Harold and the Greeks

Quite how Harold and Al Jr. first met the Greeks is perhaps lost to history. What is known is that in 1968, they came together for a productive partnership.

Tom Gioulos and Teddy Kariofilis were Greek businessmen, newcomers to the film business, with big ambitions to earn money they could send back home to Greece – and, allegedly, even bigger promises of mob-related financial backing. Together Tom and Teddy wanted to produce a series of softcore adult movies, and formed Cosmos Films for that purpose. When Harold met the duo, he figured that Cosmos, the company name, symbolized the stars in the sky but then Tom sat him down and explained: in Greek mythology, Cosmos represented the ordered universe that emerged from the void of Chaos. Their company was going to bring professionalism into the wild, unstructured business of dirty films.

Tom and Teddy had started Cosmos by agreeing to a two-picture deal with two semi-experienced producers, Paul Leonardi and Phil Todaro, whose company Leo-Tod Pictures had already made films with established filmmakers, such as Joe Sarno. Their first film collaboration for Cosmos, Hot Erotic Dreams had just been released in October 1968 – in the incongruous location of Waco, Texas, specifically the Capri Studio Adult Art Film Theatre there – and now the Greeks were looking at their next options.

Opening night for ‘Hot Erotic Dreams’

Opening night for ‘Hot Erotic Dreams’

Harold pitched them a script he’d written, ‘The Mind Blowers,’ and told the Greeks he could do it all single-handed – directing, shooting, and editing. Al Jr. chipped in that he would manage the whole production as well as supplying the female talent – taken directly from the pool of strippers at the Mayfair. When the Greeks suggested a budget of $15,000, $5,000 more than Harold and Al Jr. had hoped for, they signed up immediately.

The Mind Blowers (1968) was typical sexploitation fare for the time. Harold had been to see a few films in the local grindhouses, and aped their conventions. His film told the story of Professor Gotterdam who captured the sexual fantasies of his subjects by recording their brain waves. Trouble ensued when his assistant mixed up the tapes which caused the subjects to experience different fantasies. Ho hum.

The 35mm black-and-white movie was shot in three days at the end of 1968, and featured Eric Emerson, the Warhol protégé who’d become a regular at the Mayfair burlesque shows. It was nothing special – decent perhaps considering the speed of the production, but that hardly mattered to Harold. He trousered several thousand dollars for his efforts. If it seemed strange to him that he was making a softcore porn flick less than ten years after he’d been a senior executive on the board of a 20th Century Fox subsidiary, he wasn’t complaining. He reversed his surname into a directorial credit of ‘Harlan Renvok’ and provided the cinematography and editing using the name ‘Hal Jay’ (whether the film’s listed producer, ‘Guy King,’ was, in fact, Al Jr. is not known, though actors interviewed for this article remember Al’s presence on the set). The Greeks liked the finished product, and they especially liked Harold – though some reports suggest they were less keen on Al Jr.

