Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

I’ve always loved movies, especially the films I grew up with in the 1970s. I was seduced by their gritty realism, social commentary, complex characters, and a more honest portrayal of the human condition. And I was fan of that generation of film stars too: always surprising, sometimes conflicted figures, artists more than the celebrities that we have today. Movie genres seemed less important to me, so when I first saw Wade Nichols in an adult film on the big screen, it had just as big effect on me as, say, seeing Brando in ‘The Godfather’, De Niro in ‘Taxi Driver,’ or that fish thing in ‘Jaws.’

Ever since then, it feels that Wade Nichols has always been a part of my life, never far away from my thoughts. I’ve sometimes found myself wondering what it would’ve been like if Wade Nichol’s career had continued into the mainstream.

Wade Nichols is Indiana Jones in ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark,’ perhaps.

Or how about John McLane in ‘Die Hard.’

Mr. Miyagi in ‘The Karate Kid.’

Ok, scrub that last one. The point is that he captured my imagination in a way that was just as powerful as many of the recognized greats, and so I wondered about the possible twists and turns of his life that were prevented by his death.

Years ago, I turned my attention to finding who he really was, and perhaps also, why he’d remained important to me ever since my teenage years. That disproportionate impact of an early moment in your life that is instrumental in creating your adult sense of self.

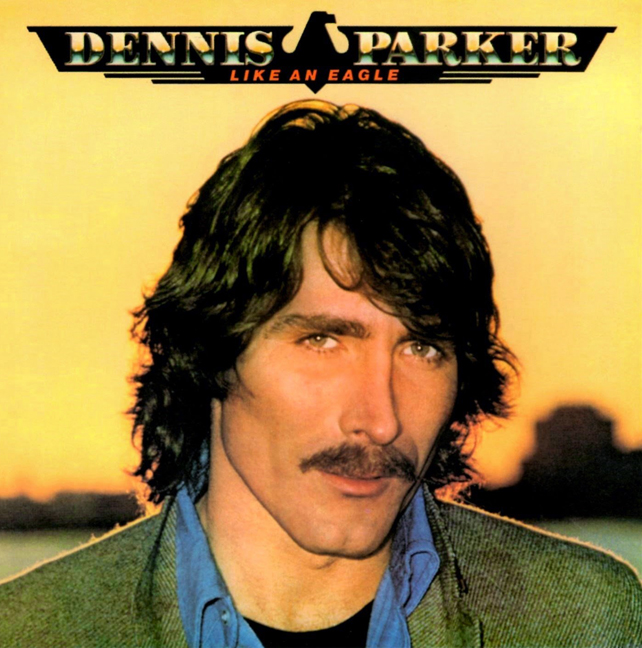

This is Wade Nichols: ‘Like An Eagle’ – His Untold Story. This is Part 2.

Parental Advisory Warning for those not familiar with The Rialto Report: this podcast episode contains disco music. This may be disturbing for younger listeners who may wish to switch off. As for the rest of you, clear a space on the dance floor and let’s get down.

This podcast is 42 minutes long.

————————————————————————————————————————————–

In 1975, Donna Summer was a little-known American singer who’d been living in Germany for eight years where she’d appeared in stage musicals. One day, she was playing around with a single lyric, ‘Love to Love You Baby,’ which she sang to an Italian musician and record producer, Giorgio Moroder. He liked the hook, and came back a few days later, having turned it into a three-minute disco song. He suggested to Donna they record it together. She wasn’t sure about the idea, mainly because the whole thing that Giorgio had come up with just sounded so damn sexual. In the end, she agreed to sing it as a demo which they could give to someone else. So she did, but the trouble was that her erotic moans and groans so impressed everyone who heard it that, they decided to release it as a Donna Summer single anyway, and ‘Love to Love You’ went on to become a small-time hit in Europe.

Fast forward a few weeks, and a tape of the song found its way to Neil Bogart, who was the president of Casablanca Records in the U.S. He listened, liked it, and decided to play it at a party at his home the same night. Next day, Bogart got Moroder on the phone. There was a problem with the song, he said: at the party, he’d started playing the song and approached a girl, but by the time he’d started speaking to her, the three-minute single had come to an end. So he had to run back to the tape deck, rewind it, and start playing it again before resuming his pick-up lines with the girl. Just as he got to the stage of propositioning her, the damn song ended again. Same drill: rewind the tape, and start it over again. A few minutes later, he was at the point of asking the girl to join him in the bedroom when, you guessed it, the song finished once more. So, as Bogart protested to Moroder, “How is this meant to work?”

Giorgio threw the question back to him: “How long do you need to meet a girl, chat her up, seal the deal, take her to the boudoir, and do the deed?” he asked.

Bogart paused, doing the sexual math in his head: “I reckon sixteen minutes should be enough,” he said.

And so, sure enough, Moroder and Donna Summer made a recording of the song that lasted just over 16 minutes, and released that version in the U.S. In fact, it took up the entire first side of the album of the same name. But it worked, and the single hit number one on the Dance chart and became one of the great disco songs of all time. I once read that a group of scientists estimated than 1.5 million babies had been conceived to that 16-minute record.

The time was right for music and explicit sex to be combined. And so who was better placed to take advantage than Dennis Parker?

*

1976

Let’s go back to 1976. They say when a man makes plans, God laughs. Certainly, Dennis’ life was nothing like he’d planned, but he had few complaints.

