Harold Kovner. Maybe not the sexiest name in the history of the golden age of adult film. In fact, you may never have heard of him.

But wait.

The story of this mysterious New York sex film director involves tales of World War II heroics, German Expressionist cinema, RKO Pictures, Orson Welles, left-wing political activism, legendary ballet choreographer George Balanchine, the birth of network television, Broadway burlesk shows, Elizabeth Taylor’s husband Mike Todd, obscenity busts, adult films on the east and west coasts, landmark court rulings, money laundering for the mob, allegations of mafia involvement in child pornography, and much more.

Anything else?

Well, there’s the small matter of a divorce case heard in the New York Supreme Court – where a husband alleged that he’d gone to a Times Square grindhouse and noticed his wife on-screen having sex in an explicit pornographic film. Awkward.

In other words, it’s a typical Rialto Report story, with diversions, tangents, and the surprising lives of supporting characters spanning different continents, eras, and personalities.

The Rialto Report extends sincere thanks to the many family members, friends, and associates of those featured in this story for sharing their extensive memories and documents over the course of many year’s research. Thanks too to Joe Rubin of the inestimable Vinegar Syndrome.

——————————————————————————————————————————————

On his business card, he was billed as an audio engineer. On his tax forms, he was termed a sound technician. As for himself, he had his own self-description: it was based on the thousands of hours he spent working with audio tape. He called himself Mr. Rewind/Fast Forward.

But in truth, whatever his nickname, if you passed him in the street, would you even notice another downtrodden, downtown man? Why should you? Just another New Yorker with an average life and a mundane past, right? Move on, nothing to see here.

*

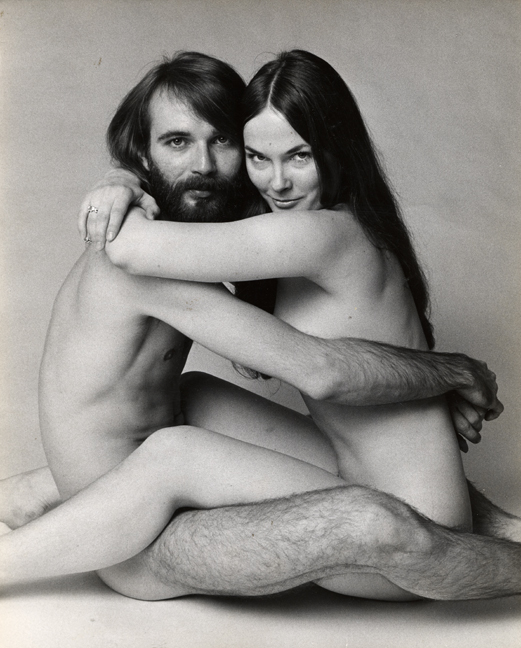

January 1973 – Harold

Harold Kovner rose early, put on his best suit, and tried to remember the day he’d first met her in a lower Manhattan massage parlor. A brothel to be more precise, or a whorehouse to be more honest.

His memory of their initial encounter was hazy. According to his diary, it had been a late afternoon eighteen months earlier in June 1971 when he entered the unmarked establishment down on Fulton Street and asked the chain-smoking madame to see the prettiest dark-haired girl in the place. He was ushered into a back room, furnished only with a bed and two coat hangers, to wait for her.

When the requested dark-haired girl appeared and sat on the bed next to him, she inquired what he was in the mood for.

Harold pivoted. “Ever thought about being an actress?”

“Sure, which girl doesn’t?” she replied flatly.

Harold said he was serious. He was casting a low budget film and had a speaking part for a girl like her. Some sex too, but he didn’t imagine that’d be much of a problem.

“Who do I have to ball?” she asked.

Harold told her that he had a good-looking young guy lined up.

“As long as you’re paying me, I guess I can do it,” said the dark-haired girl, “just no kissing, ok?”

Harold pulled out a business card: ‘Kovner – Sound Engineer – 76 Franklin Street. 539-7294.’ He told her to call him later in the week. They shook on it, and the dark-haired girl giggled.

“I’m Jean Roman,” she said.

*

January 1972 – Abraham

No one knew how Abraham Rosenzweig found out about the pornographic film.

Friends agreed he wasn’t the type to frequent the Times Square grindhouses where the recent craze of explicit hardcore features were released into the city. Rather, he was a respectable corporate personnel executive, residing in an elegant apartment complex next to the Dakota building on the Upper West Side of Manhattan.

But someone must have told him, because, in January 1972, Abraham called his office to say he was sick and set off to Chelly Wilson’s Cameo Art theater on Eight Avenue (the ‘Art’ was wishful thinking). He was there to see a new XXX film release entitled A Time To Love and had selected an early afternoon screening to avoid the remote possibility of bumping into any acquaintance. He arrived early, sank deep into a seat close to the exit, and watched an adult film for the first time.

The movie was a tale of two former college buddies who reunite and compare their lives. It was an earnest, pedestrian effort, and whoever the filmmaker was didn’t appear to be overly interested in the sex. After half an hour of dark fumblings on the screen, Abraham was beginning to regret his afternoon visit.

