In 2025, The Rialto Report facilitated the purchase of one of the most important film collections in adult film history – the Mitchell Brothers Film Group (MBFG) library – by Distribpix Inc. & Vinegar Syndrome.

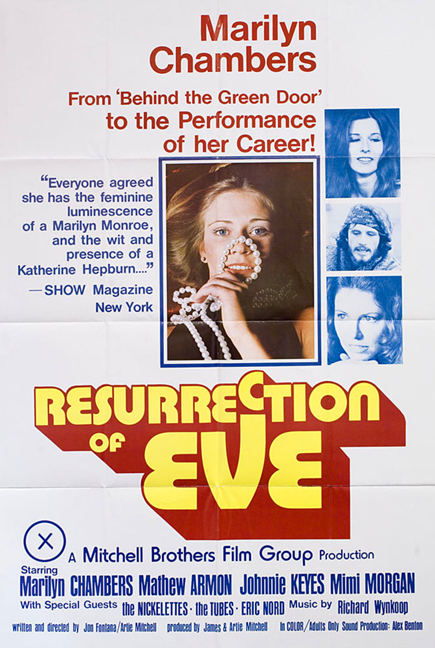

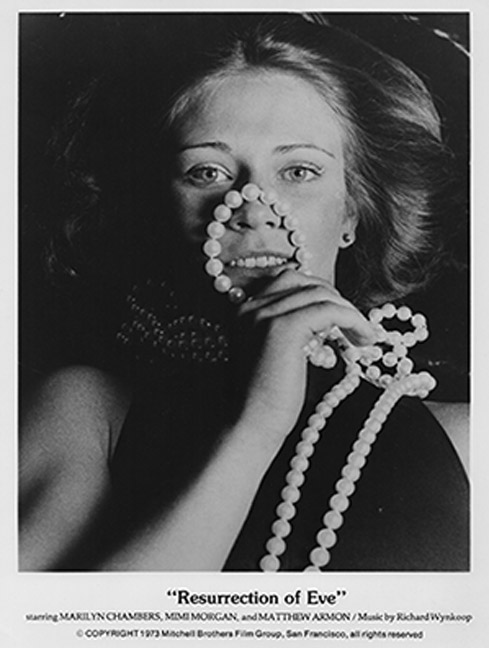

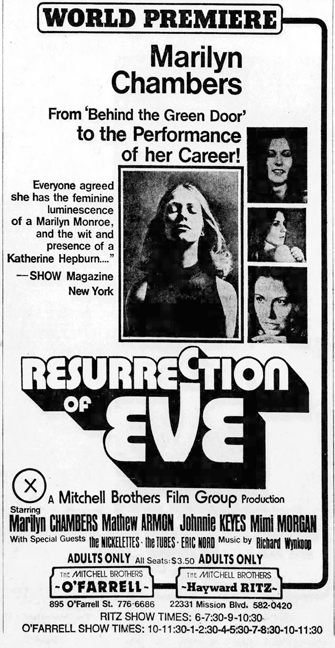

Since then, two of the landmark MBFG films, Behind the Green Door (1972) and Resurrection of Eve (1973), have been released in special limited edition Blu-ray packages featuring multiple extras, including interviews, commentaries, essays and more.

This week, we look back at the lesser-known and often-neglected ‘Resurrection of Eve.’

You can buy Behind the Green Door (1972) and Resurrection of Eve (1973) here.

With thanks to Steven Morowitz and Melusine for their support.

——————————————————————————————————————————

You know that problem when you and your friends get together, mess around for a few months, and change the course of film history – and then you have to try and figure out what the hell you’re going to do next?

No. Me neither.

But that was the dilemma facing the maverick Mitchell brothers in the wake of the extraordinary triumph of their feature film, ‘Behind the Green Door’ (1972). To put it simply: how do you follow up one of the most successful, influential, and – let’s face it – unexpected successes in the history of underground cinema?