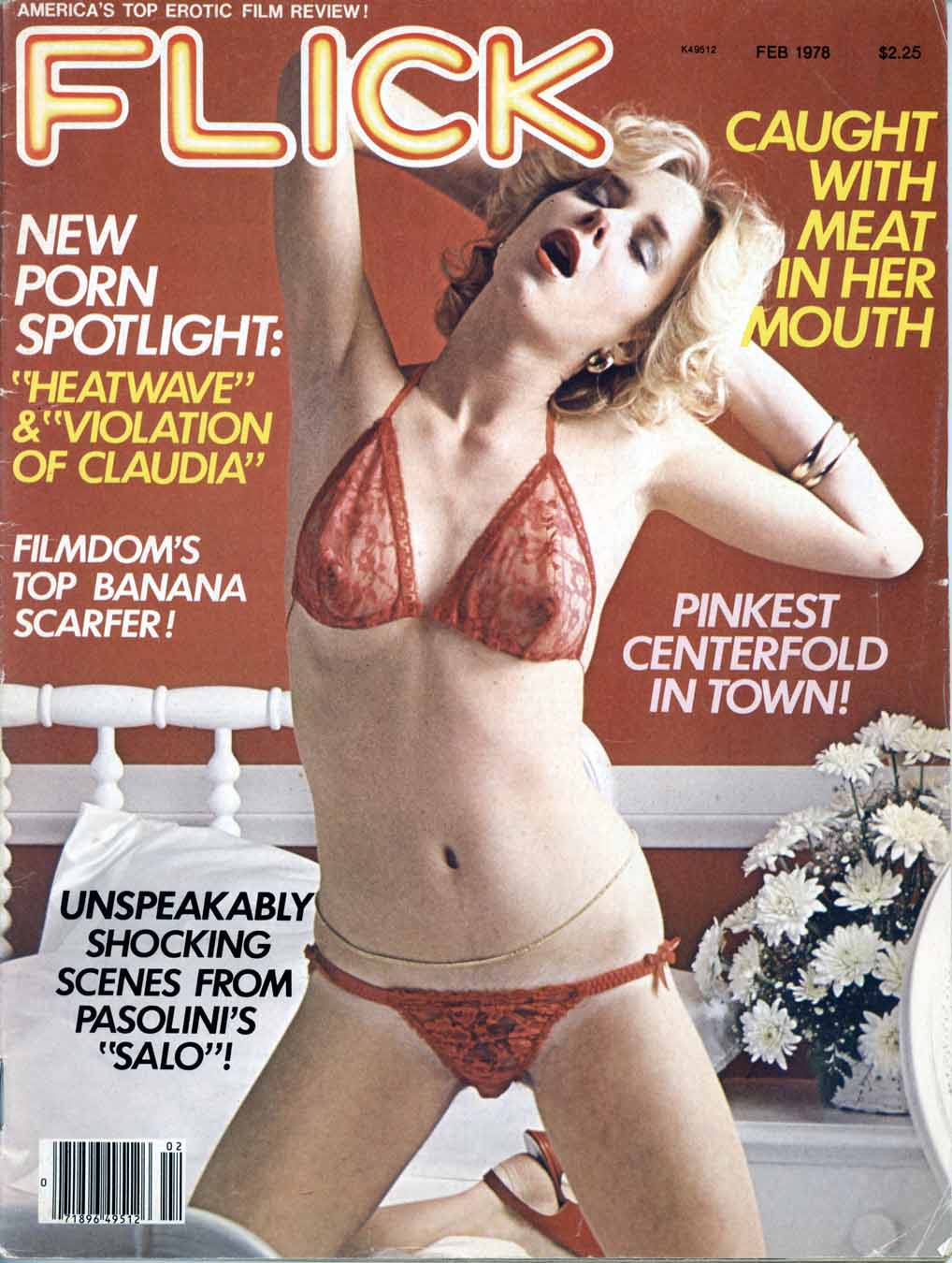

For a start, he was now a movie star, adored and lusted over by men and women, earning reasonable money for his screen appearances in X-rated movies, and regularly interviewed in magazines who fawned over his acting talent, not to mention his smooth 1970s good looks. Every couple of months, Dennis would get a call from someone on the adult film scene offering him another porn job. He’d always happily accept, turn up and do the business – which usually meant reciting lines with casual, effortless cool, having sex with the latest starlet, and then leaving with a few hundred dollars cash in hand. Most porn film jobs took a matter of hours, usually over a day or two, though sometimes there’d be an ambitious project where an aspiring sex-film Francis Ford Coppola wannabe had raised enough money to make a movie they were convinced would be the mythical mainstream cross-over success. Films like ‘Blonde Ambition,’ ‘Punk Rock,’ ‘Honeymoon Haven,’ and ‘Maraschino Cherry’ came and went with Dennis calmly enhancing them all and impressing fellow performers and fans alike.

By now, he’d jacked in his office day job, which meant that he had more time to devote to his art, carpentry, motorbike, jazz record collection, and his partner, a young actor/model, Joey Phipps, who he adored and doted on. They lived a quiet life in Dennis’ tiny apartment, punctuated by wild nights out in Manhattan sex clubs.

Ah the gay clubs of the 70s: Dennis came out when he was in college and spent the next decade in New York’s darkest, horniest and most outrageous corners. Their names are all you need to know. The Eagles Nest, the Anvil, the Ramrod, and the Toilet. It was the era of poppers, gloryholes, and anonymous hook-ups in sweaty backrooms. As if that wasn’t enough, Dennis also had a sideline as a male escort for wealthy clients who responded to his weekly ad for personal services. It was extra cash, and his friends told me about how he enjoyed meeting different people and making them happy.