And then it happened.

A scene in a bar. The morose male lead spots a woman in an elegant evening dress. He lights her cigarette.

“Couldn’t be as bad as all that,” she opens with a reassuring tone.

They chat and then leave to go to her place where she cooks for him. And then they have sex in explicit detail. The sequence lasts for just fifteen minutes. Abraham watched with a sick feeling in his stomach.

It was unmistakable. It was his wife onscreen.

*

January 1973 – Harold

It was snowing when Harold Kovner set off from his apartment and work studio at 76 Franklin Street to walk the ten minutes to the County Courthouse at 60 Centre Street, home of the New York State Supreme Court.

He was a large, paunchy man in his mid 50s. He colored his thick crop of hair jet black to look younger, but it merely accentuated the dark age rings under his eyes. Years earlier, he’d roamed the streets of lower Manhattan, but nowadays walking anywhere just increased his irritability, and he was already grumpy today. The last place he wanted to be was a courthouse.

The summons had arrived the previous Friday when he was leaving his job at Barclay-Crocker, an audio tape duplication company. It came in the form of two private investigators who accosted him as he left the office building at 11 Broadway. They muscled him into nearby Bowling Green Park, and thrust photos of a young woman in front of him.

Did he recognize her, they asked? Who wants to know, Harold replied?

Harold was a calm person but this approach made him nervous. For the previous 18 months, New York had been one of the nation’s epicenters for a national debate on obscenity in films. For politicians, attorneys, councilmen, even Supreme Court justices, this was a chance to display their indignation at the rising tide of filth appearing across the country, and they relished the possibility to brandish their moral arguments. But for anyone involved in making movies with any sexual content, it was a time of uncertainty and fear.

The heavies persisted. Did this woman feature in a hardcore sex film that Harold had shot?

Harold figured he was about to be busted for the sex films he’d made, and the prospect of years behind bars suddenly loomed in front of him. He silently cursed using his real name in some of the film’s credits.

He protested, insisting his films were not obscene in any way.

The investigators laughed. They had no interest in his film, they said. Their mission was just to confirm the identity of woman in the photographs. Was she the same person as the actress in one of Harold’s movies?

They explained: a fifteen-minute sequence of a pornographic film had been shown on a temporary screen in divorce court earlier that day. It featured a woman remarkably similar to the woman contesting the divorce. The trouble was this broad testified in court that it was a case of mistaken identity. No way was that her up on the screen performing sex acts that were causing the court gallery to blush, she insisted.

Harold relaxed a little. “I don’t know. It could be her, I guess. I’m not sure,” he said.

“We’re gonna need you to appear in court next Tuesday as a witness,” came the demand.

*

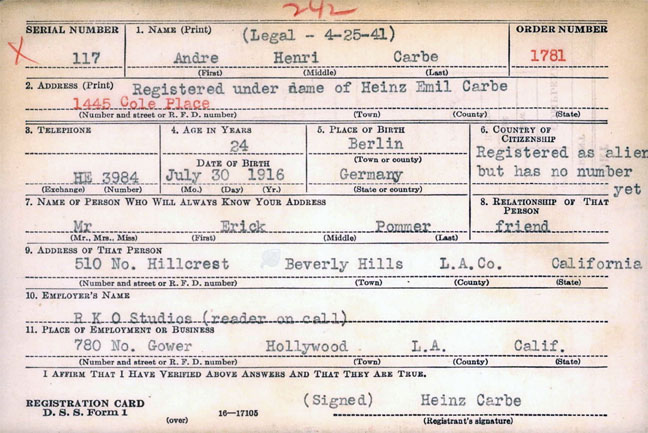

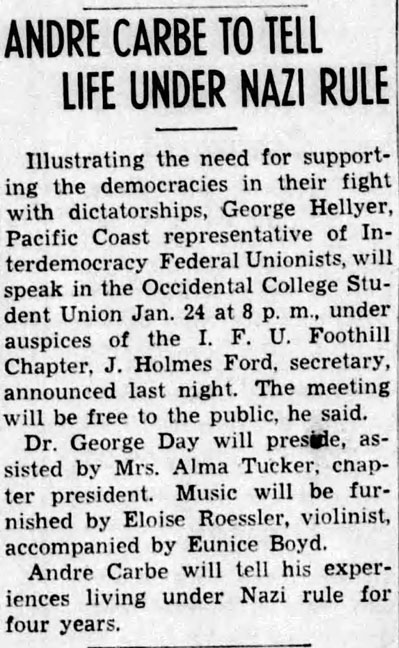

1940 – Harold, and Varian Fry

Harold was an unlikely pornographer. His life began in the Bronx in 1916. His parents, married in 1909, were Eastern European Jewish immigrants: his father Jacob Kovner, known to all as Jack, had arrived from Russia, and his mother, Ida Umansky, hailed from Poland. Jack was a dentist, and Harold, together with his brother and two sisters, enjoyed a comfortable family upbringing in a household that included a live-in maid. Despite the middle class trappings, Harold’s parents were left-leaning Socialists and raised their children with an ever-present emphasis on social issues and the plight of the have-nots. The family took politics seriously, attending rallies and involved in activism for various human rights causes.

