Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

Cuba may only be 90 miles from the southern tip of the United States – a leisurely boat trip on a calm day – but since the 1950s, the island has seemed part of a distant world, too many communist miles away.

It wasn’t always the case. For years, Cuba was almost an extension of America, almost another star on its star-spangled banner. Links between the two countries dated back to when the Cuban cigar industry first arrived in Florida in the 1830s, and Hispanic communities developed in Miami as impoverished Cubans emigrated, dissatisfied with Cuba’s poor economy, a high poverty rate, and the various military dictatorships. Cuban tourists followed and soon the city became home to a variety of Spanish language amenities.

And then on January 1, 1959, everything changed: Fidel Castro’s communist rebels seized control of Havana, Cuba’s capital. The new dictatorship reduced American influence on the island and, by the early 1960s, had seized all American-owned property in Cuba. The United States responded with an embargo restricting commerce between the two countries, which is still in place today.

Many Cubans, fearing the consequences of Castro’s new revolutionary government, fled to the nearest part of America, the state of Florida, and that influx of people changed Miami: before the revolution, just 10,000 Cubans lived there, but three years later, in October 1962, nearly 250,000 more Cubans had arrived, and that number would grow to over 1,000,000 by the 1990s.

Many of the new arrivals had been professionals and tradesmen back in Cuba, and they arrived in Florida looking to continue to work in their chosen fields as doctors, lawyers, auto-workers, and manual laborers.

And then there were those who’d worked in Cuba’s film and television industry.

Over the last twenty years, I’ve tracked down and spoken to many Cubans who worked in the Florida film business in the 1960s and 1970s, people who made their home and careers there after escaping their home country. Their accounts uncover a Rashomon collection of overlapping personal histories that reveal an untold chapter of adult film and the hidden role that Cubans played in shaping it.

These are some of their stories. This is Chasing Butterflies: Stories of Cubans in Exploitation-Era Florida. This is Dolores Carlos‘ story.

With thanks to John Minson, Tom Flynn, Ronald Ziegler, Veronica Acosta, Mikey Bichette, Bunny Downe, Mitch Poulos, Sheldon Schermer, Ray Aranha, Barry Bennett, Randy Grinter, Michael Bowen, Norman Senfeld, Richard Falcone, Something Weird Video (nearly all films mentioned in this series have been found with them), and many anonymous families and friends who have offered recollections, large and small, over the years.

This podcast is 41 minutes long.

—————————————————————————————–

1. Dolores at the Opa Locka Community Center

Every time Dolores Rose went to the weekly women’s group at the Opa Locka Community Center near Miami, she made sure she dressed well. She’d have her hair piled high, a string of fake pearls around her neck, high-heeled espadrilles, and she could still fit into her powder blue cigarette pants. Sure, she was the wrong side of 60, and she knew that being old was mandatory, but looking old was optional. This was no God’s waiting room for her, this was her time to shine.

This week’s gathering was more special than usual for Dolores. Each meeting was turned over to a different woman who’d make a presentation to the rest of the group about something of general interest. Pie-baking, bird-watching, bee-keeping, flower-arranging, that sort of thing. Sometimes the only really interesting part was when the discussion was derailed by the profane, never-ending questions that came from an elderly Jewish woman named Freida.

This week was Dolores’ turn to present.

She steadied herself at the front of the noisy group, and took a breath.

“I wanted to tell you about a long time ago,” she said, “when I was a big star in sex films.”

A silence descended on the room like a thick wet blanket.

Frieda whispered loudly, “Holy shit. Did I come to the right meeting?”

*

2. Dolores Xiques

Dolores Xiques was Cuban through and through.

No matter that she was born in Tampa, Florida in October 1930, and never even visited her country of origin. Her Cuban heritage and looks, not to mention her patriotism, all came from her father, Gus Xiques, a fervently passionate Cuban, though ironically, he too was a Floridian, born in Monroe County in 1899.

Gus was a cigar maker who’d inherited the family business from his father Carlos. He raised a family of four in northern Florida by himself after his Cuban wife passed, and Dolores was his youngest child. He was a strict, hard-working man, and top of his belief hierarchy was loyalty to their country of origin and to their fellow Cubans. Not just any Cubans, but American-Cubans. Gus taught each of his children that all Cuban immigrants had endured a common journey, a mutual struggle, and they could collectively survive in America only if they helped each other out. Supporting fellow Cubans should always be a priority in their lives.

Dolores’ family was a tight-knit one (papi Gus re-married after Dolores’ mother died – to another Cuban woman, of course), and Dolores grew particularly close to her grandfather, Carlos, a one-time cigar-maker from Camaguey, Cuba, who’d emigrated to Key West, Florida back in September 1886.

Gus and his family lived at 3405 Green St, Tampa, and Dolores attended nearby Jefferson High School where most of the students were Hispanic or black, drawn from the adjacent Latino communities of Ybor City and West Tampa.

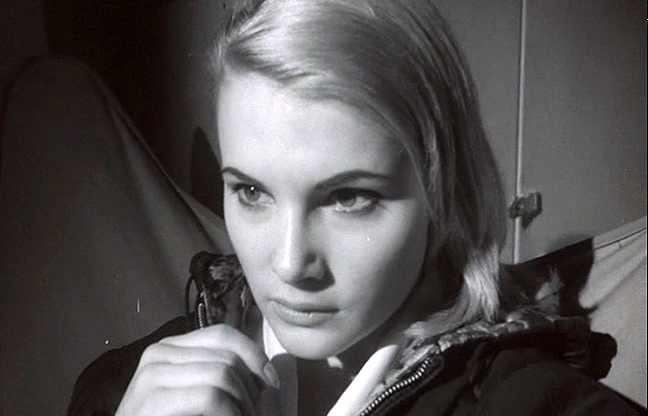

Records suggest that Dolores did well in school – her grades were better than most, and she was pretty and popular. But family members say that, as she grew into her teens, she longed to step outside of the strict confines of her Latina family. Against her father’s wishes, she’d sneak out of school, often ending up in movie theaters, where she’d gaze at her idols, Jean Harlow and Rita Hayworth, and craved a more independent and glamorous life. In school, she joined theater, music, and dance groups but somehow it didn’t feel enough. She wanted more. Her ticket out came in 1947 when she was 17, in the form of Maurice Bichette, a dashing and handsome New Yorker from Orangeburg, ten years her senior.

Maurice had a mildly checkered past: he had three kids from a previous marriage, was in the middle of a divorce, and had picked up a couple of arrests for reckless driving that would eventually lead to losing his license. Seeking a fresh start, he’d moved down to St Petersburg where he found work with the Clear-View Venetian Blind Company. He had a few goals: he was looking to stay straight, get a job, settle down – and part of that whole equation entailed finding a wife.