In short, Dennis’ was a normal life in which almost everything was abnormal. And then it all changed. He met a Frenchman, a music producer who’d recently moved to New York and was starting to enjoy huge international success writing and producing disco hits. He had an impish, youthful face with a chipmunk smile. His name was Jacques Morali.

*

The Birth of Disco

Jacques Morali was born in 1947, the year before Dennis, in Casablanca, French Morocco, to a Moroccan Jewish family. According to legend, he had a fiercely protective upbringing, and there are stories that he was dressed as a girl by his mother when he was growing up. When he was 13, his family moved to France, where Jacques became a musical prodigy, gifted at playing different instruments, and writing songs in any style. He wasn’t afraid to be different: he was original, flamboyant, and gay. He was also outgoing, outrageous, and gregarious, and seemed to know everyone on the music scene in Paris. By the end of the 1960s, he was in demand, writing music for orchestras, for the Crazy Horse cabaret and strip club, and for himself in his bid to launch a career as a solo artist. And because of his knack for writing instant melodies, he was also writing and producing songs for others. An example Is an early single, a long-forgotten song called ‘Viva Zapata’ for a long-forgotten artist called ‘Clint Farwood’ which gives you an example of the hallmarks of his developing style. Upbeat, check. Cheesy, check. Annoyingly catchy, you bet.

But Jacques, just like his music, was restless and always changing, and he was constantly looking for the next big idea. He was also impatient, demanding, and dissatisfied with the level of his success in France, so he started to look to America as being where he could really hit the big time. In the early 1970s, he discovered the music that was coming out of a studio in Philadelphia called Sigma Sound where the Philadelphia International Records label were recording a streak of hit singles. Songs like the O’Jays’ ‘Love Train,’ recorded at Sigma Sound, which hit number one in 1972.

As strange as it sounds, Jacques Morali wasn’t the only prominent music producer and songwriter in Paris at the time who came from a Moroccan Jewish family in Casablanca, Morocco – and the other one was Henri Belolo. Given their similar backgrounds, it was natural they gravitated to each other.

Henri was ten years older than Jacques: he was also a talented musician, but he differed in that he was also a highly successful entrepreneur: Henri had already set up his own record label and music publishing company, imported and promoted records into France, as well as organized concerts in Paris by the likes of James Brown and the Bee Gees. And, just like Jacques, Henri was eyeing the music scene in America.

In 1973, Henri traveled to New York and set up a record company called Can’t Stop Productions to establish a presence in the U.S. music market. During his trip, he went down to Philadelphia to see friends, and that’s where he discovered the same music scene that Jacques had fallen in love with. I met and spoke to Henri Belolo several times over the years, and his excitement for that music still shone decades later. As he told me: “I started to listen to this ‘Philly Sound.’ I became friends with the owner of Sigma Sound, which was the famous recording studio where all of the Philly people were recording, and I got acquainted with musicians and arrangers and the music that came out of Philadelphia International Records.” In particular, Henri loved ‘TSOP (The Sound of Philadelphia)’ by The Three Degrees.

The song was released in 1974 as the theme for the American musical television program ‘Soul Train,’ and it was the first television theme song to reach No. 1. Henri told me that the song and the visuals of the TV show changed his life: “I suddenly knew that the next generation of music stars would be more beautiful to look at,” he said, “and that these new artists would be more physical and sexual.” Henri was so impressed with the city that he set up a talent scout office in Philadelphia. As he told me, “I returned to France a different man. I promised myself that I would come back to America, and Philadelphia, when I found THE idea. I just needed to find something unique and big and hot.”

So here you have two Moroccan Jews, one gay and one straight, both based in Paris, both ambitious, and talented musically, both enamored by the music coming out of Sigma Studio in Philadelphia, and both looking for ways to break into the American music scene. Back in France, Henri says Jacques started turning up at his office to offer his services: “He was so enthusiastic,” Henri remembered, “Jacques dreamt of going to America, so he was pitching new ideas to me every week.” In the end, Henri told Jacques that if he came up with one really good idea, then he’d take him to America – but it had to be a really special idea, because nothing that Jacques had suggested so far had convinced him.

Then in 1975, a breakthrough. Jacques went to see Henri and told him his latest idea: he’d found an old Carmen Miranda song, ‘Brazil’, that he wanted a group of larger-than-life females to sing, and record it with production values that would turn it into an epic record for the clubs. It was a crazy idea, but Henri liked the concept: “You have to remember the word ‘disco’ didn’t really exist at that stage,” he remembered. “But I loved the idea of making a big club record: it captured my imagination, so I agreed to work on it with Jacques.”

Not only did he like the idea, Henri agreed to finance a residency for Jacques at Sigma Sound Studios in Philadelphia, the very home of the music they both loved. The two of them flew out to Philadelphia and within two weeks they’d found three beautiful black women who they named The Ritchie Family, even though the singers were entirely unrelated to each other, and then Jacques hired the best strings and horns from the elite pool of Philly Sound musicians.

The single ‘Brazil’ was released in July 1975, and it was the U.S. hit that Jacques and Henri wanted: it peaked at No. 11 on the Hot 100, became a worldwide success, and Billboard were so impressed they created a separate Disco chart for the first time: Brazil hit No. 1 on that chart too.