It was supposedly made with a budget of $50,000, it supposedly achieved a nationwide theatrical box office of $5 million, and it supposedly grossed upwards of $50 million including video sales. ‘Supposedly’ is doing some heavy lifting here: after all, this business was an under-the-counter, disreputably-secretive, shady and corrupt, all-cash industry where no one could even agree if the final product was legal.

No matter. What is verifiably true however is that ‘Behind the Green Door’ became such an unprecedented porno hit (only Deep Throat (1972) could claim to have come close) that it tore up the rule book for what a sex film could achieve. Not only that, but – unlike ‘Deep Throat’ – intellectuals dug it too. Indeed, when Derek Malcolm, the much respected, high-brow, and stuffiest of British film critics was asked in 2000 to name the best 100 films of the 20th century, he excluded Orson Welles ‘Citizen Kane’ completely – but found a place for ‘Behind the Green Door.’

So how did this happen?

Reader, the story behind ‘Green Door’ has been told so many times that it seems almost superfluous, redundant, insulting even, to repeat it again here. But for the benefit of anyone emerging from a monastery for the first time in almost 60 years, let’s tell the story one more time.

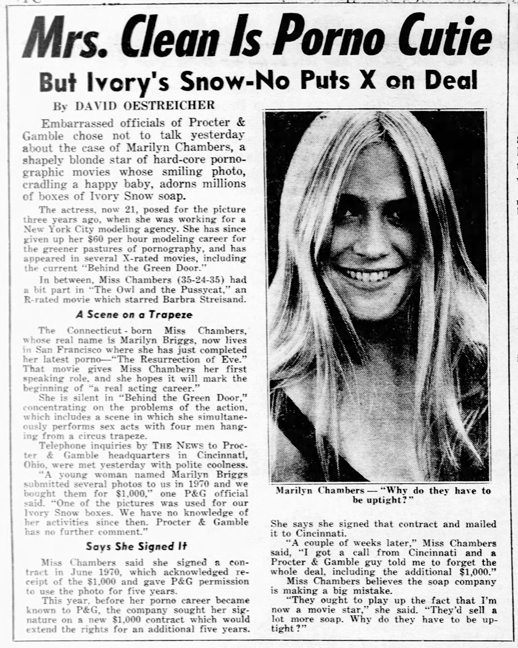

In 1972, Jim and Artie Mitchell were casting the lead role for their new sex film – and happened upon blonde, willowy Marilyn Chambers, a model who’d just appeared as Proctor & Gamble’s ‘Ivory Soap girl’ in an ad campaign featuring the brand’s slogan “99 and 44/100% pure.” The Mitchell brothers duly appropriated the same virginal concept for their own fuck-flick marketing, thereby capturing the imagination of every red-blooded male in the country who duly flocked to their local skin palaces to witness this innocent blonde performing unspeakably slutty acts. The gimmick worked: in the words of Variety at the time, ‘Green Door’ was a “boffo, socko success” – as well as the subject of television talk show monologues, schoolyard jokes, not to mention threats of lawsuits from a panicked Proctor & Gamble.

Apart from the P&G execs, everyone was happy.

But every silver cloud has a lining, and this unexpected success left the newly-millionaired brothers with an unfamiliar problem: could they capture lightning in a bottle for a second time?

The Mitchells may have looked like Scooby Doo’s hippie entourage, but they were smart amd wily businessmen – and they relished the challenge. They started by meticulously taking the ‘Green Door’ concept down to the studs and identifying the elements that had caused its success, then set about trying to replicate each of them in their next film.