It was a whirlwind romance: Dolores and Maurice announced their engagement just months after meeting, and tied the knot on May 9th, 1948, settling in St Petersburg at 4465 Crestwood Drive North. The engagement announcement in the newspaper featured a close-up portrait of Dolores with a flower in her hair – looking like her idol, Margarita Cansino, the actress of Spanish descent who became a huge star after changing her name to Rita Hayworth.

Dolores and Maurice were both good kids: their problem was that they just weren’t good for each other, and cracks in their relationship appeared quickly. Part of the issue was age-related: Dolores graduated high school the same month as their wedding, Maurice was her first boyfriend, and she was just looking to leaving her strict family home and enjoying greater freedoms. She wanted to experience racy, swashbuckling adventures like those described by her grandfather Carlos. Maurice on other hand, trying to correct the errors of youth, was looking for a quieter, more settled life.

For a time, they made it work: they fixed up their new home, took vacations down in Miami, and in August 1950, Dolores gave birth to their daughter, Marcelle Denise Bichette, who quickly became known as Marcy. It was a life-changing moment for both of them and baby Marcy became the center of their worlds. Over the next decades, no matter what else was going on in each of their lives, Marcy would always be their first priority.

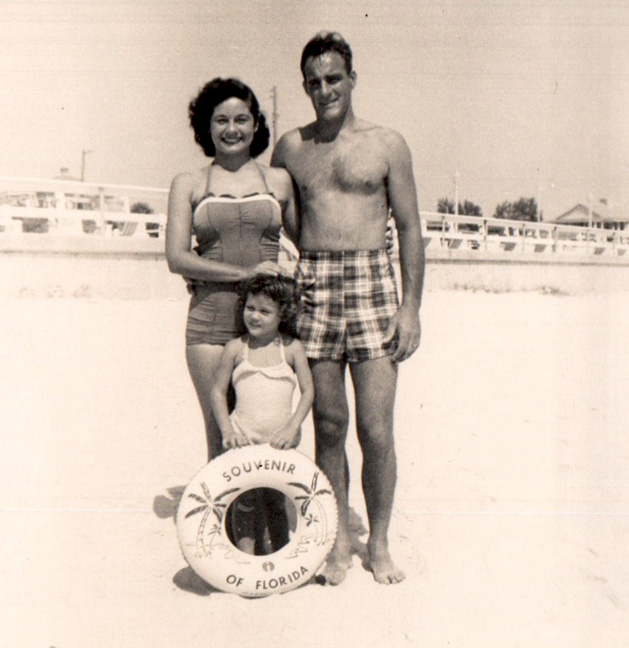

Dolores, Maurice, and Marcy, 1954

Dolores, Maurice, and Marcy, 1954

Dolores loved being a mother and doted on Marcy, but the realization was already dawning on her: had she had just swapped one set of restrictions for another? She was barely 20 years old, without a job, and now she was stuck at home with a new-born and daily chores. Housework can’t kill you, sure, but why take the chance? Had her dreams of being someone been crushed before she’d even begun? Arguments sparked between the couple: love may be blind but marriage was a real eye-opener for her. Dolores’ loneliness was made worse when she lost her beloved grandfather Carlos and then her stepmother within a year of Marcy’s birth.

Dolores, headstrong and determined as her father had taught her, decided she needed a career.

*

3. Dolores – The Model

In early 1953, Dolores sent off her resumé to Webb’s City in St Petersburg.

Webb’s was a one-stop department store covering ten city blocks. It was a precursor to Walmart, with 77 departments, 1,700 employees, and the slogan, “There’ll be no more hoppin’ around the town a-shoppin’. But instead of applying for one of Webb’s many sales assistant roles, Dolores had her eye on something more exciting: she wanted to be a model for them. Webb’s had historically been associated with elderly citizens keen to spend their pension money, but top management had recently decided they needed to change and appeal to a younger crowd, and so they started a model training program for girls between 15 to 20 years of age.

Dolores faced resistance from all sides: for a start she was already 23, her father, Gus, didn’t deem modeling to be a respectable occupation, and husband Maurice said it was a distraction from her duties as a mother. Furthermore, Webb’s model program was already over-subscribed. And then there was the fact that, well… Dolores wasn’t white, and Webb’s had always had a little racism problem. Sure, it was true that Webb’s would hire non-whites at a time when other businesses in St. Petersburg would not, but it was also the case that the non-white hires were used in positions that were less visible, and they weren’t permitted to eat at the lunch counter, and they weren’t eligible for promotion. This racial glass ceiling and discrimination at Webb’s would later become the focus of Civil Rights sit-ins and controversies during the 1960s.

But Dolores was determined and resourceful: she colored her black Cuban hair red, knocked four years off her age, stuck her thumb in the air, and hitched a ride to the store for an interview. She told no one what she was doing. Her application was a success, and much to the regret of husband and father, she was selected for Webb’s training program for teenage models. She figured she could keep her real age a secret, but then the local newspaper took her picture and published it under the heading ‘Teen Takes Fashion Spotlight’. Her father Gus and husband Maurice saw it and gave her hell.

But Dolores loved the opportunity, and when the training finished, she took a job in the store modeling clothes and swimwear. No one knew she was overage still, so she did modeling catwalks for teenage models, such as the annual Swim Party on the roof garden of Webb’s. Then at one of the events, she was spotted by a beauty contest organizer who learned that she was married, and invited her to represent St Petersburg in the Mrs. Florida contest – strictly for married housewives – that was run by the Palmetto Junior Chamber of Commerce. The event took place in August 1953 with 48 entrants from across the state – and Dolores was billed simply as ‘Mrs. Maurice Bichette.’ And if you ever thought that simple beauty contests were perhaps a little sexist, this one was rather more so: sure, it consisted of parading in the usual swimwear and evening clothes, but models also had to demonstrate housewifely skills such as sewing, cleaning, cooking, and child-raising, which accounted for 50% of the total score. In fact, Dolores was pictured in the newspapers showing her bed-making ability. She didn’t win the contest – which was a desperate shame as one of the prizes was a vacuum cleaner – but it wasn’t all in vain: her skeptical husband Maurice won the side competition to find the best-looking husband.

But happy moments like this between Dolores and Maurice were becoming less frequent, their arguments were becoming more heated, and in 1954, they decided on a trial separation. For the first time in her life, Dolores was on her own.