The record convinced Jacques and Henri they should continue to work together, and so they both moved over to the U.S., and became long-term musical partners and a virtual disco-hit factory. Belolo would write the lyrics and handle the business side, and Jacques provided the hook-driven, dance music. More success came quickly with No. 1 disco hits, such as ‘The Best Disco In Town’ (1976)

Jacques’ music was characterized by simple arrangements, a unique sense of camp, and simple catchy melodies that could be remembered easily. It wasn’t rocket science, but it didn’t need to be – few others could do it as well as him. In the next eight years between 1974 and 1982, he recorded over 65 albums, for artists as diverse as Cher, Dalida, and Pia Zadora.

Henri and Jacques were on top of the world, splitting their time between New York and Philadelphia. Henri remembered that if they weren’t producing music, they were partying: “We were going every night of the week to every club in town,” he told me. “That included the straight and gay clubs – Jacques was gay, I was not – but we had a lot of gay friends, and I was always keen to know what they listened to. I would dance until the early hours, and then go home and get some sleep. But Jacques would party all night – and it was on one of those nights when he met Dennis.”

*

Dennis meets Jacques

There is some mystery surrounding how Dennis first met Jacques.

Some friends, including Dennis’ brother Richard, thought that it must have been at a bar or a disco. Could be, though it seems less likely to me as Dennis didn’t spend a lot of his time in discos, and the bars he frequented tended to be ones that were more interested in sex than music. According to others, they met through the ad that Dennis ran in the weekly newspapers. “That was what Dennis told me,” said a friend called Chip that I spoke to. “He told me that Jacques was lonely, or horny, one weekend, and came across Dennis’s ad offering company.”

What is known is that when they met in 1977, Jacques instantly fell head over heels in love with Dennis. As Henri Belolo remembered: “Jacques told me straight away that he’d met this sexy and handsome guy that he was madly attracted to. He always said he loved a good-looking mustache! So obviously, Dennis fit that description.” Chip concurred: “Jacques was completely besotted by Dennis, it was obvious for everyone to see. His world suddenly revolved around Dennis.”

And so, while Jacques’ music career in America was taking off and he was becoming a household name in the music world, he and Dennis started a romantic and physical relationship. It was a fascinating union: on the one side, a flamboyant, big-time disco music producer, and on the other, a quiet jazz-loving porn star with a sideline doing escort work.

There are many aspects that intrigue me here: firstly, there was the fact that Dennis was still starring in adult films when he met Jacques – and continued doing so after they met. But far from being a problem for their relationship, Jacques was intrigued by the emerging and sexual world of XXX, and he enjoyed Dennis’ stature as a sex star. As Henri told me, “Jacques was excited by the fact that Dennis was a porn star… not only in gay movies but in straight movies too. It just increased the allure that Dennis had in Jacques eyes. It was a challenge for him to have an affair with a porn star like Dennis.”

And in the free love, anything-goes, no-judgement world of the New York club scene in the mid 1970s, Dennis’ porn films posed no risk to Jacques’ career – if anything, Dennis’ sexual standing was an asset to Jacques.

But if Dennis was perfect for Jacques, was the reverse true? What did Dennis find attractive in Jacques?

Tip Sanderson, a friend of Dennis at the time, reckoned that it was the showbiz allure that was the appeal for Dennis. “What Jacques had in his favor was the music business,” Tip says. “The glitz, the scene, the money… and he exploited it to the max. He told Dennis he would make him a star, a big music star. Dennis was seduced by that. I mean, who wouldn’t be?”

But was it love between Jacques and Dennis? Friends are still skeptical. Tip Sanderson said this: “Jacques was clearly infatuated with Dennis. Totally in love with him. It was sheer physical attraction. But Jacques wasn’t Dennis’ physical type at all, so perhaps the attraction wasn’t as… mutual.”

Henri Belolo agreed saying, “Jacques was in love with Dennis, but I don’t know about Dennis. It’s hard to know, but I doubt it. Was Dennis really attracted to Jacques? I don’t think it was mutual. But the fact that Jacques was a successful music producer definitely helped their relationship.”

Which brings me to another question. What happened to Joey Phipps in all this, Dennis’ partner who he’d been close to and living with for a while? That was a problem, everyone admitted to me. Most said that Dennis was still in love with Joey.

As Tip Sanderson told me: “It was sad because they were tight. In the end, Dennis chose Jacques over Joey. Maybe the allure of fame was more powerful than his feelings for Joey. Either way, Dennis moved in with Jacques.”

So Jacques and Dennis became a couple, with Dennis leaving Joey behind in his tiny, beloved apartment, and he moved in with Jacques, a few blocks away, in his luxury, extensive suite at The Bristol, a prestigious uptown New York address in the Sutton Place neighborhood.

For some reason, I’m reminded of the Terrence Malick period drama film, ‘Days of Heaven’. It came out around the same time that all this was going on. The comparison is imperfect, sure, but if you haven’t seen the movie, the plot involves an impoverished couple, played by Richard Gere and Brooke Adams. Their life is a struggle though they are essentially happy – but then Gere’s character encourages his girlfriend to marry a wealthy grain farmer, played by Sam Shepherd. The reason is the financial security that this will bring. So she leaves Gere, and he’s left living in their small sharecropper property looking up the hill at the mansion into which she’s moved. There’s a heartbreaking element of poignancy and sadness to their separation, and a reminder that not all stories of true love have a happy ending. Did Dennis get what he wanted but lost what he had? Did his new lifestyle come at the cost of love?