After leaving school, Harold worked briefly for a succession of newsreel companies, notably Hearst Metrotone and Pathé News, but his first love was audio recording and broadcasting, and so he took a job at FADA Inc, an influential radio manufacturer. FADA had been founded in New York by Frank Angelo D’Andrea (aka F.A.D.A.) in 1920 and soon became famous producing a line of popular ‘bullet’ radios known for their colorful plastic casing. In 1937, FADA moved into television production, presenting their first television model at the New York World’s Fair of 1939. Harold was intimately involved in the development of both the company’s radio and television models and developed an expertise in audio technology that was in demand in a growing industry.

FADA 115 Bullet radio, circa 1940

FADA 115 Bullet radio, circa 1940

Work at FADA kept him busy, but what occupied him even more was his political activity as a young Socialist. The economic hardship of the Great Depression had offered Socialists a clear opportunity to present an alternative to capitalism, attracting new members and invigorating political activity. In New York in the 1930s, Socialism was an immersive political culture with tight-knit networks where friends, neighbors, and even local business owners shared similar political beliefs. This was particularly true in neighborhoods like the Lower East Side, the Bronx, and Greenwich Village, where radical ideas thrived.

Harold threw himself into the fray, a robust, barrel-chested spark-plug, becoming a member of the American Labor Party (ALP) and the Socialist Party of America, actively involved in organizing protests, and frequently in conflict with the police and other political factions. He was virulently anti-Nazi, acutely focused on the rising threat of Nazi Germany, and he attended rallies across the city to highlight its menace. At one event in 1939, he met and befriended a fellow activist, Varian Fry.

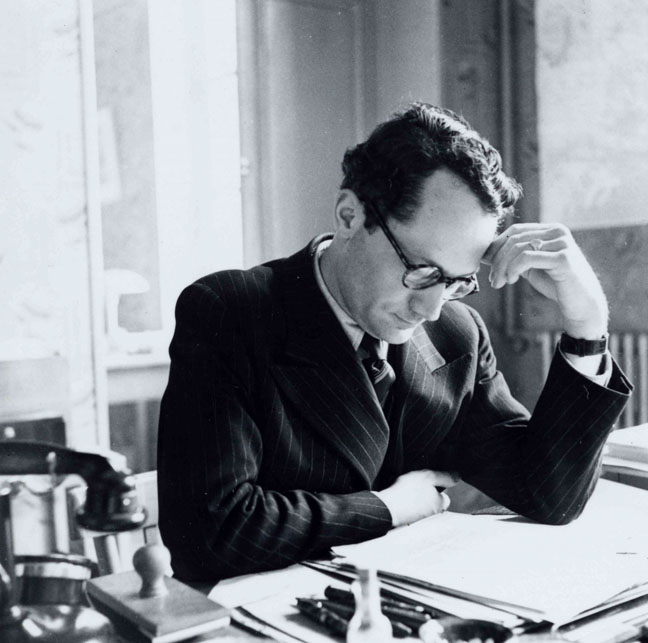

Varian, a son of wealthy stockbrokers – bespectacled, with a young Henry Kissinger-like appearance – was brilliant and worldly. He had led a different life from Harold and, on the surface, it was an incongruous friendship. Varian was ten years older than Harold, married though closeted-gay, and while Harold was still living in the family’s Bronx apartment with his mother, Varian had his own place from where he wrote political articles and organized his own activism. The two bonded on a political level – Varian was equally committed to anti-Nazi activity – and they became inseparable as they crisscrossed the city taking part in political events and fund-raisers.

In June 1940, they attended a political meeting together at the Commodore Hotel in New York. The gathering would have a momentous effect on the war effort, and on Varian’s life in particular.

*

Rewind – Varian Fry

Varian Fry was an exceptionally smart man. Everyone knew that. After graduating high school fluent in several languages, he had headed for Harvard University having achieved one of the highest scores on the 1926 entrance exams. His first love was journalism and at Harvard he founded ‘Hound & Horn’, an influential literary quarterly that featured contributions from Gertrude Stein as well as future Pulitzer Prize winners Katherine Ann Porter and Elizabeth Bishop.

After graduation, he took a job as a foreign correspondent for the journal ‘The Living Age’, visiting Berlin in 1935. It was a life-changing moment: witnessing the extent of anti-semitic abuses, he became an ardent anti-Nazi and vowed to dedicate himself to fighting back. Upon his return the U.S., Varian wrote articles in The New York Times about his experiences, and published a series of books analysing foreign events in the lead up to World War II. But it didn’t feel enough, and he felt compelled to do more to fight the scourge of fascism: “I could not remain idle as long as I had any chances at all of saving even a few of its intended victims,” he remembered later.

*

1940–1941 – Varian Fry

Varian’s chance came on June 25, 1940, when he attended the meeting at the Hotel Commodore in New York City with Harold. The gathering brought together 200 prominent people to figure out a solution for the Jewish refugees trapped in German-occupied France.