*

4. Dolores goes to Miami

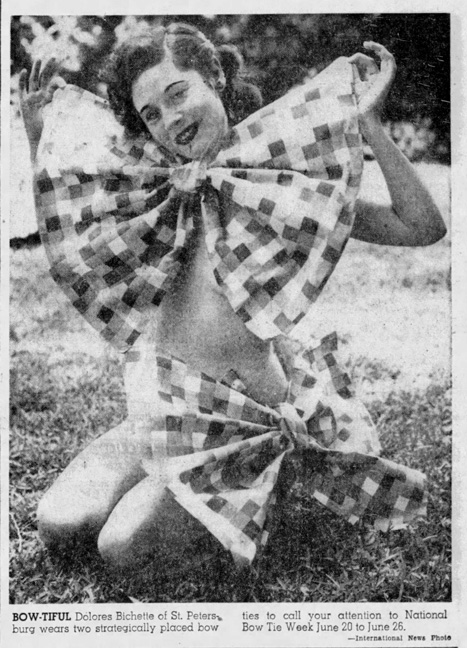

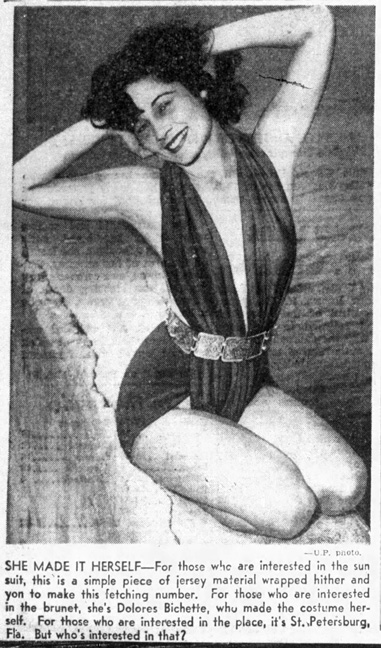

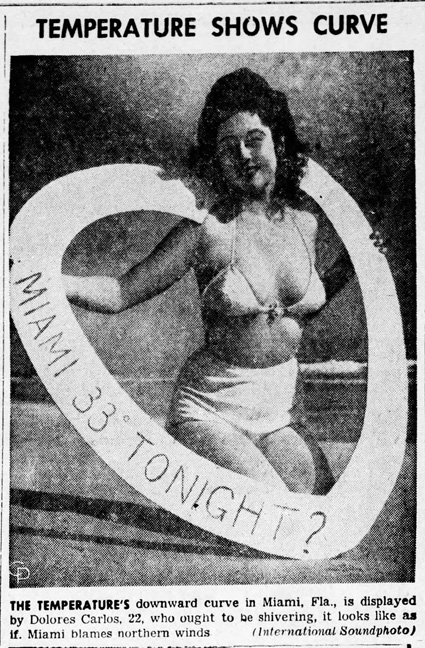

After the separation, both Dolores and Maurice both wanted custody of Marcy, so they agreed to share time with her. Dolores still had her job at Webb’s and she took care of Marcy on weekends. But money was short, so she took on new work as a dance instructor and did freelance modeling jobs across the St Petersburg and Tampa areas. She was attractive, and her eclectic portfolio of work started appearing in newspapers across Florida in different contexts: she was the daily ‘sunshine girl’ (typically posing with a giant thermometer to indicate that day’s temperature), she was elected as ‘Queen of Photography’ by the Central Florida Camera Club, posed for Bow Tie Week (nude with a couple of giant bow ties ensuring her modesty), she entered (and won) beauty pageants, and was selected by Coca-Cola to be on their float at the huge King Gasparilla Pirate Parade. She was surprised by her own success: her pictures were being published all over the country – even making it into the Daily Mirror newspaper in England, which, at the time, claimed it had the largest daily circulation in the world. All were tongue-in-cheek, slightly suggestive pictures, while still remaining innocent – and Dolores’ age was typically given as three or four years younger than she actually was. She’d figured out that the secret of staying young was to live honestly, eat slowly, and but most of all, lie about your age.

Dolores’ modeling career was taking off at the same time that any remnants of her relationship with Maurice were fizzling out. Attempts to reconcile had failed, and tension between the two grew as Dolores’ life became more glamorous and Maurice became increasingly disapproving.

In early 1956, they filed for divorce, and the following year, Maurice re-married. For Dolores, the final breakdown of her marriage was her cue to shoot for the big time. As much as she enjoyed the modeling though, she dreamed of making it in the film industry, and for that to happen, she knew she’d have to move to Miami, the only significant center for film production in the state. The problem was that moving to Miami – 280 miles and at least a four-hour drive away from St Petersburg – meant giving up day-to-day custody of six-year-old Marcy. It was a heart-breaking prospect and one she didn’t take lightly. After agonizing for weeks, she decided to give it a try.

In 1956, Dolores drove down to Miami. It was a new start which was exciting, but she had the support of precisely no-one. She decided she needed a new name to re-launch her modeling career, after all ‘Dolores Xiques’ was as unpronounceable as ‘Dolores Bichette’ was inaccurate. Despite her father’s disapproval, she opted for ‘Dolores Carlos’ thus honoring her Cuban grandfather, Carlos, whose struggles had inspired her independence.

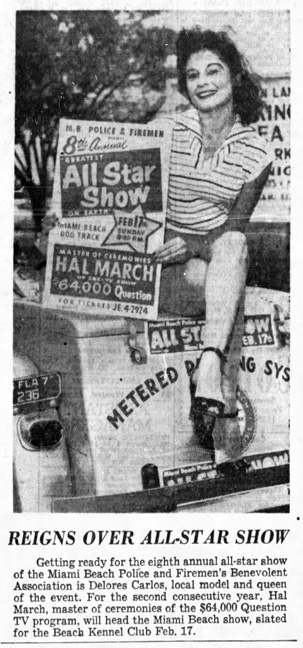

In Miami, her successful modeling resumé from St Petersburg and Tampa opened doors and she found regular work with newspapers and companies like the Roosevelt Theater on Miami Beach. Her modeling career thrived, and she won several more beauty contests, including being chosen as the Miami Beach Police Benevolent Association Queen (even though she picked up a parking ticket from a motorcycle patrolman during the crowning ceremony) and was elected Queen of the Police and Firemen’s Ball held at the Miami Beach Kennel Club.

Finding film work however, which was what she really wanted, was more difficult. Dolores pounded the streets, turning up at every filmmaker’s studio in the southern Florida area. The results? Nada. Tens of auditions came and went without success. Her father suggested she connect with the small community of Cuban filmmakers in Miami – but that yielded nothing either.

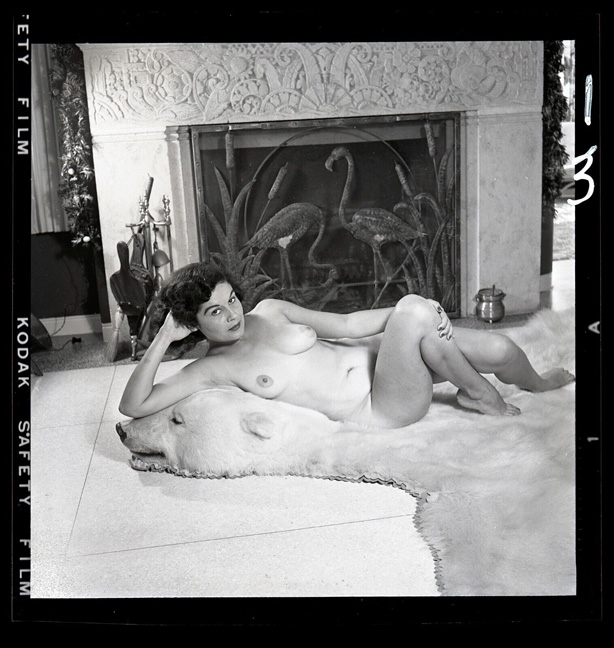

Another type of work was on offer though: pin-up photography for men’s magazines. Typically topless photo shoots, sometime nude, taken on the beaches, by the pools, and in the boudoirs of Miami mansions. Dolores accepted a few of the jobs, but turned most down, fearing salacious photos might kill her film prospects. Besides, she found some of the photographers to be sleazy and predatory.