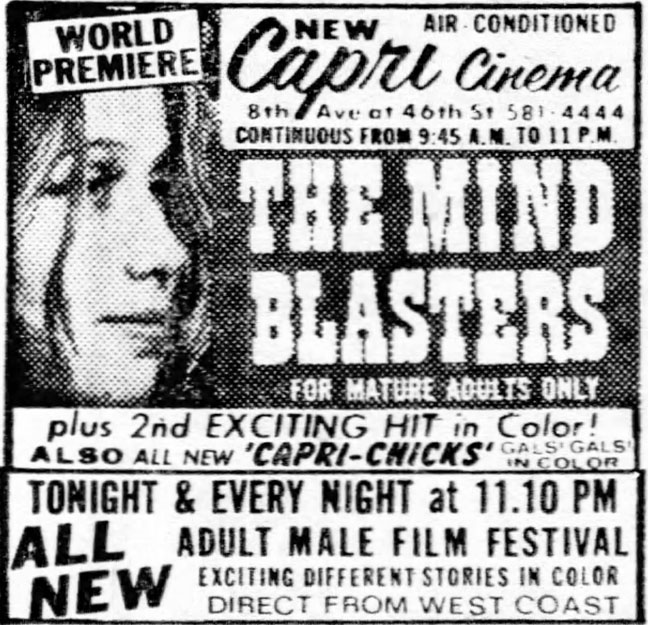

By the time ‘The Mind Blowers’ was ready for release in mid 1969, the Greeks had announced another major development in their film operations: Teddy (with Tom as minority partner) was launching the Capri Cinema on 8th Avenue at 46th Street, which would exhibit Cosmos’ own (and other company’s) sexploitation films. The grand opening took place on May 30th 1969 featuring Zoltan G. Spencer’s Tropic of Scorpio (1968). A few weeks later on June 24th, it was replaced with the ‘World Premiere’ of Harold’s ‘The Mind Blowers’, bowdlerized as ‘The Mind Blasters.’ It successfully played at the theater for a month.

Gala opening night at the Capri Cinema, 1969

Gala opening night at the Capri Cinema, 1969

Premiere of ‘The Mind Blowers’, 1969

Premiere of ‘The Mind Blowers’, 1969

The opening of the Capri Cinema had created a greater demand for Cosmos product, and in the wake of their successful collaboration, the Greeks approached Harold with a new offer: they wanted to finance a series of new Cosmos films to exhibit at the Capri. They had a few stipulations: the movies should be 16mm, color, softcore features, each with a limited narrative, and all were to be shot in California. Each film was to cost less than $10,000. Harold would get a flat fee and could also keep the change from the budget. Harold wasn’t one to ask questions, but figured the reason for shooting the films on the west coast was that California productions had become more explicit than their grim but tamer monochrome east coast counterparts: west coast filmmakers had incorporated elements from the so-called explicit ‘split beaver’ shorts, such as full male nudity and women with legs spread. For once, Harold didn’t have much else on his plate to occupy him, and as these films required minimal time and effort, he signed up to being an in-house director for Cosmos.

Over the course of 1969 and 1970, Cosmos produced at least twelve west coast sex films. They were released with virtually no credits so it is difficult to know how many were directed by Harold, but actors interviewed in recent years remember Harold directing several of them. Gerard Broulard, a semi-regular in these productions, remembered a barrel-chested New York director called ‘Harold’ or ‘Howard’ who flew in for a week at a time to make a batch of films, and doing most of the production work himself. Gerard recalled several of the titles being filmed back-to-back, with as many as four films being shot in four days, and with largely the same casts. Gerard’s partner Kathie Hilton appeared in even more of the Cosmos films, remembering that the “New York guy” was “friendly but no-nonsense and all-business” and that he chose actors who could be relied on to improvise a simple set-up for each scene. Gerard concurred, and remembered Harold liked to work with softcore veteran John Dullaghan.

To say the resulting films are largely unexceptional would be an understatement: most of the them were simple affairs, based on a single concept around which a series of sexual encounters take place. The camera work consists of long continuous takes leaving little need for editing.

Most of the west coast Cosmos output premiered at Teddy’s Capri Cinema: Dr Shrink (shown at the Capri in February 1970), Fisherman’s Luck and Runaround (both in March 1970), The Line is Busy and Ego Trip (shown as ‘On a Trip’) (both in May 1970), The Contest (in June 1970), Carnal Knowledge (exhibited as ‘A Time for Knowledge’ in July 1970), College Corruption (as ‘College Morals’ in August 1970), Caged Woman (in September 1970), and Love Me or Leave Me (in October 1970).

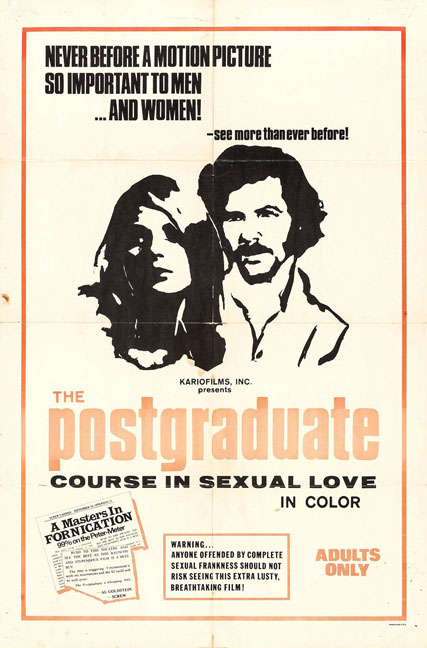

One of Harold’s California films does stand out from the pack – and it was the first film where Harold used his name on the credits: Post Graduate Course in Sexual Love (1970). The film was produced and distributed by Kariofilms, an offshoot of Cosmos, and follows the well-trodden white-coater trope of a professor (John Dullaghan again) in a sex-education class giving his students a lecture on sexual practices, which are then demonstrated on screen.