It certainly was a step up in terms of lifestyle: being an adult film star had given Dennis’ life an occasional glamor, but this paled in comparison to what he experienced with Jacques. Richard Posa, Dennis’ brother, remembers Dennis telling him that Jacques was making around $8 million a year – and this was back in the 1970s. Jacques was generous with his money, and Dennis’ lifestyle changed overnight. For Dennis, the days of the dark and moody gay leather clubs were over. It was now fancy discos like Studio 54, The Loft, and the Paradise Garage.

Steven Gaines, a friend of them both, told me about visiting their apartment: “Jacques gave me a tour. He took me to the bedroom which was really over the top, and everything in it was super-expensive. There was this beautiful suede headboard – and Jacques said in a thick French accent, “Zees ees where I fist fuck my boyfriend.” I don’t know what I was thinking, but I said, “But what about that suede headboard… aren’t you afraid of ruining it?” Jacques looked horrified, and said, “Whaaat? Do you think we’re peeegs?!’” Which reminded Steven of a joke that he told me: “How do you make a gay man scream during sex? You wipe your hands on the drapes.”

Henri Belolo, Jacques’s music business partner, was living around the corner from Jacques and Dennis, and they would all hang out regularly. As Henri remembered: “I was great friends with Dennis, and I liked him a lot. We had dinner regularly. And my wife liked him because he was a good guy, very soft-spoken, well mannered, and elegant. In many respects, Dennis was the opposite to Jacques. Jacques was loud and extravagant, and Dennis was quiet and reserved. I’m sure that Jacques drove Dennis crazy a lot of the time.”

*

The Village People

There are two stories about the how the idea for the Village People first came about.

Jacques’ version was that he went to a costume ball at Les Mouches, a gay disco in Greenwich Village, way over on 11th Street on the west side. He was so impressed by all the costumes and the macho male characters portrayed by the party guests, that the idea came to him to put together a group of singers and dancers, each one playing a different gay fantasy figure.

Henri Belolo remembers it differently, saying that he and Jacques were walking through the Village one day, when they saw a man in a native American Indian outfit walking down the street, complete with bells attached to his feet. They followed him into a bar where he danced on the tables – watched by a cowboy and construction worker. According to Henri, “Jacques and I looked at each other and suddenly had the same idea. We said “My God, these characters. They represent the different types of the American man. We need to start a music group like this!”

Whichever story you believe, they took the concept and started work on a single, and signed a licensing deal with Casablanca Records, one of the most famous disco labels – and founded by Neil Bogart, the same Bogart who had requested the 16-minute version of ‘Love to Love You, Baby.’ The label was already prestigious because of acts like Kiss and Donna Summer, but according to Henri, he and Jacques were most excited just because of the name, given that they’d both been born in Casablanca. They decided to name the new group ‘The Village People’ because the idea came from the characters they’d seen in the Village, and the first single was ‘San Francisco (You’ve Got Me).’

The irony was that when the single came out, the group just consisted of one singer, a Broadway star called Victor Willis, who was appearing in the Broadway production of ‘The Wiz’ at the time, and they dressed him up as a cop.

Sales of the single soared, and so, as Henri told me, “We said to each other, ‘We’d better put together a real group now’ because we’d signed up to an album with Casablanca Records.” They set about assembling a group of five males, each one having his own distinctive character. To do this they took out an ad in a theatre trade paper which read: “Macho Types Wanted: Must Dance And Have A Moustache.”

And who fit that bill better than Dennis?

Henri told me that Jacques had been looking for an opportunity to give Dennis a starring music opportunity ever since they had first met: he told me, “To be honest, every time Jacques met someone, he’d say, “I will make of you a star, my dear” with his big French accent. And Dennis was no exception. Except of course, Jacques was in love with him. So this time, Jacques was really serious about it.” Dennis’ brother Richard remembered the same: “When Jacques was putting the Village People together, he offered Dennis a role in the group.”

It’s intriguing to imagine Dennis as a member of the Village People. Would he have assumed one of the character identities that ended up in the group, or would he have developed a different identity of his own?

Somewhere along the line however, the idea was dropped in favor of making Dennis a star in his own right. As Dennis’ friend Tip Sanderson said to me: “Dennis said that he and Jacques decided that they would not make him part of the Village People – where he would be only one of five members of a group, but rather they’d hold him back and launch him as a solo star instead. And so, the two of them carefully mapped out a plan to create a music career for Dennis.”

Meanwhile the rest of the members of the Village People were hired – representing stereotypes such as a leather man, cowboy, construction worker, and native American. They were largely recruited for their look rather musical abilities, with Victor Willis, taking all the main vocal duties. Together they became one of the most successful acts of the disco era with hits such as ‘YMCA’ (1978), ‘Macho Man’ (1978), ‘In the Navy’ (1979), and ‘Go West’ (1980).

Their success only increased Jacques Morali’s reputation as a top disco producer and star maker.

*

Dennis Parker – Disco Star

I was intrigued by the decision to give Dennis a solo singing career. I wondered what Dennis thought of the idea. Was he just as excited by it, or did he go along with it because of Jacques’ ambition and exhilaration?

On the one hand, Dennis’ ex-boyfriend Skip had told me that Dennis always wanted to be a torch singer, and so this was an opportunity to be produced by one of the hottest disco producers in the land. Dennis did love performing and though this wasn’t acting on a theater stage, it was still about embodying a character.

But then there was another side to it: Dennis was a private person, happiest when doing carpentry, driving on his motorbike, and listening to his jazz records. How did he feel about making himself a more public figure?