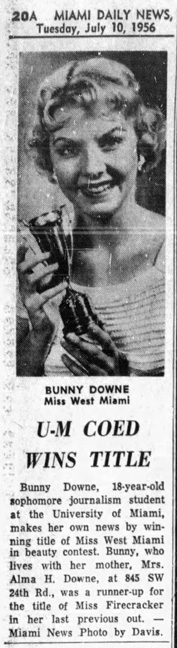

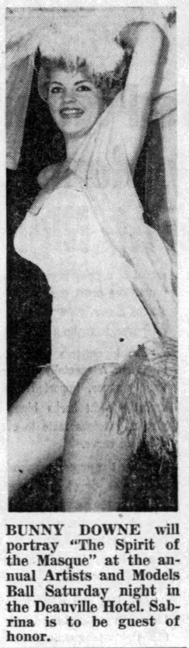

And then she met Louise ‘Bunny’ Downe, a Miami-based model, whose aspirations mirrored her own. Downe was seven years younger than Dolores but was a woman in a hurry: she’d graduated from the local Coral Gables High School in 1955 and enrolled in the University of Miami where, in her sophomore year, she’d had immediate success on the beauty pageant scene, winning the Miss West Miami Beauty Contest, runner up in the Miss Firecracker contest, and competing for the Miss Miami title. By 1957, Downe was working as a model and had set up her own modeling agency. And like Dolores, Downe had married young and unhappily: in Downe’s case, a short-lived relationship with a fellow student that would end in 1959. Dolores and Bunny Downe formed a close friendship that would last for years.

Downe was well-connected and found more modeling work for Bunny, but Dolores had her heart set on movies. In late 1957, with film-work non-existent, Dolores decided to give up and return to St Petersburg. At least there she could see more of Marcy, and she had the promise of weekend modeling work at the St Petersburg Art Studio.

She was approaching 30, and her dream of finding success as a film star was looking less likely by the day.

*

5. Dolores, Doris Wishman, and Hideout/Stakeout in the Sun

In 1957, the same year Dolores was leaving Miami and returning to St Petersburg, another woman in Florida was at a crossroads in her life and she too was considering her options. Doris Wishman was a tiny, energetic, feisty dame in her early 40s, dealing with the premature death of her second husband from a heart attack. She’d been in the film business in New York since the early 1940s when she began working for her cousin, an independent film distributor who handled foreign and independently-produced movies made outside the Hollywood system. Over the next decade, Doris had developed good experience in the distribution business and built an extensive network of contacts with exhibitors.

After her husband’s passing, Doris moved down to Florida to be with relatives, and was looking for an activity that would help her deal with her grief, not to mention an opportunity to make some bucks.

For the first time in her life, Doris decided she wanted to make a film: she had no experience but she’d seen so many low budget films, she figured how hard could it be? Specifically, she was inspired by the success of one film in particular: Garden of Eden (1954), the first film about nudism that had been shot in color. The film was racy and daring in that it showed partial nudity, but it managed to get away with it because the courts had ruled that representations of nudity within the context of nudism could not be considered obscene. Why? Well, because nudism was a lifestyle choice associated with health and fitness, which meant that, by definition, nudists had no prurient interest in nudity. Besides, nudism was considered a serious business at this time: several Florida counties had brought in regulations that required nudists to obtain a permit – and a permit required two character statements from a pastor, priest, or a respectable member of the community. So nudism was wholesome, and the film ‘Garden of Eden’ had been made to capitalize on this – and it worked. Though many court cases were brought against the movie, the producer won most of them and the film benefited from the ensuing publicity and made a big profit.

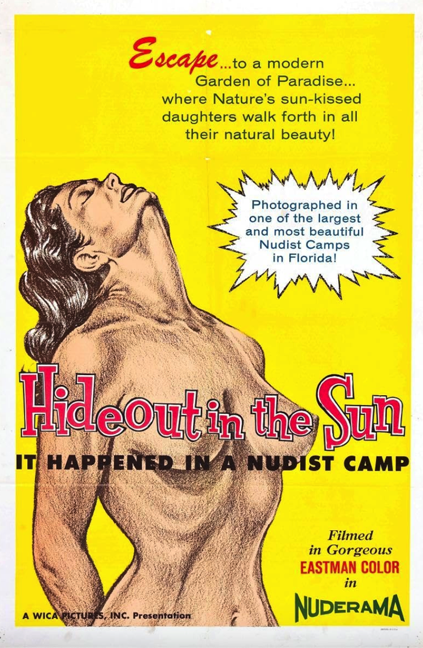

Doris had had a small role in the distribution of ‘Garden of Eden’ so had witnessed the film’s success first-hand. She decided that it provided her with an ideal template. First, to make her own nudist film, she needed money, and she estimated the total budget to be in the region of $10,000. So she raised funds from family members, specifically her sister, and started shooting Hideout in the Sun, in Tampa and Dania in 1957.

So far, so good. But then the problems started. Predictably the first issue Doris encountered was her own inexperience as a filmmaker. The initial footage she shot was too explicit, showing genitals in too much detail for a 1950s film, and so it had to be scrapped. Doris had to start again, so she went back to the same family members and raised another $10,000 for a re-shoot.

*

6. Hideout/Stakeout in the Sun

Summer 1958. Dolores was working at the St Petersburg Art Studio when she got a call from Doris. Doris had heard about Dolores from her friend Bunny Downe’s modeling agency in Miami. Doris and Dolores met up, and Doris offered her the lead role in her nudist film. A friend of Dolores still remembers her initial conflicted reaction: she was excited to be finally offered a role in a feature film, but a little concerned about the nudity – not because of the nudity per se but because of the possible impact that it could have on her daughter Marcy as well as any potential future film work. Dolores eventually accepted – largely because Doris appeared to be less sleazy than some of the other characters that had offered her nude work previously.