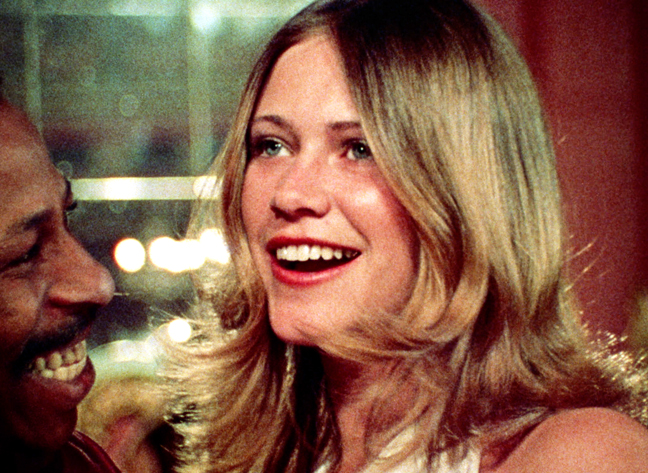

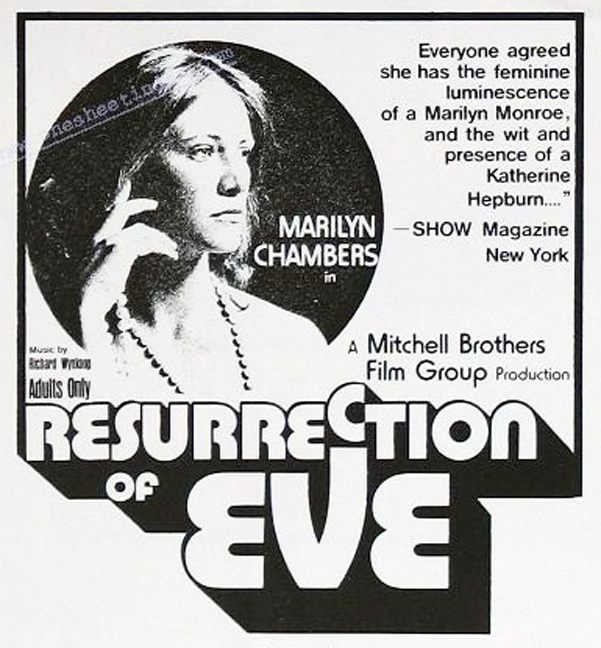

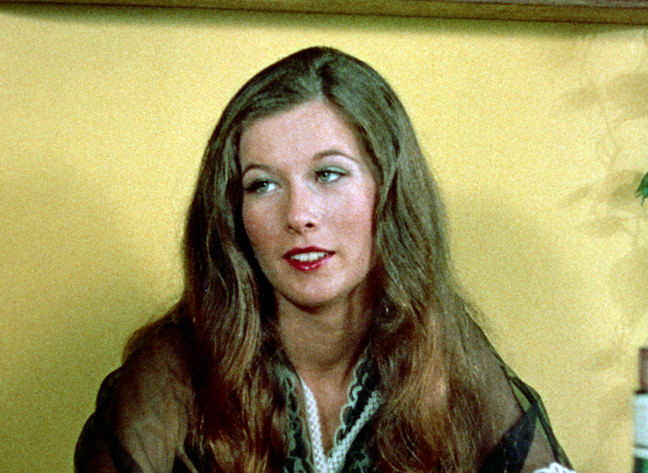

They started with the obvious standout feature: Marilyn Chambers. She was now a household name, guaranteed box-office, and the nation’s new favorite sex symbol. (Put it this way: the two biggest female screen stars of 1973 were Ellen Burstyn, who’d just starred in ‘The Exorcist,’ and Barbra Streisand, fresh from the hit ‘The Way We Were’, and no one, repeat no one, was clamoring to see either of them doing the no-pants dance.) So it stood to reason that Marilyn had to be the star of the new movie, her image had to be emblazoned across posters, and she had to tour the country from coast-to coast making personal appearances. So far, so simple.

Then there was the fact that ‘Behind the Green Door’ had a plot. Well, kinda, sorta-ish. It had been adapted from an anonymous short story of the same title circulated extensively over the years in the form of well-thumbed, pirated photocopies passed around by one-hand strummers. The storyline was admittedly slight, though you could just about see it if you squinted – so it was decreed that the next film should follow suit and have a more intricate plot just like a regular film: you know, think, ‘Last Detail’ (1973), think ‘Last Picture Show (1971), don’t think ‘Last Dildo in Paris.’ Further, this story needed to appeal to a new breed of porn-watcher: namely, women. Yes, newly-emancipated boho babes, flower children, earth mamas, and suburban sisters, who, let’s face it, were more intelligent and discerning than your average porn hound and who demanded more than just banging for their buck. In short, if the next movie was to be a hit, it didn’t just need butts in seats: it needed female butts in seats.