And then there was the type of music Dennis would be singing. Tip Sanderson saw this contradiction too: “Dennis wasn’t a big pop or disco music fan,” Tip said. “So he had a few reservations about the idea of a solo dance music career. But Jacques was so enthusiastic that I guess Dennis was caught up in the excitement.”

Whatever doubts existed however, Dennis signed up and went along with Jacques’ vision of making him a disco star – and the first step was a significant one. These are the words of Skip St. James, Dennis’ former partner from the early 1970s: “I saw Dennis on and off after our relationship ended. I knew he’d been dating Jacques Morali. Then at one point, Dennis disappeared completely for a short while. When he re-appeared, he said he’d been in Philadelphia. I was struck by the change in his appearance. He had new teeth and a new nose! His old nose was a handsome Roman one, and when he came back he had a turned-up nose that he said was modeled after mine. I didn’t like his nose because I adored his old one. To be honest, I think he was better looking before the nose and teeth work.”

It was true, when Dennis started to be groomed by Jacques for disco stardom, his appearance changed noticeably: his cheekbones, nose, and chin were now leaner, sharper, and more pronounced than the way he looked in the films and the photo features. He looked great, just rather different than the adult film star, and completely different from the nerdy school kid in the pictures that his brother Richard had sent me.

The second change that Dennis made was that he stopped making X-rated films. Unlike many ex-adult film stars who leave the business and immediately disavow their sex film past, Dennis never did. The sex films were not something he ever regretted or denied. But his retirement from the adult business was the only sensible course of action if he was going to make a serious bid for stardom in mainstream America. It wasn’t a difficult choice: he was in his thirties, he’d already appeared in over 30 sex films, he didn’t need the money, and according to his friends he felt it was time for a change anyway. One of the last events of his sex movie career was that Screw magazine voted him ‘Man of the Year’ in 1978. Dennis got a kick out of that, and bought copies for all his friends.

So now Dennis looked the part, and had a superstar producer in Jacques in his corner, but what about the singing part of this career change. After all, his singing activity hadn’t consisted of much more than humming along to his jazz records, so recording a whole album was going to be a completely new experience for him.

One of the skeptics was Henri Belolo. Henri told me about the day he first learned of the idea: “Jacques said to me, ‘We’re going to make an album with Dennis.’ I told him, ‘But Jacques, we can’t. He’s not a singer!’ Jacques said, ‘I know. He’s an actor, but he’s good looking and believe me, we can make him a star. Trust me.’” Jacques’ argument was that they’d already turned several non-singers into the Village People – so why not Dennis? So together they agreed to produce an album for Dennis.

Not that Jacques went easy on Dennis: Henri told me that Jacques made Dennis work hard. He got Dennis to take singing lessons, practice night and day, and prepare intensively. And then in 1978, Jacques secured a record deal for Dennis with Casablanca Records, and so the record idea suddenly became real.

Henri and Jacques snapped into action and started to assemble a selection of songs. Henri described how they split the work: “Jacques and I had different roles,” he told me. “Jacques was the melodist. He was a magician with all the hooks and the melodies. I was the one that came up with the ideas for the lyrics. But my English was not too good at that time, so I started to write the song in French or in bad English and then I got help.” One of the people he turned to for lyrics for Dennis’ record was Steven Gaines, a journalist who’d just written an article about how the Village People had been formed. Gaines told me, “I wrote about how Jacques was selling the Village People like a sports team with different characters and personalities. And now, he was going on to ‘invent’ somebody else – and that was Dennis.”

Jacques loved the write-up, so he called Gaines up and suggested that he write the lyrics for Dennis’ album. Gaines recalled that a few days later, Jacques sent him click tracks to work with. The click tracks were just audio clicks to show the rhythm of the song… nothing else. But he gave it a shot, and came up with the lyrics for ‘Like an Eagle’.”

Gaines recalled Jacques’ reaction to that song: “When Jacques heard it, he said that the words were too complicated for people to listen to on a dance floor. I’d done a lot of work on them, and believe me, they weren’t that complicated! Jacques said he would work on them. He did – and in the end, the lyrics were as follows…: ‘Like an Eagle, Like an Eagle, Like an Eagle, Like an Eagle, Like an Eagle, always searching, always wanting, Like an Eagle.’ So, he certainly made them much less complicated…”

When the songs were ready, Jacques and Henri assembled many of the musicians that had played on their favorite records that came out of Philly, including the same rhythm section that featured on the Village People records. Also notable is that they decided to use synthesizers instead of strings, which was new for the time. When everything was ready they booked, where else?, the Sigma Sound studios – but not the original location in Philadelphia.

In 1977, a second Sigma Sound studio had opened in New York City. It was located in the Ed Sullivan Theater building – that’s the same building where David Letterman’s and Stephen Colbert’s Late Show is filmed each night. This studio was used by the Village People for their records, and would later be used by singers and groups like Madonna, the Talking Heads, Rick James, Aretha Franklin, the Ramones, Whitney Houston, Paul Simon and others.

The whole endeavor was now a big deal, and Dennis was at the heart of it all. How did he cope with the pressure, in that environment, in that recording studio? He was surrounded by professional musicians of the highest quality, used to recording with many of the great vocalists of the time. Was he overawed, out of his depth, and did he struggle? I contacted many of the musicians who recorded with Dennis to find out their memories of making the record.

Alfonso Carey was the first I spoke to. He was the bass player that played on all the Village People hits… from ‘YMCA’ to ‘Macho Man’ and the rest, as well as records by The Ritchie Family and Patti Labelle. In fact, he also wrote the song ‘Why Don’t You Boogie’ for Dennis which was included on the record.