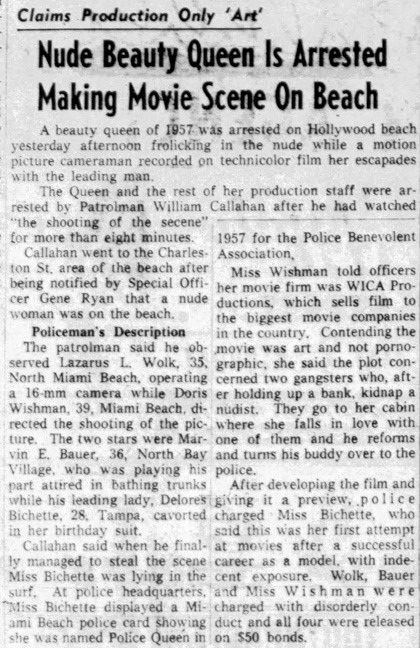

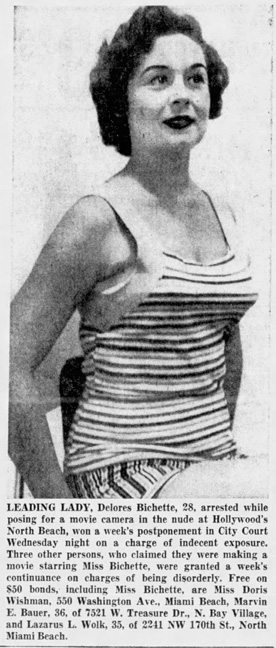

In October 1958, Dolores went down to Miami to shoot footage for ‘Hideout in the Sun.’ One sequence was shot in the sea on a portion of North Miami Beach by Charleston St. There were four people filming that day: there was Doris, Dolores, the cameraman Lazarus (Larry) Wolk (who ended up being credited as the director of the film), and the male lead Marvin Bauer. By day, Bauer was a realtor who had a sneaky sideline renting out his client’s empty houses to pin-up photographers. Bauer, fearful that these clients would hear about his film appearance, would use the name ‘Earl Bauer’ in the film’s credits.

But there was a fifth person there as well that day: William Callahan, a patrolman in the Miami Police Department, who, unbeknownst to the other four, was hiding in the nearby bushes watching the action unfold. In his subsequent report, he described observing the filmmakers for eight minutes. Eight minutes of voyeurism, presumably because he had to make sure he knew exactly what was taking place.

Callahan’s report stated that he saw Dolores “in her birthday suit.” Not just that, but she was “cavorting in her birthday suit.” Callahan’s report elaborated that Dolores was first filmed walking down the beach before writhing in the surf while Bauer looked down on her. After witnessing that, Callahan jumped out of his hiding place and arrested all four of them: Dolores was booked for indecent exposure, the other three for being disorderly. They were all ordered to appear in court the following day. Each of them gave Miami addresses except for Dolores who provided her Tampa home location, and each posted $50 bonds and were released after vigorous protests. Needless to say, the footage Doris shot was confiscated as evidence.

Doris fought back: she insisted that it was a legitimate production on behalf of WICA Productions, who intended to sell the film to “the biggest companies.” She explained that none of it was pornographic, and that the plot was actually about two gangsters who hold up a bank and kidnap a female nudist. The nudist then takes them to her cabin, falls in love with one of them, who reforms, and turns his buddy in. What could be more normal than that, she said?

But whatever public statements Doris was issuing to minimize the event, the newspapers were interested in another part of the story, and they jumped on it like a dog on a dropped steak. What titillated them was evident by their headlines: “Nude Beauty Queen is Arrested Making Movie Scene on Beach” and “’Movie Queen’ Caught Frolicking on Beach” and “Police Eclipse a Rising Star.” One article described how Dolores was picked up “as she lay in the surf, allowing waves to wash over her shapely, unclothed form.”

Dolores had finally achieved her dream of being on the cover of newspapers for being a movie star – it just wasn’t the way she’d always dreamed that it would be. She told the newspapers that it was her first film experience after a long and successful career as a model. She was surprised by the arrest, she said. She told them that the first thing she’d done after the arrest was to show the cops the Miami Beach Police card that she’d been given the previous year when they’d made her the Queen of the local Benevolent Association, but it cut her no slack. The extensive newspaper coverage soon reached her ex-husband and family, and her friends still remembered the ensuing uproar and scandal.

Of course, the cops rushed to develop the footage, and then took a look for themselves. In the end, the accused were found guilty, fined $50 each, and released. It proved a sobering experience for Marvin Bauer, the leading man, who vowed never to do anything connected to nudie films or pin-ups again.

Dolores, however, was surprised by her own reaction: on the one hand, she was a single mother with a successful career as a model who dreamed of being a movie star – but now she’d been arrested for indecent exposure, risked everything she had worked for, and caused a whole mess of embarrassment to her family. And yet, there was something that excited her too. Not so much the sexual side of the story, but more that it provided evidence that she was in some strange way finally independent. She felt seen. And she was going to be in a real movie. Freedom is just another word for nothing left to lose, or something like that. So Dolores doubled down, stepped on the gas, and ignored the rear view mirror.

Most of the rest of the shooting for ‘Hideout’ took place in 1959 in a private residence on one of the islands on the causeway to Miami Beach that doubled as a nudist camp for the film. (The film’s credits claimed it was a genuine nudist camp in order to give the film legitimacy.)

In the years since the film was made, it has been claimed that no genuine nudists actually featured in the film, but in fact, several people cast in ‘Hideout’ were in fact paid-up members of naturist clubs. One was a photographer friend of Dolores, Richard Falcone. Falcone was an Italian property developer, bodybuilder, and part-owner of a nudist colony in Pasco County in Tampa, who’d founded the Sunshine Beach Naturist Club. Falcone had become friends with her when he’d taken modeling pictures of Dolores for her portfolio. He appeared as ‘Dick Falcon’ in ‘Hideout’, and he recruited several of his nudist friends to appear in the film.