Then there was the outre’ nature of ‘Green Door.’ That film had featured an interracial sex scene – shock, horror, the first in a hardcore feature film – starring ex-‘Hair’ performer Johnnie Keyes as the African American dick. Not kinky enough for you? How about a seven-minute psychedelic sequence featuring multicolored, slow-motion, optically-printed, close-ups of ejaculation flying through the air. Happy now? You’re welcome.

Finally, the new film had to look good. If you wandered in off the street, it should play like a European art house movie unspooling at a respectable theater. Or to put it another way: it should be infinitely better-looking than the majority of run-of-the-mill one-day-wonder sex films being made at the time.

So, to summarize: the new film had to be a well-made Marilyn Chambers vehicle with an intelligent, female-centric plot, taboo-busting sex, all filmed with skill and aplomb.

And so, Jim and Artie made ‘Resurrection of Eve.’

*

If the Mitchell brothers’ entrepreneurial instincts represented capitalism in its purest, unfettered form (“our early motivation was almost 100% for the money – there was never any other motivation, it’s always a hustle, a way to make some bucks,” they said in an interview in ‘Sinema’), their work process was surprisingly and unapologetically socialist. Every Mitchell Brothers production was a collaboration involving childhood friends, extended family members, semi-celebrities, iconoclastic eccentrics, and maverick misfits. Contrary to belief, there was no such thing as a Mitchell brothers’ production: sure, the brothers were obsessively controlling by nature, but they also recognized the power of the collective and had little ego-driven pride of ownership.

Take ‘Eve’ for example: it was directed by their compadre and brother in arms, Jon Fontana, who became the movie’s principal creative force, co-directing, co-writing, shooting, and editing the whole shooting match. Fontana was one of the ‘Tiochers, the trusted group of childhood friends from Antioch, the city in the East Bay region of the Bay Area, ninety minutes outside of San Francisco, where Jim and Artie had grown up. Fontana had been the main cameraman of their filmmaking posse from its early days, and he jumped at the opportunity to produce a film of his own.

Fontana’s production team was peppered with inner-circle intimates and outer-circle acquaintances – most of them performing multiple roles. Fellow ‘Tiocher, Alex Benton produced and did the sound, and Jim’s erstwhile close friend Dana Fuller was the gaffer. Mark Bradford, brother of Artie’s first wife Meredith, who had eschewed a blue blood education to help build the Mitchell’s HQ the O’Farrell Theater (according to legend he used his .22 pistol to drive the bolts that anchored the theater seats to the ground) was key grip, editor, and special effects coordinator. Mark Bradford’s best friend, Phil Heffernan, the O’Farrell’s art director (and future Thundercrack! (1975) actor, ‘Mookie Blodgett’) did the fancy credit sequences, while Jerry Ward, Artie’s hard-drinking, wise-cracking army buddy who’d become the O’Farrell’s general manager, took Production Manager duties (together with filmmaker/model girlfriend Loralyn Baker) as well as an acting role. Bob Cecchini, another ‘Tiocher and Jim’s first roommate in the city back in the mid-1960s, had responsibility for finding actresses, and took all-important publicity still photographs together with ubiquitous sexploitationer, Bill Rotsler.

The music soundtrack – a competent jazzy, funky score – used sparingly and sometimes disappearing behind the sound of the actors’ heavy breathing, came courtesy of another member of the Mitchell’s repertory group, Richard D.F. Wynkoop. A staple of the local music scene, he was later hired by the Mitchells to coach Marilyn in a bid to launch her singing career. (The rumor that his initials ‘D.F.’ stood for ‘Doesn’t Fuck’, referring to Wynkoop’s celibacy, are unsubstantiated.)

Perhaps remarkably, all of the production crew used their own names – unusual for a porn film of the era – because… well, why wouldn’t they? They were loud, proud, counter-cultural pioneers, goddammit, unruly and unkempt step-children of the Tenderloin who’d created “the Carnegie Hall of public sex in America” (to quote Hunter S. Thompson): to hide behind noms-de-porn would surely be ignoring their essential raison d’être.