Carey’s first memory was that he found Jacques flamboyant: “Jacques was very ‘out there,’ “Carey told me. “He would let you know in a minute that he was wonderful and gay. He brought Dennis into the studio, and Dennis was completely different. We thought he was cool, and much more chill than Jacques.” I asked Carey about Dennis’ vocal ability. He said that Dennis had talent, not like Victor Willis of the Village People with a voice that could really move you, but he was somebody who could hold a note and that he did all right.

Henri Belolo also remembered being impressed with Dennis: “Dennis voice was actually pretty good!” he told me. “We had to work around it at times, for example, Jacques sang certain passages at the same time as Dennis to augment Dennis’ vocals. So on ‘Like an Eagle’ when you hear the high voice sing just after the chorus, that’s mainly Jacques singing. We also used background singers to cover up some parts as well. But I have to say, honestly, Dennis did his part, and did a great singing job for someone who had no experience.”

Phil Hurtt was Dennis vocal coach and he also wrote two songs for Dennis’ album: ‘I’m A Dancer’ and ‘I Need Your Love’. Hurtt told me that when Dennis recorded the album, the musicians were actually not there most of the time. That was normal. They’d already recorded the basic tracks by then. So when Dennis was in the studio, he was just there with Jacques and Henri, the engineers, and Phil himself. “I was the only one actually in the recording booth with Dennis because I was teaching him the vocals. I stood alongside him until he got it. That was what I always did.” Phil Hurtt was keen to point out that Dennis had a better voice than you hear on the record. “I think he was misused,” Phil said. “I think if he had been working with a producer who knew how to produce different types of music then he would have done even better. He was a nice guy though. Quiet and polite.”

The other song that Gaines wrote for Dennis was ‘New York By Night.’

This is how Gaines remembers writing it: “I wanted to write something that was contemporary about New York, and so I included details like the hustlers on 53rd St.

Henri told me: “The lyrics of ‘New York By Night’ are fantastic. One of my favorite lines goes – ‘At Studio 54, they’re waiting at the door, Can’t get in, just can’t win.’ It captures the moment when we went to Studio 54 every night. We were in the middle of the disco revolution. It was crazy, my God, but so much life, so much happiness, so much enjoyment. We weren’t fighting a war, the economy wasn’t too bad, and people wanted to go out after Vietnam. They wanted to have a good time. Sex was starting to get liberated, the gays were starting to come out. Everything was exploding, it was a new generation, and of course they did not want to be the old generation that was pop or rock – they wanted to be disco. That’s what it was.”

Once again, Jacques said it was too complicated. He wanted me to dumb it down because he said that Dennis couldn’t sing so many words that quickly.”

But this time, Jacques was overruled, both by Dennis, who insisted that he could handle the words, and Henri Belolo – who loved the lyrics.

Whoever I spoke to, everyone always seemed to come back to Dennis’ personal qualities. He was gentle, kind, and considerate. Carla Bandini-Lory, the record’s Assistant Producer told me: “Dennis was a sweetheart, and he impressed everyone. He was a gentleman, he held open doors, never acted above the support staff – which many other people at that time did. He was a total pro. He listened, he took direction from Jacques, and he understood what was going on. Even so, he was always in Jacques’ shadow. Everyone was in Jacques’ shadow. Jacques was always the biggest personality in every room.”

Steven Gaines, the writer of ‘Like an Eagle’ and ‘New York By Night’, went to the studio and to watched them record his songs, and his memory was similar: “Dennis was very cool, and very low key. I don’t remember a big ego or personality thing about him at all. Jacques was a French queen, quite the opposite… a big flamboyant character. When Jacques was good, he was very, very good, but when he got mean, he was really horrid.”

Henri Belolo agreed, and admitted that sometimes Jacques would blow up. Henri said: “During the recording sessions, Jacques got upset and frustrated with Dennis. Jacques could be rude with him. I kept telling Jacques, ‘Relax. Dennis is not a professional singer. You must be patient with him, he’s doing his best. It was your idea to do this album with Dennis, so now you have to learn to work with him. The final result will be good.’ But what amazed me was that Dennis was very calm even when Jacques was angry. Dennis was always calm. I never saw him excited or shouting or mad. He was a pleasure.”

Henri was the Executive Producer for the record, so had overall creative control of the record, and he told me he was happy how it turned out. Neil Bogart, the head of Casablanca Records, liked it as well and was excited to release it. Dennis adopted the name ‘Dennis Parker’ to distance himself from Wade Nichols and his previous career as a sex film star.

The last step was a photo session of Dennis in New York at night for the record sleeve. Let’s spend a moment on that LP cover, as it’s magnificent. If you haven’t seen, try googling it. It features Dennis at his zenith, all cheekbones, moustache, a hint of a dimple in his sculpted chin, and casually tousled yet carefully curated shoulder-length hair, dressed in a denim shirt and a gray sports jacket. Somehow looking coy, mistrustful and confident at the same time. He knows a secret that he might just share with you… if you’re good to him, that is. I’d pick this picture for my mantelpiece over the Mona Lisa any day of the week.

So everything was in place, but how would the disco crowd react? After all, no one had even heard the record yet.