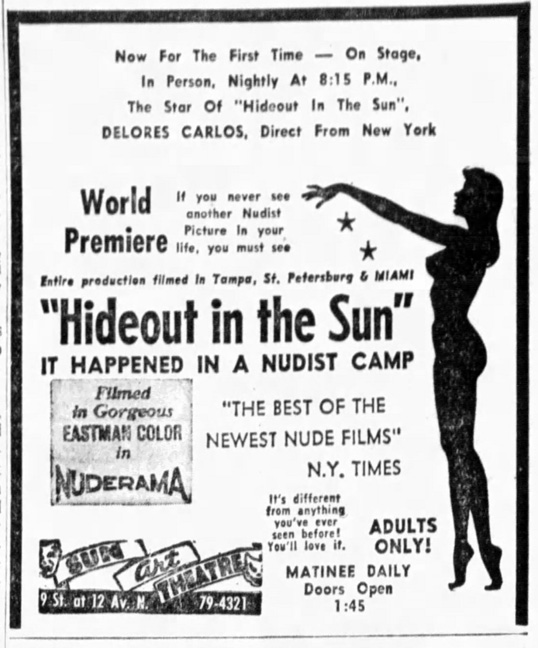

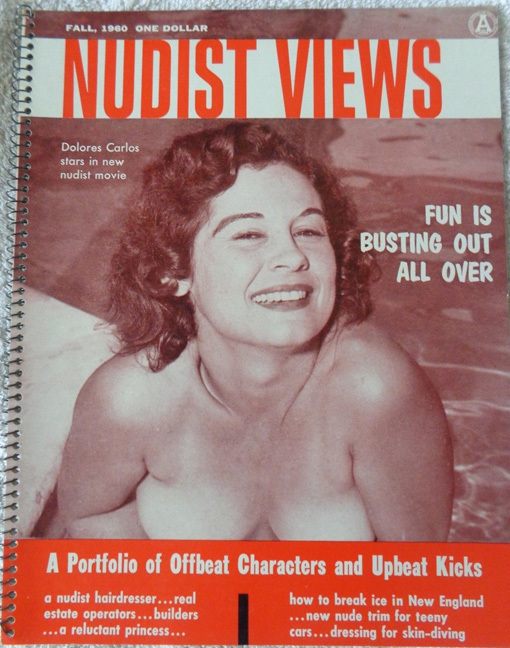

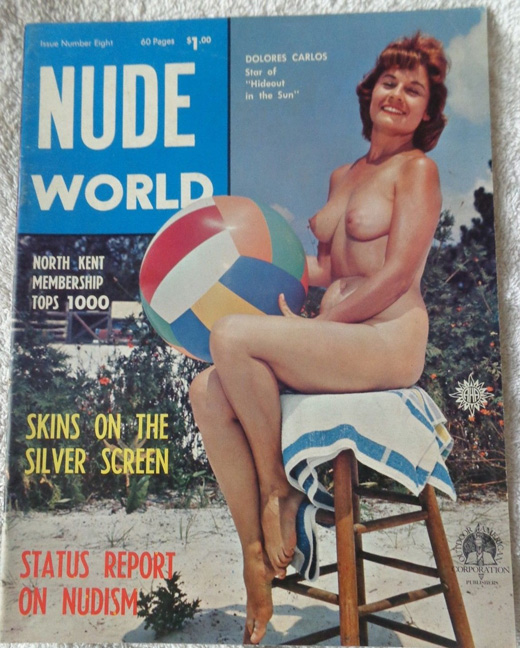

The first public showing of ‘Hideout in the Sun’ took place at the Variety Theater in Miami in January 1960 – advertised as ‘Filmed in Eastman Color and Nuderama.’ The newspaper ads boasted praise from the New York Times (“the best of the newest nude films”) and the invitation that “If you never see another nudist film in your life… you must see ‘Hideout in the Sun.’” Dolores loved the attention which made her feel like a genuine movie star at last, and she made personal appearances to promote it in Miami and then Tampa when the film was released more extensively later in the year.

*

7. Queen of the Nudies

With Dolores spending more time in Miami, she decided – once again – to move south in order to pursue film opportunities arising from ‘Hideout in the Sun.’ She took a small apartment at 1860 NW 1st St in Miami. It was in a rough, undesirable area, but Dolores made friends with the small Cuban ex-pat community and spent most of her spare time down on Calle Ocho or Domino Park in Little Havana, the Miami neighborhood home to many Cuban exiles. Her father was impressed with her new circle of friends and visited her more frequently insisting that they meet and hang out with the Cubanos. Dolores was pleased to finally be where the action was – and exhilarated with the increased interest coming her way.

But soon after, there was another person living with Dolores: Dolores had continued sharing custody of Marcy with Maurice whenever she could, but when Marcy was ten, it became clear that life with her father was not working out as planned so Marcy moved down to Miami and moved in with Dolores. Dolores was over the moon: sure, it made her everyday life more complicated, but she relished the chance to live with her daughter in her small apartment. They both loved the new arrangement. Dolores scheduled her modeling and photo shoots around taking care of her daughter, and Marcy enjoyed living with her glamorous mother. Family members recall Marcy spending hours happily chasing butterflies in the backyard and playing with worms in the ground.

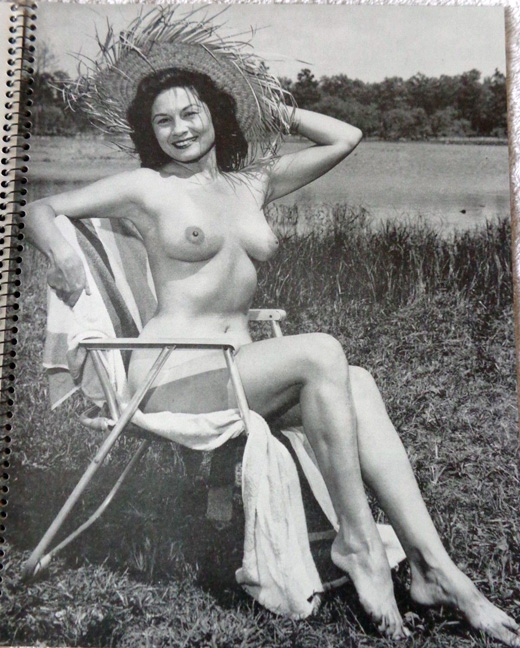

For the first time, money wasn’t a problem for Dolores: magazine work was booming for her, with offers pouring in as she became an unofficial pin-up queen for nudists. She was assisted by her friend, Bunny Downe, who was also cashing in on the up-tick in pin-up work. Starting in June 1960, and then again in August and September 1960, Dolores posed for Bunny Yeager, the Miami-based pin-up photographer who’d worked with Bettie Page in the 1950s.