Earlier that month, Nazi Germany had defeated the French army resulting in the occupation of the northern half of France. The southern half, termed ‘Vichy France’, remained nominally independent. As a result, tens of thousands of refugees from Nazi Germany, and many others from elsewhere, fled to Vichy France, hoping it would be a safer haven, with most ending up in Marseilles. The hope was illusory: the Vichy regime was under an obligation to “surrender upon demand” all German citizens to the Gestapo.

The objective of the Hotel Commodore meeting was to identify a way to find escape routes for the Jewish refugees who’d become trapped in southern France, with an emphasis on rescuing the elite intellectuals and artists. The meeting resulted in the founding of the Emergency Rescue Committee (ERC) which was funded by an immediate $3,500 in contributions. The only problem? The newly formed group needed an agent on the ground in Marseilles to execute the covert operation under the nose of the German Gestapo. It was a dangerous proposition: one of the ERC founders admitted, “Send someone to France, and he’s dead.” Undeterred, Varian volunteered for the lone wolf role, and was accepted.

In August 1940, Varian arrived in Marseilles with $3,000 taped to his leg and a list of 200 artists and intellectuals, mostly German Jews, who were under imminent threat of arrest by the Gestapo. His job was to locate them and find ways of secretly getting them out of the country thereby circumventing the bureaucratic processes set up by the Vichy authorities who refused to issue exit visas. After Varian arrived in the city, he was contacted by more anti-Nazi writers, avant-garde artists, musicians, and hundreds of others, all desperately seeking to escape France.

Varian got to work immediately, and his methods were as effective as they were unconventional: in one instance, he accompanied a group of refugees on smugglers’ foot trails across the Pyrenees to gain illegal entry into Spain, before secretly transporting them to Lisbon from where he arranged safe travel to the U.S. Time and again he arranged safe passage for refugees using his guile and cunning in the face of constant danger.

It was a bold, high-risk operation: in Marseilles, Varian was pursued by the Gestapo who were rounding up and imprisoning Jewish refugees, but also by the Vichy authorities who claimed that his activity was illegal. To make matters worse, Varian was largely unsupported by and unpopular in his own country: the U.S. was still neutral in the war, and its priority was not facilitating the emigration of refugees to the U.S. (one diplomatic cable read: “The Government cannot – repeat, not – countenance the activities of Mr. Varian Fry in carrying on activities evading the laws of the countries with which the United States maintains friendly relations.”) This reflected American sentiment: opinion polls showed that only 21% of Americans wanted more Jewish immigrants to be admitted to their country. Fry was also shunned by most of the refugee aid organizations in Vichy France who regarded him as a threat to their programs. To Fry, these agencies were failing to recognize the gravity of the situation, and he was contemptuous of their lukewarm efforts. And then there was his own organization: Varian came under fire from the ERC who became wary of his unpopularity within the U.S. government.

Under fire from all side, it was a near-impossible situation, and in early 1941, the ERC ordered Varian back to the U.S. He refused, and continued his work, funded in part by a close friend, Chicago heiress Mary Jayne Gold, who financed many ERC operations. Despite the resistance to his activities, Varian’s bold and high-risk refugee-smuggling operation continued to be a resounding and undeniable success. It is estimated that in just over a year, he saved the lives of over 2,000 artists, scientists, and inventors from Nazi-occupied Europe, among them artists Marc Chagall and Max Ernst, writer André Breton, and philosopher Hannah Arendt.

The fierce opposition to his activities eventually won out, and in September 1941, Varian was forced to leave France after officials of both the Vichy government and the U.S. State Department formally objected to his covert activities.

Back in the U.S., Varian continued to speak out critically against the country’s immigration policies – particularly relating to the fate of Jews in Europe (in an issue of The New Republic, he wrote a scathing article titled: ‘The Massacre of Jews in Europe’) – and in January 1942, the ERC fired him outright: “Unfortunately your attitude since returning to this country has made it inadvisable for us to continue your connection with the Committee,” read the dismissal letter.

*

1946 – Harold and Varian, and Andre Carbe

After Varian returned to New York, he met up with Harold for an emotional reunion at the White Horse Tavern in the Village. Harold had left his job at FADA in October 1940 when he’d been drafted to the war effort to work in radio services (FADA, like every similar manufacturer, had suspended its consumer TV and radio production as World War II began).

Their friendship resumed immediately, though Harold saw that the wartime experience had changed Varian. Varian’s intelligence and insight remained, but the optimism, energy, and hope seemed dimmed, replaced by a nervousness that bordered on paranoia.

In 1945, Varian wrote an autobiographical account of his time in France, ‘Surrender on Demand’. It sold well, and at the end of the war, he was recruited to provide guidance to the FDR government. By now, he was well-connected: a member of the Harvard Club, part of the Council on Foreign Relations, member of the board of directors of the International League for the Rights of Man and the American Civil Liberties Union, and director of the Department of Foreign Policy.