John Dullaghan in Post Graduate Course in Sexual Love (1970)

The film is more accomplished than similar movies of the era, and a step above other Cosmos fare, featuring better camerawork and an original score. According to the credits, ‘Jay Campbell‘ was involved in the production (having credits for writing it with Harold, and also for editing and sound), and the film is attributed to Harold’s company ‘HalJay’, presumably a partnership between Harold and Campbell. The identity of Jay Campbell remains a mystery, and no one contacted during research had any memories of him.

‘Postgraduate’ opened in New York at the Cameo Art Theater in August 1970.

*

1971 – Harold and Al Baker Jr.

In theory, Al Baker Jr.’s aspirations were similar to the Greeks’ – he owned theaters where he could exhibit his own films. The problem was that Al Jr.’s theaters – the Mayfair in New York and the Capitol in Atlantic City – were primarily burlesque houses, and Al still didn’t have any films of his own. An additional problem was that the Mayfair was losing money, and Harold was becoming itchy to get his investment back.

Part of the issue was that Al Jr. had spread himself thinly across his various theaters – and refused to hire sufficient staff to manage them. In September 1968, he bought the Troc Burlesk Theatre in Philadelphia – a sizeable venue with 450 seats – and sunk an investment of $40,000 into its renovation. Then he bought another theater in Toledo, Ohio. Harold and Al Jr. remained close but together decided to shed the Mayfair, and from mid 1969, all advertising ceased to mention Al Jr. and the pair’s active involvement in the theater ceased.

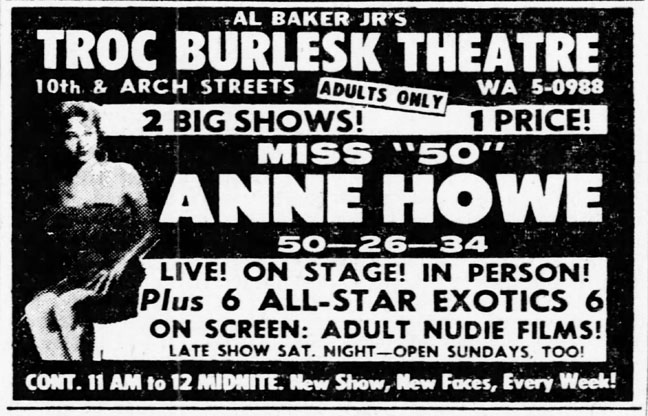

Al Baker show at his Troc Burlesk Theatre, 1969

Al Baker show at his Troc Burlesk Theatre, 1969

Harold had used the money from the Cosmos movies to set up a film studio and apartment for himself in the Tribeca area of downtown Manhattan at 76 Franklin St – which he named Hol-Jay Studios with reference to the mysterious Jay Campbell. Harold envisaged reviving his movie production business, but was also keen to return to his earliest love, and find work as a sound engineer. Following the success of the west coast adult films, Harold also started shooting 8mm sex loops: it was a new business for him – black and white, 8-10 minute long, soundless shorts consisting of wall-to-wall hardcore sex, shot in batches of six over the course of a single day – and he sold to a Times Square bookstore contact provided by Teddy and Tom. Some of loops featured future adult stars, such as Tina and Jason Russell, and Harry Reems. Decades later, in an interview with The Rialto Report, Reems remembered working with Harold in the downtown studio. Harold had little interest in artistry, Reems said, his main focus being on routine professionalism.

Occasionally Al Jr. was present when the loops were shot. He still harbored aspirations of making feature films and, in 1971, with the encouragement of Harold, he finally set up his own production company. His intention was to imitate the Cosmos model, shooting the features in California before exhibiting them back on the east coast – so he named his new venture Cross Country Films. Al Jr. had returned to living in Atlantic City, and set up offices at 2430 Atlantic Avenue.