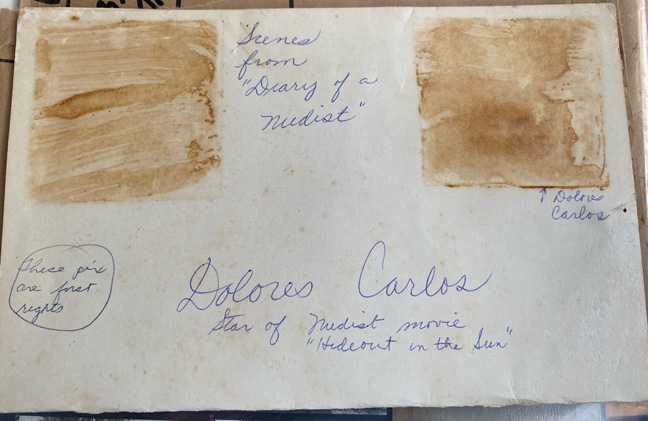

Bunny Yeager’s folder for Dolores

Bunny Yeager’s folder for Dolores

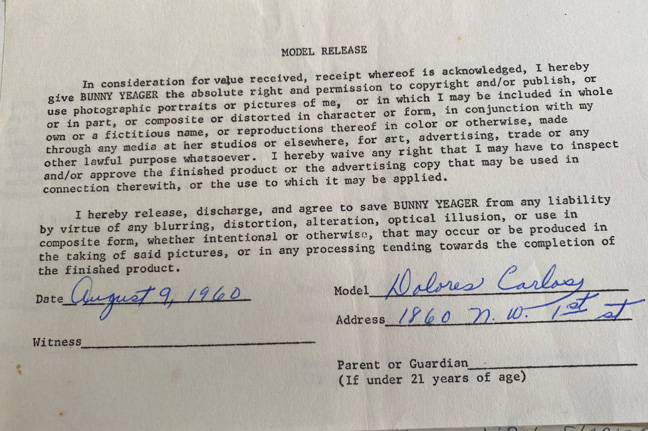

Dolores’ release for Bunny Yeager work

Dolores’ release for Bunny Yeager work

In addition to modeling, Dolores was featuring more regularly in the local newspapers. One report pictured her “atop a snazzy convertible representing one Miami VFW (Veterans of Foreign Wars) outfit in a skin-tight leopard-skin. She is a movie-star in adults-only nudist camp films.” She made a much-anticipated appearance at the Artists and Models Ball where she wore a gown reported as having “only sides – no front or back” and won a trophy for being the “Girl Most Likely to Enslave an Artist.” As a result of her growing celebrity, Dolores was often invited to be a featured guest around town to introduce celebrities on stage when they brought their acts to Miami. These included stars like Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, Dinah Shore, Eddie Fisher, and Jane Russell.

And Dolores was offered more film work – in particular, in nudist films that were suddenly plentiful, cashing in on the success of ‘Hideout in the Sun’. One of the first was in 1961, Pagan Island, when Bunny Yeager assembled a group of models that included Dolores and her friend, Bunny Downe. The film’s director, Barry Mahon, later remembered how Yeager opened doors for him: “A lot of girls wouldn’t do it for a male photographer. (Yeager) was a good photographer alright, but she was getting the best girls simply because the other photographers were all lechers! So I got her to call up all these girls, and that meant I had a real stable of good looking girls out of Playboy magazine.”

After ‘Pagan Island’, there were a couple of Doris Wishman nudie-cutie follow-ups, Diary of a Nudist (1961) and Blaze Starr Goes Nudist (1962), both featuring Dolores and Bunny again – in fact, the two of them would go on to appear in twelve movies together. Ronald Ziegler, a friend of Dolores from her Tampa modeling days, remembered the scene: “Dolores and Bunny were at the center of this new movie-making movement that produced all these topless, nudist camp films. The movies may seem tame by today’s standards, but back then, everyone was getting excited by them – and they made a lot of money. Both girls were pretty, and always had film or modeling work lined up, but their real talent was in connecting people and making things happen. They both had an energy and a desire that didn’t stop – and people gravitated to them.”

Dolores got Ronald Ziegler a role in Doris Wishman’s ‘Diary of a Nudist’ (1961). They had fun so she encouraged him to write a script of his own. As Ziegler remembered, “It was a comedy called ‘Not a Stitch,’ and Dolores and Bunny wanted to produce it. They just needed funding but didn’t know where to turn to. Back in 1961, there was a guy called Silver Dollar Jake who was on the scene. He was a larger-than-life character in Miami, so someone put them in touch with him.”

‘Silver Dollar Jake’, less prosaically born as Jacob Schreiber, was a wealthy, retired Detroit theater owner who lived on Palm Island in Miami Beach. Jake didn’t have much to do when he stopped working so he spent his time driving his outlandishly decorated Cadillac around South Florida, with an eight-inch cigar in his mouth and a pet macaw on his shoulder, promoting causes such as blood drives or the sale of War Bonds. Above all, he liked to flaunt his wealth so he’d throw out silver dollars to passersby.

Ronald Ziegler remembered him well: “Dolores went to see him one day. Jake liked the idea of funding this nudie movie, almost as much as he loved Dolores. He chased her all over town for weeks, and she chased him to get funding. We had meetings and meetings, and it seemed as if Silver Dollar Jake was going to give us all the funding, but when Dolores turned down his romantic advances, his promises came to nothing.” So Ziegler remembers that Dolores and Bunny started again, and pitched their idea to other producers.

One of them was K. Gordon Murray.

*

8. K. Gordon Murray – and the Freedom Tower

Kenneth Gordon Murray was born in Bloomington, Illinois, in 1922. Son of a funeral director, he spent much of his childhood with performers from visiting circus productions who settled in Bloomington for the winter.

Much of Murray’s background is colorful to the point of defying belief: by the age of 20, he’d earned a small fortune by driving the family hearse for local funerals, worked as a casting assistant for MGM where he hired munchkins for ‘The Wizard of Oz’, purchased a decrepit carnival which he renamed ‘United Liberty Shows’ billing himself as ‘The Youngest Show Owner in all of Show Business’, and started a movie theatre construction firm with his father.

In his mid 20s, Murray decided to try his luck in Hollywood working for Cecil B. DeMille on the movie ‘The Greatest Show on Earth’ (1952), but he didn’t adapt well to being a small fish in a big pond so he moved to Miami, Florida, where he formed K. Gordon Murray Productions. After a couple of years of dabbling in low-grade exploitation films (including the re-release of a forgotten 1949 religious epic, ‘The Prince of Peace’), he hit paydirt: in 1959, Murray released an Italian melodrama called Il Momento Più Bello, starring Italian acting legend Marcello Mastroianni. So far, so unremarkable, except that Murray then inserted footage of a doctor hawking sex manuals – and several minutes of grisly, cheaply shot footage showing the birth of twins. (Unsurprisingly, when Mastroianni found out, he sued to have his name removed from the credits.) It was a jarring, exploitative move, but also a highly successful one, aided by an aggressive, salacious promotional campaign. I spoke to a Murray collaborator, Sheldon Schermer, who remembered, “Murray will best be remembered for other films, but make no mistake, this was the one that made him rich. Very rich, in fact. And it wasn’t just the film’s box office: Murray knew the value of merchandise long before other people. He had sex booklets for sale at the refreshment stand in the lobby which people queued up to buy. Whichever direction you looked, he was making money hand over fist.”

By the early 1960s, Murray’s Trans-International Films Inc operated out of impressive offices at 530 Biscayne Blvd, Miami, where Murray had flip-flopped into a new business model: buying children’s movies from Mexico and dubbing them for the domestic market. Gone were the graphic, bloody, baby inserts, now replaced by a string of colorful, surreal fairytale films, like Santa (1960), which became huge money makers.