At the same time, Harold was thinking about his future. After his work at FADA, he considered himself to be a sound engineer but was entertained a move into the film world which he predicted would be a major growth area after the war. Despite having minimal experience, he started making short films for a variety of corporate clients. He was social, popular and garrulous, adept at befriending and impressing notable figures in the business world, and he picked up sufficient film work to keep himself afloat. One acquaintance was George Balanchine, co-founder of the New York City Ballet, whose minimalist staging style appealed to Harold’s socialist aesthetic. Harold offered to work with Balanchine to create short films showcasing some of the choreographer’s work, and Balanchine was reportedly impressed with the results.

In 1945, Harold suggested to Varian that they form a business to produce 16mm sound motion pictures and recordings on disc and film. Varian had no experience in the field, but was looking for a new challenge. He liked the idea, and secured funding of $60,000 from his contacts, notably Mary Jayne Gold, the heiress who had financed part of his covert operation in Marseilles. Most of the new investment was used to purchase film and recording equipment for the business.

They called their company Cinemart, and opened offices at 565 Fifth Avenue, initially specializing in creating motion-picture records of ballet, dance, and theater productions. Harold’s skill in recording techniques also created business opportunities making disc recordings for corporate and education entities.

Harold worked hard but the volume of incoming business was slow. Part of the problem was Varian’s lack of expertise in the film business, but there was a bigger issue: Varian was struggling to find meaning in his new post-war life. He stretched himself thinly, taking on work as a journalist, magazine editor, and college lecturer. His mental health was suffering and with it his physical state. He struggled with his own homosexuality and he got divorced shortly after he returned from France. He married again, this time to a woman 16 years his junior.

Harold convinced Varian that they needed to recruit someone with greater expertise. In 1946, they announced the appointment of Andre Carbe as Executive Director in charge of Production.

*

Rewind – Andre Carbe

On paper, Andre was a good fit for Cinemart.

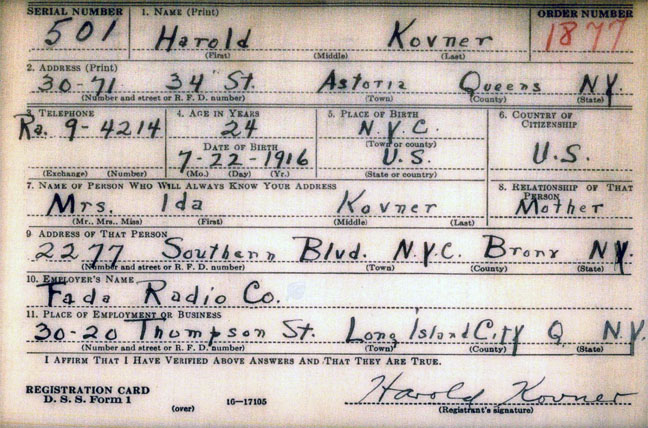

He was born Heinz Emil Carbe in Berlin in 1916, the jet-black-haired, handsome son of a Jewish newspaper magnate. After an early education in France and England, in the 1930s he’d gone to work in Paris for German-born film producer, Erich Pommer.

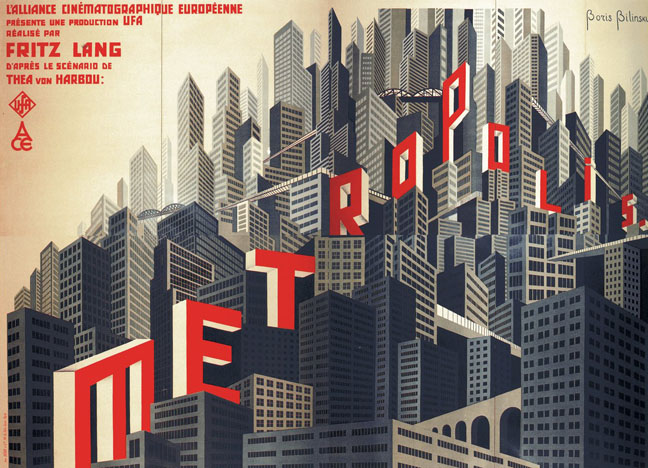

Pommer was the most powerful person in the German and European film industries in the 1920s and early 1930s, involved in the German Expressionist movie movement during the silent era, responsible for many of the best-known films of the Weimar Republic such as ‘The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari’ (1920), ‘Manon Lescaut’ (1926), ‘Faust’ (1926), ‘Metropolis’ (1927) and ‘The Blue Angel’ (1930).

Pommer was almost thirty years older than Heinz and he took the kid under his wing as a surrogate son. He recognized that Andre had talent, energy, and ambition, but also that the younger man was a restless young playboy who was prone to bouts of self-doubt and depression. Pommer nurtured Heinz, finding him jobs working for Fox’s subsidiary in London, British Movietone News, the first sound newsreel distributed in the country, as well as small production roles on various successful movies, including ‘The Private Life of Henry VIII’ (1933). It was an impressive film apprenticeship.