Al Jr. ran Cross Country Films with an associate, J. Royce Adams – Al Jr. was president, Adams was VP/secretary. Adams was the owner of Royce Adams Enterprises, a film company based in Florida but which operated largely in theaters in upstate New York.

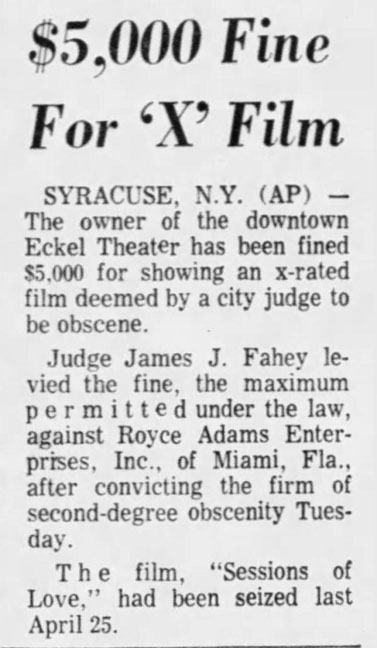

Royce Adams had a colorful and largely undocumented life. In 1965, as manager of Civic Follies Theater in Syracuse, he was busted for a film that documented the marriage of two lesbians – as well as for carrying a .32 caliber pistol. After advertising in Miami for scripts for movies (“Underground material also accepted”), in 1970 he premiered a counter-cultural documentary, It’s A Revolution Mother, which premiered at his own Capri Art Theater.

In 1970, Adams purchased a theater in Syracuse for $140,000 and spent $60,000 to renovate it, but efforts to expand his movie empire were thwarted when he was refused a theater license due to his history in exhibiting skin films. To make matters worse, he was prohibited from showing the scandalous stage show ‘Oh Calcutta’ via close circuit at his Civic Follies theater. Adams would go on to face multiple obscenity charges over the next few years.