When Dolores turned up at his office on Biscayne Blvd in 1961 looking for a producer for her nudist movie, Murray was all ears. As his secretary, Veronica Acosta, remembered: “Mr. Murray was always looking for opportunities to distribute movies that weren’t on the radar of the big film companies – and he was well aware of the success of the nudist pictures. Everyone was. And he knew Dolores too as she was on posters and in the newspapers. Despite his big success, Mr. Murray loved that a beautiful woman, like Dolores, had come to him to propose an idea. He liked Dolores, and the feeling was mutual.”

Murray listened to Dolores but explained that he wasn’t ready to finance new movies, rather he preferred to buy existing ones cheaply from other countries. Acosta remembers: “Dolores was persistent and adamant: she told him that the market for nudist films was hot, and that he should take advantage – now!”

In the end, Murray and Dolores struck a compromise of sorts: Murray would re-release a tame five-year-old burlesque film called Naughty New York (1957), which he would rename Eve or the Apple (1962). And to differentiate it from the earlier film, he would shoot an additional nudie insert featuring Dolores and Bunny Downe. The movie premiered in April 1962 at the 79th St Art Theater, where it was billed as “An Intimate, and Slightly Shocking Fun Fest.” The poster claimed, “Bring your seat belts… This one takes off – and we really mean ‘takes off’!”

Dolores and Bunny agreed to tag-team to help promote the film, and the theater arranged for ‘Camera Parties’ to take place in the lobby, where fans could take their own pictures of her (“At 2.30pm and 7.30pm: She appears twice daily in her swimsuit! Take your own pin-ups or have your own picture taken with lovely ‘Eve.’”). Similar events took place when the film played in Tampa and in St Petersburg – this time with Bunny Downe appearing in person. Reviews of Dolores were glowing – “Miss Carlos wears mostly just nail polish,” read one – but despite the salacious publicity, the release was a rare misfire for Murray and made little money.

It was an unsatisfactory outcome for Dolores in the short term, but she was undeterred, convinced that K. Gordon Murray would eventually come good and move into film production, so she stayed friends with him and they continued to meet up regularly. As secretary Veronica Acosta remembered: “Mr. Murray and Dolores were a good match, and there were brief rumors of a romance. He was a friendly extrovert, and she was vivacious and passionate. She was a regular visitor to the offices.”

Acosta also remembered another important detail: “I liked Dolores because, from the beginning, she was the one who started bringing in the Cubans.” The Cubans that Acosta referred to came from the Freedom Tower, an imposing building which, at 600 Biscayne Boulevard, was next door to the offices of K. Gordon Murray Productions. The building was the epicenter for new Cuban immigrants in the United States as it was the central location used by the government to process and document refugees from the Cuban Revolution and to provide medical and dental services for them under President John F. Kennedy’s enactment of the Migration and Refugee Assistance Act of 1962.

At first, Dolores first went to the Freedom Tower in the early 1960s because the building was a convenient stop-off on her way to visit K. Gordon Murray’s offices, but soon it became a regular place for her to go. Dolores had two reasons for going to the Freedom Tower: firstly, she wanted to offer solidarity to her fellow Cuban workers in line with her father’s patriotic wishes, but equally important was that she was looking for film talent freshly arrived in the country. And it worked: she soon befriended a variety of Cuban filmmakers and took many of them to meet Murray where she sung their praises and encouraged him to hire them. As Sheldon Schermer remembered, “These Cuban immigrants would arrive in the U.S., go to the Tower, get registered, and then emerge looking for work. Half of them ended up in Murray’s offices because of Dolores!”

Murray liked what he saw: a substantial number of cheap, experienced, eager-to-work, non-union personnel who could be used on new film projects. Schermer added, “These folks were industrious, creative people: actors, directors, technicians, designers, etc. They were talented, and just wanted to be able to continue their craft outside of their home country where everyday life had become problematic.”

Suddenly Dolores’ small community of friends from the Cuban film industry multiplied as more of them arrived in Miami escaping from Castro’s regime, and Dolores emerged as the center of the group, the person best able to connect them to film productions in the area. It was a far cry from her days as a film-struck teen in a restrictive, old-fashioned Cuban family, and then being a married stay-at-home housewife with a young daughter. She was now in a rare position: a woman who had a career in front of the camera and was well-respected behind the scenes as well.

But Dolores wanted more: acting in films was now her day job, while setting Cubans up with potential employers like K. Gordon Murray was her mission. Men like Manuel Conde, Jose Prieto, and Rafael Remy.

For Dolores her life was finally beginning. She remembered her grandfather repeating a Cuban saying to her: The sun rises for everyone.

*

Next time: the story of one of those Cuban Immigrants.

*

It is staggering to me that The RR takes on topics like this – and greatly appreciated. Rather than being a simple fan site dedicated to the largest breasted star of the 1980s, this goes deep – and covers a person (Dolores Carlos) and a topic (immigrant to the U.S…. ahem….) that no one else would dream of covering. I am excited to see where this new series goes over the next weeks. And thank you.

Thank you so much Nate!

An article like this could ONLY have been done by the Rialto folks. The detail is impressive and I sense it is building into a comprehensive and full overview of an overlooked and underappreciated sector of film: Cubans in Miami.

Tine and again, I have wondered about the sheer number of latino sounding names in the Florida film credits of the 1960s, and wondered what the deal was.

I hope you will be looking at this, as it is an untold topic.

We really appreciate it Jose!

Well done. This is exceptional journalism

Thanks James!

Yet again, TRR casts light on a shaded corner of historicity that deserves exposure. Bravo!

Thank you Elias!

Well, this story struck a chord. Not only because I’m Cuban, and my aunt worked at the Freedom Tower as a nurse helping her fellow Cubans, but because I’m a Miami history buff and many of the places you mention are still around.

the Roosevelt Theater is on 41st Street in Miami Beach. It has been closed for many years now, waiting another chance to show movies.

You mention the Variety Theater and give the address as 550 Washington Avenue. That’s the Paris Theater. It doubles as a nightclub these days.

I enjoyed your story and am looking forward to its next chapter. Thank you!

Thank you so much for sharing your memories Andres!

I’m dying here, RR. Beyond fascinating!

Awww – thanks JWP!

I stumbled upon this podcast after listening to the Once Upon a Time in the Valley. Being a completist, I started at the beginning with episode 1. I’m just finishing up episode 100 today and feel compelled to tell you how much I enjoy the show. Every story is fascinating- sometimes funny, sometimes tragic, but always informative. I often start a podcast , listen to 10-20 episodes, then move on. After hitting the century mark, I must tell you TRR is now my go-to show. True journalistic excellence on a little explored subject that deserves attention.

We so appreciate this David – thank you for listening!

I never knew her son was the baseball player Dante Bichette.

Wonderful and thanks so much! I wish you’d posted a picture of what she looks like now. I think former starlets are so pretty when they get older.

Gorgeous production, on a scarcely known aspect of this mysterious world. Grateful for your sublime work, and ecstatic for more! Thank y’all

🕊❤

This series is gonna be the dog’s gonads, i can tell. Much thanks for filling this gap