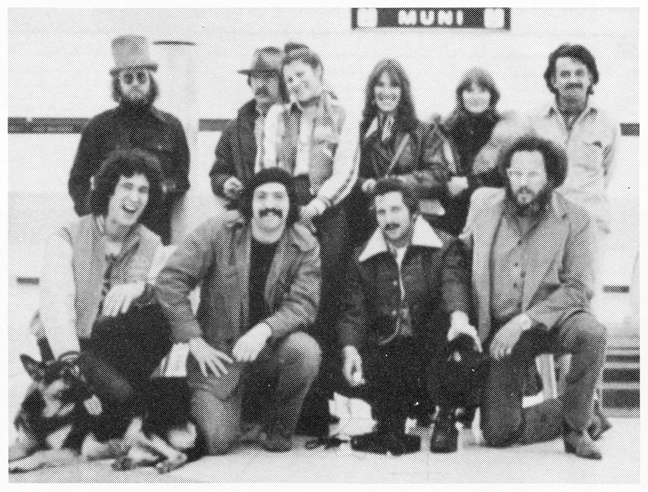

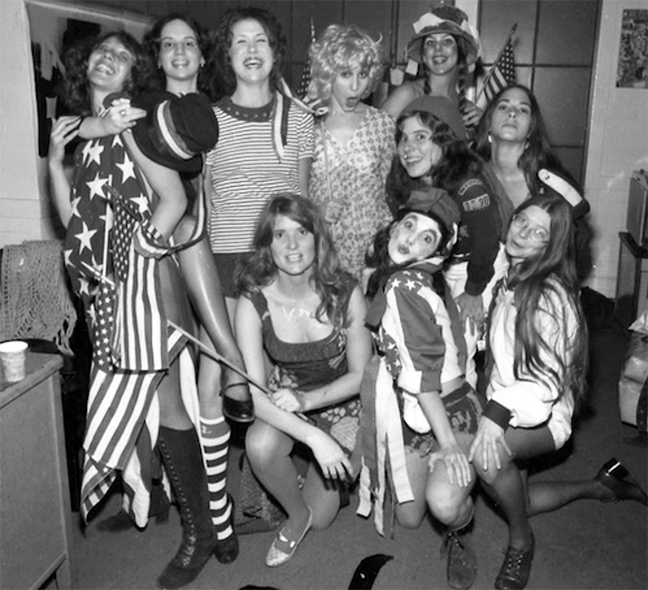

(back row, l-r) Artie Mitchell, Jim Mitchell, Jim’s wife Adrienne, Denise Larson (lead Nickelette), unknown, Vince Stanich.

(back row, l-r) Artie Mitchell, Jim Mitchell, Jim’s wife Adrienne, Denise Larson (lead Nickelette), unknown, Vince Stanich.

(front row, l-r) unknown, Andy Finley, Jon Fontana, Bob Cecchini

The egalitarian socialism of the production crew did not extend to the actors, where a distinct two-tier class system persisted. Aside from exceptions that included Marilyn Chambers and George McDonald, the talent was more transactional and thus expendable, and didn’t mix socially with the Mitchell Brother Film Group clique.

For ‘Eve’, two established theatrical actors were chosen for main roles: Matthew Armon, who played the male lead, was a classically-trained Shakespearean actor based in Santa Cruz who was appearing in a production of ‘Hamlet’ while ‘Eve’ was being shot. Dale Meador, who played the role of an aging pedophile, was a theater director who’d produced Gertrude Stein’s ‘Faust’ the previous year. (He’d also submitted a proposal to the Petaluma Recreation Commission requesting permission to hold classes for children to dramatize classical literature. Whether the Commission was aware of Meador’s hardcore portrayal of a child molester in ‘Eve’ that same year is unknown.)