Steven Gaines remembers that, just before ‘Like an Eagle’ came out as a single, Jacques got a disc jockey to play it at a gay club called the Flamingo one night. The Flamingo was a calculated choice: the club had opened in 1974, and was New York’s first exclusively gay disco. It was located in an upstairs loft space on the second floor of a building at the corner of Houston and Broadway. The club was actually secret and had an unlisted telephone number because there was a constant fear of police raids. And it was exclusive too: members paid up to six hundred dollars a year for a membership. It was known for its wild parties, there were stories of a Crucifixion night with models dressed as Roman legionaries and a Jesus Christ who would, from time to time, turn his eyes heavenward and ascend a cross. This was the crowd that would be the first in the world to hear Dennis Parker.

Gaines, understandably, decided he wanted to see his song unveiled publicly for the first time – especially to this audience, so he went along with his lawyer. As he told me, “It was a big dance place, and an important place to launch a record. There were 1,500 gay guys with their shirts off, completely stoned on ethyl chloride. Then the song came on for the first time, and it was really, really thrilling.

“People didn’t know it obviously, and it starts with that whooshing sound before building up.

“I’ll never forget how exciting that moment was… it just really, really worked well… at least until my not-so-brilliant lyrics started. It got a great reaction, the crowd really loved it.”

When the song came to an end, the Flamingo club members demanded that it was played again. And then again, even chanting the title lyrics over and over.

For the second time in his life, quiet, unassuming Dennis had become a star again.

*

Wonderful investigative reports on the late Dennis Parker and in my case, no need for any warnings before I listened to it, since I´m an enormous fan of Disco Music (au contraire, actually).

My fave tune by Dennis is ” I´m a Dancer ” which I monickered ´The best Village People song that did not showcase-at least officially-, said group (the song´s lyrcs, basically defined the widespredreach of the 70s Disco movement and how democratic it was, gaining admirers from all walks of life during its heyday, with a portion going ” See that guy on the floor

He! – Brings the mail to your door

She! – Is a clerk in a store

You! – Need a change in routine

So! – Put yourself on the scene,,,”

Just unbelievably catchy stuff…thanks forthe kick-ass job, Ashley!

Thank you MASF!

Thanks for the article, April!

Awesome Article And Podcast Keep Up Good Work

Appreciate it Jeff!

I’m 100% in agreement with Marco…

Mr. West’s stern “Anti-Disco” warning didn’t dissuade me in the slightest. Instead, I cranked up the volume as I was winding my way down coastal California, savoring every legendary song, along with Dennis’s quiet perseverance and dedication. It’s clealy apparent that Dennis was never attempting to “reinvent” himself…

Instead, Dennis/Wade charismatically (but gently) placed himself on a dendritically defined stage mark. Thank you Rialto Report for such an exquisitely, well-told story. I can only imagine that Dennis’s particles continue to ignite the lives of others attempting similar pathways. Sound track was absolutely over the top.

– Thelma

Thank you so much Thelma!

Thanks, Thelma.

Looking forward to part 3. Check out this promo video Dennis made for Like an Eagle. Fascinating! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ujbSkWKTuHo

Oops and another one! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TN0hlI3zizM This may have been what was shown on the Merv Griffin Show.

And more. Wade’s scene in the mainstream film Monique (1978) where he sings – you guessed it – Like and Eagle. The hit just keeps on coming! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cEV-d2gtr3M

OK, ok, one more. This is a mystery. Clip from a movie with Dennis’s song I Need Your Love. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aCK-0xLp6NQ Any help on what movie this is from?

Hi Ledhed: The clip seems to come from the 1977 film VISIONS, directed by Chuck Vincent and featuring Roberta Findlay (using a pseudonym) as cinematographer, Sharon Mitchell as a “trapeze girl” and adult actor David Christopher (as one on the burglars on the scene where Dennis’ character is attacked). If you read the one posted review (by “lor”) for this film on IMDB, you’ll see his description of the plot corresponds with the scene posted on YouTube. By the way, I think the Dennis Parker song “I Need Your Love” was spliced in (as a tribute?) and that the film probably has different music during that scene.

Thanks, Javier. Yes I found the full film. The youtube clip starts with the very first scene in the film. And you’re right. I Need Your Love – inserted as Wade’s character is attacked – is not in the film. The clip is pretty much all of Wade’s non-explicit footage from the film; all that can be shown on youtube ofc! Sharon Mitchell is amazing! Early years of her career. Thanks for the help. Great find!

Your Dennis/Wade story coverage is one of the greatest achievements of TRR and deserves to be heard by the entire world. A documentary, feature film, book etc. Bravo!

Appreciate that Mike!

“Like An Eagle” is easily one of the best lp’s of the late 1970’s. It still holds after many listenings.

Simply amazing, jaw-dropping research. I cannot wait for the next chapter and to find out how Dennis segues from disco phenomenon to soap opera star.

I still have his original LP! Probably played that LP a hundred times. Thank you Rialto Report for telling these stories and creating these time capsules for future generations to discover.

The best song on the album, in my opinion, is High Life which is a song that pretty much sums up late-70s New York Disco night life. The whole album is surprisingly good. I recall the album being released in 79 when the Disco backlash started happening. Maybe if the album was released say early 78 he would have had better chart success. Disco was everywhere up until fall 1979 when it waned

Dennis might have been more confident to audition for Edge of Night because he’d also auditioned and gotten a couple of speaking roles in television commercials in 1979, such as this one:

https://www.instagram.com/p/CW-qKIzrDbC/

Don Keller! hahaha Great post, George! thx.

Wonderful retrospective and documentary. Is a part three coming? Thank you

Loved the music!!!! So fun! I’ll have to play something from his album on my show sometime! I’m excited there’s a part 3!