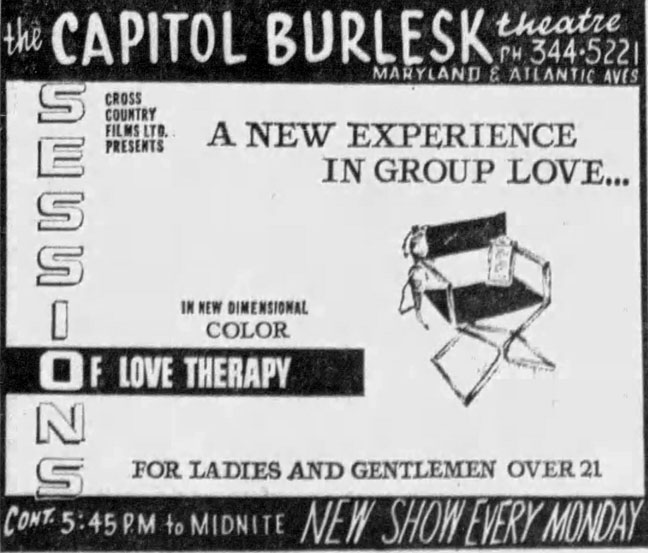

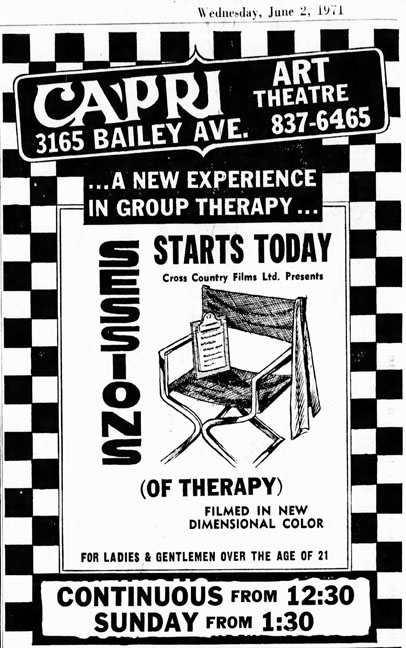

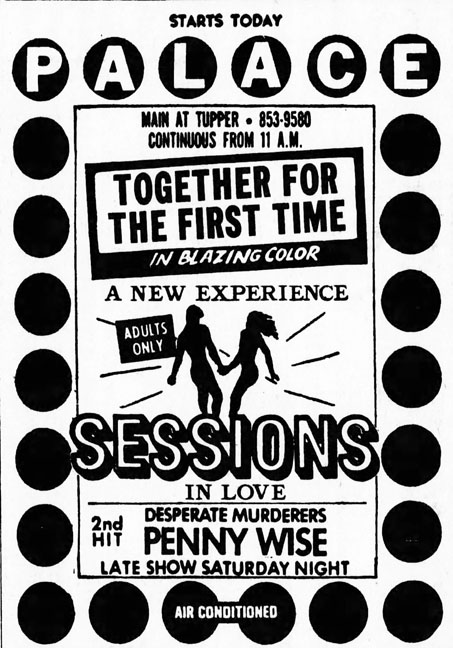

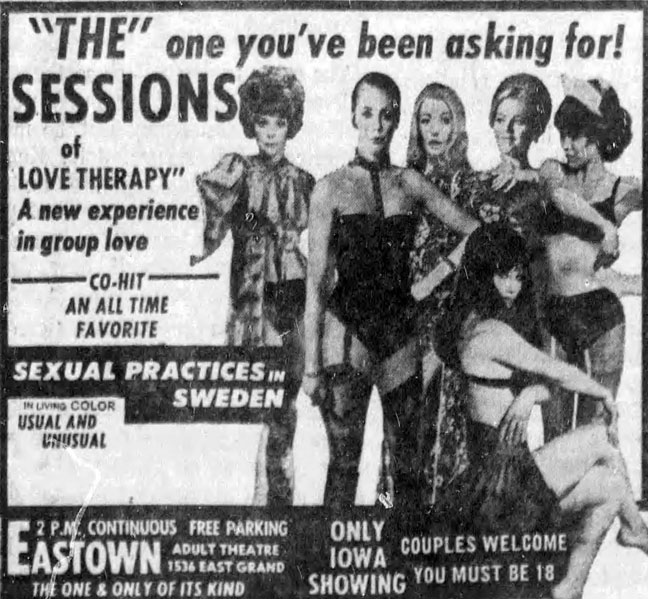

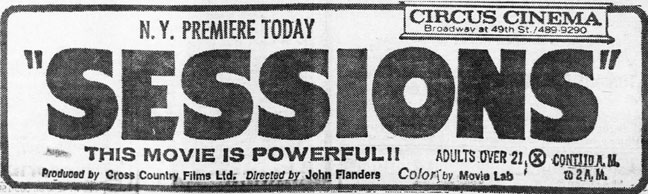

Cross Country’s first effort was the white-coater Sessions of Love Therapy (1971), which Al Jr produced, and a ‘John Flanders’ directed. The identity of Flanders remains another enduring mystery of the period. According to a recent interview with one-time California director Eric Jeffrey Haims, Haims himself was hired to assist Flanders in shooting the film’s sex scenes. Though that gig was strictly a perfunctory one-off affair, Haims still remembered Al Jr. and ‘John Flanders’, the latter being someone whose real name was different.

As for Al Jr., he loved the experience of making a sex film, and would dine out for years on his stories relating to ‘Sessions of Love Therapy.’ In a 2009 interview, he declared, “I told my crew, ‘Make this picture in three days but I’ll pay you for five.’ And then we went in and did all the sex in one day.”

The film follows the white-coater template than Harold had adopted for his films – namely a sex therapist advises four young couples – and it featured a stellar cast of who’s who in XXX films at the time, such as Keith Erickson (as Eric Keith), Suzanne Fields (as Cindy Hopkins), Ric Lutze, Rene Bond, Sandy Dempsey (as Tiffany Stewart II), and Sandy Carey (as Ann Wayne).

Al Jr. also claimed that his old friend from the burlesque circuit, Sammy Davis Jr., was present for the shoot: “Sammy was a porn freak. He visited the set and found it so quiet. He said to me, ‘You can hear a pube hit the ground!’ Whenever we made a picture, Sammy had to get a copy of it.”