A variety of familiar faces fill other roles, including Mimi Morgan (her first of many X-rated parts), Johnnie Keyes (reprising his ‘Green Door’ role), San Francisco regulars Kandi Johnson, Tyler Reynolds, and Jon Martin, Zachary Strong (future prolific director and actor), Mark Ellinger (who scored many San Francisco underground films), Jerry Abrams (rock concert light pioneer and 8mm loop-meister), and even Curt McDowell (Kuchar, ‘Thundercrack,’ et al).

A mention should go to the presence of Les Nickelettes, a bawdy, all-female theater troupe that performed cabaret-style, satirical, and comedic acts at the O’Farrell. They worked independently of the Mitchell’s adult film productions but were added to the cast of ‘Eve’ to showcase their act.

*

‘Eve’ took two months to film, twice as long as it took to make ‘Green Door,’ with much additional, unused footage being shot. It was the brothers’ first movie shot on 35mm.

It was filmed at a variety of San Francisco locations, with the climactic orgy taking place at the Great American Music Hall, two doors down from the O’Farrell. Jim, perennial shit-stirrer and always publicity-savvy, invited the media to see the bacchanalian scene being shot, and, unsurprisingly, it proved to be a popular gig for the newsmen. Apart from skin magazine scribes, reporters from mainstream channels turned up, including TV companies ABC and CBS, making the actual shoot almost impossible to execute.

Did all of the pre-planning ideas show up on the screen? Many did and, if anything, the Mitchells over-indexed on some of the qualities they’d identified as being key to the success of the new film.

For example, ‘Resurrection of Eve’ has an intricate plot which plays out in a nonlinear, deliberately-disjointed, quasi-avant garde narrative – unheard of in a fuck film, and seen only occasionally in European movies such as Bertolucci’s ‘The Conformist’ (1970) or Antonioni’s ‘Zabriskie Point’ (1970).

Or there were the three separate actors that play Eve, decades before Todd Haynes’ experimental Bob Dylan biopic, ‘I’m Not There’ (2007), which cast six different players to depict various facets of Dylan’s persona.

Or the vivid, primary colors of the cinematography, evoking ‘The Wizard of Oz’ (1939), ‘Vertigo’ (1958), or ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ (1968).

As for having high-brow artistic credentials, how many other porn films start with William Blake poetry? (Spoiler: none.)

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Let’s start by revisiting the plot: Eve is sexually abused as a young girl. Then her appearance changes (new actress, please!) and she meets a San Francisco DJ named Frank Paradise. He’s a porn stereotype: he has sex with everyone but is also insanely jealous. So Eve spends time with boxing star and returning hero from ‘Green Door,’ Johnnie Keyes. Eve and Frank quarrel, but when she flees, she has a car accident that disfigures her. No reason to panic though: the doctors can give her a new face (another new actress, please!) Not only that, but when the bandages are removed, Eve is prettier than ever. Frank is so pleased with the plastic surgery that they get married, but no sooner than she says, “I do”, he’s back to his old ways, this time trying to interest her in group sex. She resists at first, of course, horrified by what she sees. Frank berates her for cramping his style, so she tries swinging again, and this time… well, you know, she realizes it’s actually great. In fact, it liberates her, gives her a new-found independence, and best of all, she decides to leave Frank.

So, is the resulting film any good?

It’s a strange concoction that shouldn’t work – but it almost does and, in some respects, it’s a superior film to ‘Green Door.’ Some critics picked up on the feminist overtones, and compared its sexual politics to mainstream films like Paul Mazursky’s ‘Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice’ (1969) or Mike Nichols’ ‘Carnal Knowledge’ (1971). It is certainly true that the Mitchells & Co. were tackling subjects from angles rarely explored in early XXX efforts.

Strangely, for all its claims to be another transgressive work featuring all manner of sex – gay, straight and interracial – ‘Eve’ is not a particularly explicit film with only brief sequences of hardcore footage. Critics have suggested that this was due to the ongoing Supreme Court case, Miller v California, which was establishing the legal definition of obscenity and was taking place while ‘Eve’ was in post-production. (The verdict eventually came in June 1973.) It is more likely that the film was being aimed at an artier crowd, and thus usual grindhouse tropes were scaled back.