Part of Heinz’s volatile mental state could be attributed to his political views. His newspaper-owning family in Germany was under pressure to align their reporting to the fascist priorities of the government. Heinz was vocal about the dangers of National Socialism and used his privileged position to speak out across the continent – which attracted negative attention from the authorities in Germany. His mentor, Erich Pommer, moved to Hollywood after being forced to flee Germany due to the purging of Jews from the film industry in July 1933 after the Nazis came to power.

Pommer was concerned about Heinz’s safety, not to mention his mental well-being, so he encouraged Heinz to change his name and relocate to Los Angeles. Heinz obliged and moved into Pommer’s California home – where he was described by the Los Angeles Evening Citizen News as “Europe’s youngest film producer.’ Heinz, now calling himself by the more Francophone name Andre Henri Carbe, set up his own company, Atlas Pictures, Inc. and announced his intention to produce plays and make “a series of unusual short subjects.” Gossip columns covered details of his romantic conquests, which included Joanne Woodbury, future star of Charlie Chan films and Roy Rogers Westerns. Andre’s anti-Nazi activism continued and he gave regular talks about life under Nazi rule across California. Fearing that he may never be able to return to Germany, Pommer sponsored Andre’s U.S. citizenship in 1937.

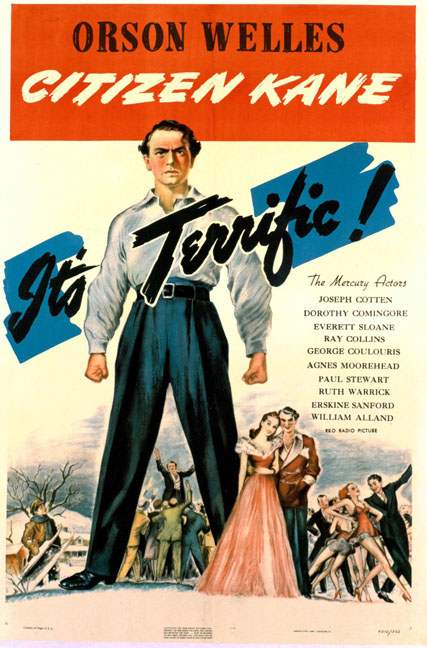

Pommer also got Andre a job as an assistant director and writer at RKO Pictures. It was a coveted deal: the studio had hit big with ‘King Kong’ (1933), and was now renowned for its cycle of successful musicals starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, as well as for giving stars like Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant their first major triumphs. At the time, RKO was in the process of trying to lure Orson Welles to Hollywood, and Andre was drafted to the negotiating team to persuade the reluctant director to bring his vision to the studio. Andre became friends with Welles during the process. It was a successful pitch, and Welles signed a contract with RKO in 1939.

In 1940, Andre’s career momentum was slowed when he was drafted into the U.S. Army serving the Signal Corps and Military Intelligence Service stationed in New Jersey. While in the army, he worked as a film editor, wrote a screenplay about conscription, and was briefly posted to Munich where he secretly served as the editor of the Army’s World-in-Film Newsreel.

Andre’s conscription card, with Erick (sic) Pommer shown as next of kin

Andre’s conscription card, with Erick (sic) Pommer shown as next of kin

In the army, Andre also befriended a fellow aspiring and ambitious film producer, Ely Landau, and it was at a 1943 meeting of the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee (JAFRC) in New York, a coalition of communists and pacifists concerned about the rise of Fascism in Europe, that Andre and Ely met and befriended two like-minded activists and film enthusiasts, Harold Kovner and Varian Fry.

*

1946 – Cinemart

When Cinemart started encountering difficulties, Harold was keen to attract both Andre Carbe and Ely Landau to join the company. Landau declined as he was more interested in working in television, but Andre joined Cinemart in October 1946 where he took charge of production – with an initial remit to produce a series of documentary films on social issues. Varian was the public face of the company, and Harold continued to work on audio productions, as well as concert and ballroom dance shorts for theatrical and non-theatrical distribution. Together they became known as the ‘Three Musketeers’ by their associates and clients in the film world: the combination of a former RKO Pictures filmmaker, a well-known war hero, and an experienced audio and sound engineer – all well-financed by trusting benefactors – promised to be an attractive commercial proposition, and early signs were positive.

During his time in Los Angeles, Andre had developed friendships with Hollywood heavyweights such as John Ford, Howard Hawks, and Orson Welles, yielding business opportunities for the company. Welles, who had gone on to success at RKO with ‘Citizen Kane’ (1941) and ‘The Magnificent Ambersons’ (1942), visited the Cinemart studio frequently and spent time exchanging ideas with the team. He was a vocal lifelong progressive and anti-fascist whose political activism was deeply intertwined with his artistic work, and he struck up a particular friendship with Harold. Welles invited Harold to Toots Shor’s Restaurant at 51 West 51st Street in Manhattan, and for the next few years, whenever Welles was in town, they had a semi-regular appointment there, discussing politics, film, business, and audio recording techniques. Occasionally they were joined by other celebrities such as Joe DiMaggio, Jackie Gleason, and Ernest Hemingway. Harold enjoyed his association with Welles and would speak about it for years after.