According to Al Jr., Sammy even held a wrap party for the cast at the Ambassador in Los Angeles, and when the movie was finished, Al Jr. rented a theatre and ran it at two in the morning so he could show it to Sammy.

‘Sessions of Love Therapy’ opened in June 1971 at Royce Adams’ Capri in Buffalo, before Al played it at his own Capitol Burlesk Theater in Atlantic City. It finally opened in New York City at the Circus Cinema in November 1971.

Al Jr. shows his film ‘Sessions of Love Therapy’ at his Capitol Burlesk theater

Al Jr. shows his film ‘Sessions of Love Therapy’ at his Capitol Burlesk theater

The film endured an eventful history, being seized on several occasions – including in 1972, at the Eckel Theater in Syracuse operated by Royce Adams who was fined for showing it – though the seizure was later ruled illegal.

‘Sessions of Love Therapy’ was another white coater, and essentially a remake of Harold’s ‘The Postgraduate Course in Sexual Love’ but with a bigger budget and directed by ‘John Flanders.’ (‘Flanders’ had also been listed as the producer of ‘Postgraduate.’) This begs the question: was ‘John Flanders’ actually Harold Kovner?

Supporting this possibility is that ‘Flanders’ has another directorial credit, The Undergraduate (1971), a pseudo-instructional film which also has a strikingly similar structure as Harold’s ‘Postgraduate.’ Intriguingly, there was a second Cross Country feature film produced by Al Jr. and Royce Adams, the rarely seen The Hooker Convention (1972). Though without credits, it shares stylistic traits with Harold’s A Time to Love, including the same music and narrator.

Al Baker Jr. didn’t continue making adult films for long, and his interest in Cross Country Films had fallen by the wayside by the mid 1970s.

*

Fast Forward – Al Baker Jr.

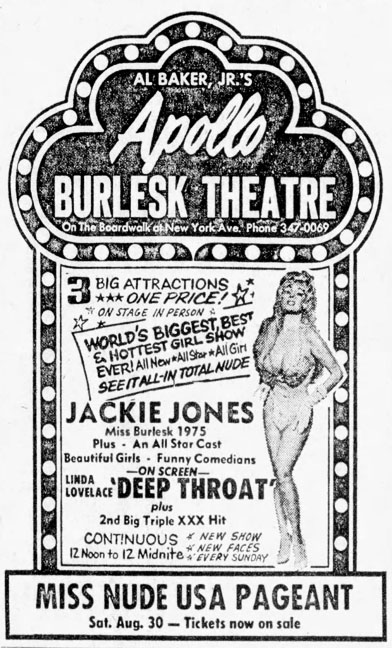

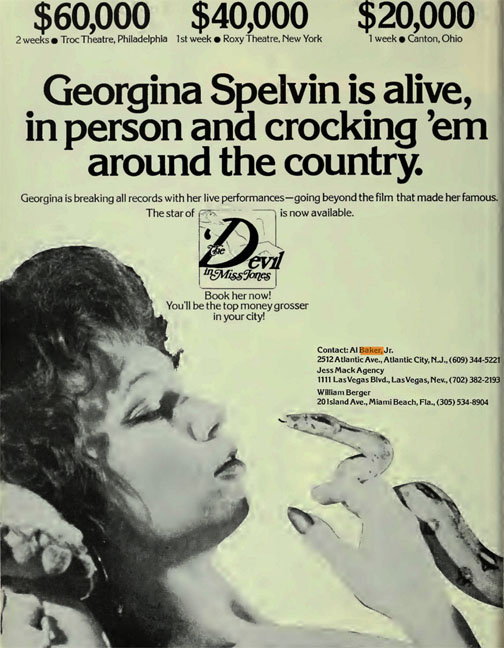

In the mid 1970s, Al Jr. was still running burlesque theaters in Atlantic City – including the Apollo Burlesk Theater and the long-running Capitol. The era of porno chic lingered, and he often showed XXX films in between old-school striptease acts. Al Jr. even spent a short time managing adult film star Georgina Spelvin, promoting her show at his Trocadero Theater in Philadelphia, an act that came with two snakes, a Q&A, and a simulated sex scene on stage.