*

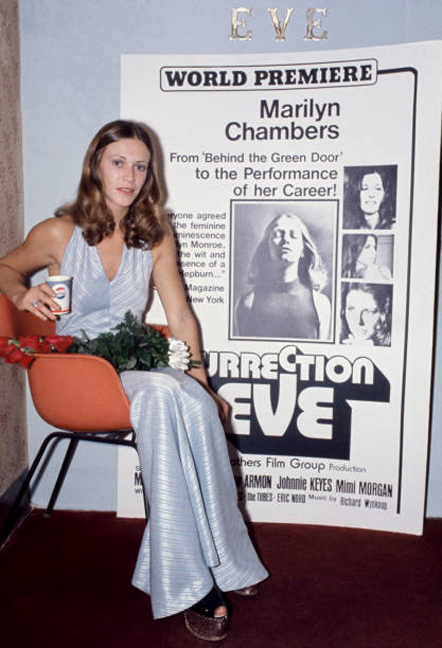

‘Resurrection of Eve’ was released nine months after ‘Behind the Green Door’ in September 1973, with a premiere at, where else?, the O’Farrell.

It wasn’t nearly as successful as ‘Behind the Green Door’ but, in truth, no one expected it to be. Part of the reason was that times had changed – even in the twelve months since ‘Green Door’ had been released. ‘Behind the Green Door’ had been a coincidence of circumstances that could never be repeated. The ‘porno chic’ moment had passed, and it was no longer as novel to watch explicit sex on screen.

However, the film was a reasonable hit: the Ivory Snow controversy was still rumbling on when ‘Eve’ was released, and Marilyn was always an asset for media duties. She gave countless interviews, coming across as thoughtful, intelligent, and wholesome. “It’s really going to appeal to a female audience,” she told Show magazine with great enthusiasm. “It’s a film about today – women want to be equal; they don’t want to be pushed around by men and treated like creatures of a lower order.”

In a strange twist, following the release of the film, Marilyn’s life resembled that of her character Eve’s. In early 1974, she became friendly with Chuck Traynor, the former manager and now ex-husband of Linda Lovelace. Lovelace alleged that Traynor abused her, but despite his reputation, Marilyn signed a contract with Traynor for him to become her manager. The Mitchells, who considered Marilyn their property, reacted angrily to the news: Marilyn was still making waves as the Proctor & Gamble legal case rumbled on, and the brothers wanted to keep cashing in. Traynor’s presence put a stop to the Mitchell-Chambers relationship and, in retaliation, the brothers put together a pseudo-documentary, Inside Marilyn Chambers (1975) consisting of some of the discarded footage shot for ‘Resurrection of Eve.’

*

Having a perspective on ‘Resurrection of Eve’ today is something of a Rorschach test. Did it cement the Mitchell Brothers’ reputation as ambitious adult filmmakers in their bid to set themselves apart from what their competition was doing by appealing to mixed audiences? Or was it an under-performing flop, weighed down by incomprehensible storytelling and inconsistent acting?

Perhaps neither point of view is relevant today compared to the main question: is it an enjoyable watch? If the one unforgivable sin is to be boring, ‘Eve’ is an entertaining, good-value romp, full of the qualities that make golden age adult films simultaneously compelling and exasperating. It showed that hardcore films could have a long, bright future co-existing alongside mainstream cinema. Except that we now have OnlyFans instead.

*

*

An excellent, insight, and most-of-all very well-written essay on a neglected classic!

Laugh-out-loud humorous – as well as fascinating. I appreciate the way that TRR focuses on lesser known works (and people) and not just the obvious works. This article is a smart breakdown, and just good feature journalism. I wish that there was more out there in XXX, but it seems like TRR is the sole example. Good to have such an incredible collection of work.

Happy Birthday Rialto Report!

It’s been 13 years of consistent, high quality journalism. you are the best. May you never stop!

Excellent – but one peeve: why wasn’t this included in the BluRay package (which is otherwise amazing)? It is infinitely better than the other essay. Keep up the god work.

Mimi Morgan was great. But it seems she ended her career early. Whatever happened to her?

Awesome Article Keep Up Good Work