Politics continued to be important for the three owners of Cinemart, and together they were regulars at town hall meetings, marches, and fund-raising events. It sometimes resulted in skirmishes with the authorities – especially for Harold and Andre. The two weren’t ones to start physical confrontations but they didn’t run away from conflict either, and the excitement of their joint cause bonded them closely. On one occasion in 1949, Harold and Andre went to Cortlandt Manor, a town near Peekskill, New York, for a concert featuring actor and singer, Paul Robeson, known for his strong support of left-wing causes and civil rights. They were met by a mob of protestors, which included American Legion members and Ku Klux Klan sympathizers, chanting racist and anti-Semitic slogans. A burning cross was placed on a nearby hill as the mob threw rocks and attacked attendees, forcing the concert to be canceled and injuring over a dozen people. Harold and Andre returned a week later when the concert was rescheduled, but despite the show proceeding peacefully, they were again attacked by a violent mob afterwards who again threw rocks at exiting cars and buses, injuring about 140 people. Harold and Andre engaged in a running battle with their attackers and Harold was struck in the head, requiring stitches. Police did little to intervene, and some were even suspected of participating in the aggression. The events came to be known as the Peekskill riots. Harold joked that it was his generation’s Woodstock.

Meanwhile the Cinemart re-launch proceeded with articles in trade publications advertising the company’s offerings as “complete commercial productions, fashion shows, tele-commercials, sound studio facilities (disc, tape, film).” Harold spoke with family and friends about his hopes of creating a successful independent film enterprise. They moved to larger offices at 9 East 46th Street, as well as a new studio at 101 Park Avenue, and in 1947, Harold renewed his association with George Balanchine producing a full length, 16mm, sound production of Ballet Russes’ ‘Danses Concertantes’, their first complete color film with sound.

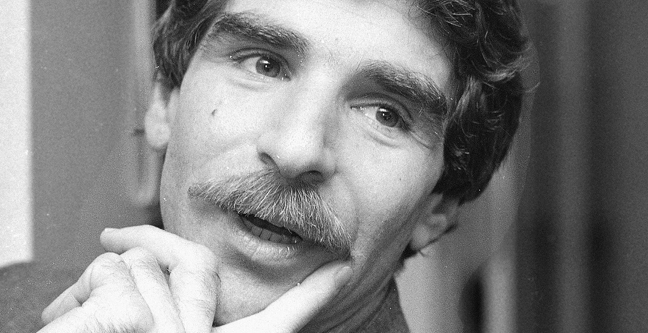

Andre Carbe (second from right)

Andre Carbe (second from right)

It was all set up for success, but Cinemart struggled to win new business. It was perplexing given their contacts, but the Three Musketeers were in little doubt as to one reason for their difficulties: they were being blackballed for their political beliefs. Anti-socialist sentiment had intensified in the country in the post war years, creating a climate of widespread fear and suspicion against anyone perceived as a communist or radical. While the most severe purges occurred in the 1950s with McCarthyism and the Red Scare, the foundation was laid in the late 1940s through federal loyalty programs and investigations. In New York, many labor unions, once home to socialist organizers, began to expel leftists under pressure from anti-communist forces. Cinemart, well-known for its left-leaning management team, suffered in a similar way. New business started to dry up, film contracts that had been promised to them failed to materialize, and their funds in the bank ran low.

The three friends remained tight, but Harold could see that Varian and Andre took Cinemart’s difficulties personally, exacerbating their sometimes-fragile mental states. Both became less reliable and contributed less to the business. For a time, he carried both of his friends, working diligently around the clock to keep the money coming in, but he needed to take care of his own future. He started to take work making films outside of Cinemart, and in May 1951, the company filed for bankruptcy under Chapter 11. Erich Pommer, always sensitive to the threat of right wing actions in shutting down careers and businesses, offered funds to keep the company alive.

Cinemart limped on for another year but was shuttered permanently in the early 1950s.

*

Fast Forward – Varian Fry

After the demise of Cinemart, Harold stayed friends with both Varian and Andre.

Varian returned to working as a writer, but his post-war PTSD and mental health issues continued: he felt increasingly troubled by the lack of recognition for his wartime efforts. He struggled to adjust to civilian life and moved between jobs, including working as a Latin teacher at a boys’ school. He grew more troubled, reportedly exhibiting irrational behavior believed to be the result of manic depression, and went into psychoanalysis to deal with it. His second marriage broke up, and in 1967, living in relative obscurity, he was found dead of a cerebral hemorrhage. He was buried at Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York with his parents, with only brief mentions of his passing in the media. Harold attended Varian’s memorial, describing him as “the best friend a man could have.”

As time passed, Varian’s wartime heroics became more widely acknowledged, and he was the first of five Americans to be recognized as “Righteous Among the Nations”, an honorific given by the State of Israel to non-Jews who saved the lives of many Jews and anti-Nazi refugees during World War II.

A film was made of his life, Varian’s War: The Forgotten Hero (2001), which starred William Hurt as Varian.