Al Baker Jr. show in a double bill with ‘Deep Throat’, 1975

Al Baker Jr. show in a double bill with ‘Deep Throat’, 1975

Harold and Al Jr. saw less of each other as the 1970s wore on, but enjoyed the occasional reunion when they found themselves in the same town.

The entertainment business had been good to Al Jr. and when his theater business declined, he settled in south Florida, owning a number of bars, restaurants, and night clubs. The Miami Herald ran a story on him and a $110,000 rotating bed that he showed off at his home.

For years he prospered but there were a few bumps along the way. In 1992, he opened Mario’s East of South Beach restaurant, but in 1993, he was strong-armed to hand it over to the Mob who turned it into Mickey’s Place in partnership with actor Mickey Rourke. Then he opened a luxurious night club in North Miami Beach called Façade, but was quickly evicted after rumors of financial irregularities. It didn’t help that someone demolished the place with a chainsaw.

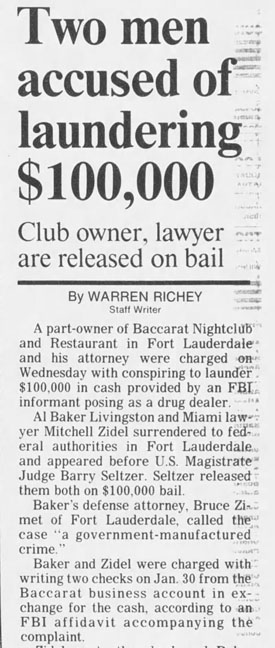

By the mid 1990s, it was widely rumored that Al Jr.’s businesses, and perhaps Al Jr. himself, were controlled by the Mob – and that he had been laundering dirty money for years. He wasn’t helped by the company he kept: he opened Baccarat Nightclub and Restaurant in Fort Lauderdale with Thomas Ruzzano, a known associate of New York’s Genovese family.

In 1996, Al Jr. and Ruzzano were approached by a drug dealer who offered them cash in exchange for two checks from the Baccarat business. They agreed to the transaction: the cash received was laundered through the business over a weekend, and the check was post-dated for the following week so as not to raise suspicions. Ruzzano went further and suggested that they create fake dinner and bar receipts for the items to justify the cash influx. It was a quick and easy deal. Except that the drug dealer was actually an FBI agent, and all their interactions had been recorded. Al Jr. was charged with money laundering using his businesses. The evidence was stacked against him, but somehow he beat the rap.

Towards the end of his life, Al Jr. was interviewed for the documentary Behind the Burly Q (2010). The director, Leslie Zemeckis, described him as “a short stack of energy, still handsome with dark hair, shirt unbuttoned down to his stomach, revealing a hairy abdomen with a nasty scar slicing through him, the result of recent heart surgery. Around his neck he wore a big gold chain that spelled “A.B. Jr,” a chunky gold watch, and a big diamond pinky ring. He also wore blue-tinted glasses and chewed a wad of gum throughout the interview. He was still the charming ladies’ man.”

Al Jr. died in 2012.

*

In the next and concluding parts of ‘Harold Kovner – Rewind and Fast Forward,’ stories of adult films, NYPD busts, Vanessa Del Rio, allegations of Mob-controlled child pornography, and the surprising conclusion to the divorce court case.

*

This is a towering achievement of investigative reporting. Quite how you track down so many people and re-create such a multi-faceted story is breath-taking. I am thrilled by this story…. about someone who I had never even heard of. I eagerly await the conclusion of the story.

We appreciate it DJT!

I love the story-telling ability here. You have incorporated so many characters who lived such incredible lives, and woven it all into a narrative that is completely compelling.

It strikes me that in among the adult film themes here – you are actually telling the story of America: crazy pioneers and adventurers that have built this tapestry of a country. It is rich indeed.

It really is like the story of America – good call!

Awesome Article Keep Up Good Work

I wonder what happened to the Rosenzweigs? Can’t find any info about the upshot of the case.

No audio for this one? I love these stories but I can only listen to the audio ones as I put them on at work to pass the time. Wish they all had narration

I’m not gay, but that photo of Jaime leaves me jealous of what he once looked like.

“It’s a Revolution Mother” is a great documentary of a tumoltous time in history and look into both the hippie , yippie , and biker counter-culture as well as the Vietnam war. A true masterpiece in it’s own way.