In 2023, a Netflix TV series dramatization called ‘Transatlantic’ told the story of Varian and the Emergency Rescue Committee. Cory Michael Smith starred as Varian, and Gillian Jacobs as the future Cinemart investor, Mary Jayne Gold.

In 2000, a square in front of the U.S. Consulate in Marseille was named ‘Place Varian Fry’ in his honor.

*

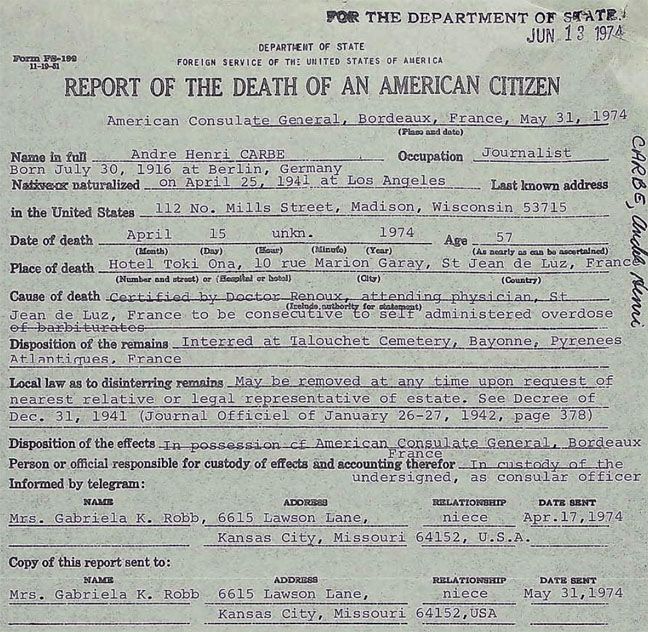

Fast Forward – Andre Carbe

After the war, Andre became a documentary filmmaker for public broadcasting stations, occasionally helping out with New York feature films (he was the assistant director on ‘Johnny Gunman’ (1957)). His work often focused on issue-driven causes and social justice, but the work was sporadic, and in lean times, he found work as a window dresser for retail stores or volunteering for the American Labor Party.

In the 1960s, his depression deteriorated which reduced opportunities and he fell on hard times. Erich Pommer provided financial assistance and visited Andre when he could, but they no longer lived in the same city or even continent: Pommer had returned to Germany after the war, playing a crucial role in dismantling the Nazi film structure and rebuilding the West German film industry. Pommer died in Los Angeles in 1966.

Pommer’s passing hit Andre hard. He drifted around, living in a variety of cities in the U.S. and Europe, pursuing the occasional promise of employment or a romantic relationship.

Andre died in 1974. His body was found in a cheap hotel in Saint-Jean-de-Luz, a fishing port on the Basque coast of France. The coroner reported the cause of death was a self-administered overdose of barbiturates.

*

January 1973 – Harold

In court, Harold took to the stand.

“You are going to be shown an excerpt of a motion picture,” began the judge. “We’re not here to judge you on your right to make a film that many might consider obscene. Your role is solely to confirm that this film was indeed produced by yourself, and whether you recognize the women who features in it to be the same woman who appears in court today. Do you understand?”

“I do,” Harold replied, and the film began to roll.

*

The next part of ‘Harold Kovner – Rewind and Fast Forward’ will follow shortly.

*

Well – I *have* heard of Howard Kovner, and always wondered about him.

I am over the moon that you have deemed his life worthy of coverage….. and what a story!!!!! I can’t wait for thew second episode. Congratulations to all concerned 😉

What a nice history lesson.

Thank you Ron!

This a BREATHTAKING piece of research, and an amazing story.

I’m still trying to work out how this leads to XXX films so I am waiting for the next episode with baited breath.

Bring on the next installment!

We so appreciate that Charlie!

Well that was a surprise! Kovner is indeed one the enduring mysteries of early Gotham porn, but I never would have expected this. Excellent.

Thanks Big John!

Awesome Article Keep Up Good Work

Thank you Jeff!

So what name was credited for Mrs. Joyce Rosenzweig? Certainly not Cedar Houston, right?

All will be revealed in the final installment!

Another brilliant installment uncovering the tapestry of early adult cinema.

Thanks so much Sonny!

Could be just me but I feel you have enough material for a 300 page book here…

Really looking forward to part deux!

Thanks Albert!

Completely agree, Albert…

Feels like one of those splendid works of biographical fiction that you simply can’t put down. You have to force yourself not to turn to the last page. It’s almost a lost genre in literature today, but the Rialto Report continues to carry the torch, while DEEPLY delivering on any given Sunday. Sure beats Church!

Thanks as always Thelma!

Varian Fry was a HERO if the word means anything. Puts Hegseth and the like to shame. Not to mention old “bone spurs.”

Excuse my ignorance. What type of disc recording was available in the 1940’s? Are we talking audio? Records?

Thank you for such an interesting story. I read it in one sitting and look forward to the continuation!

You’re right, I had never heard the name Harold Kovner before…

Thank you for reading!

I hate nit pick, but the FADA 115 Bullet radio body was not plastic but Bakelite, a precursor of plastic. Otherwise a terrific account!